Glastonbury 2023 has gone down in the festival’s history as the inaugural year of the Woodsies stage, the 10th anniversary of its official newspaper, and the site of Elton John’s final UK gig, which closed the festival with an extended rendition of Rocket Man set to fireworks.

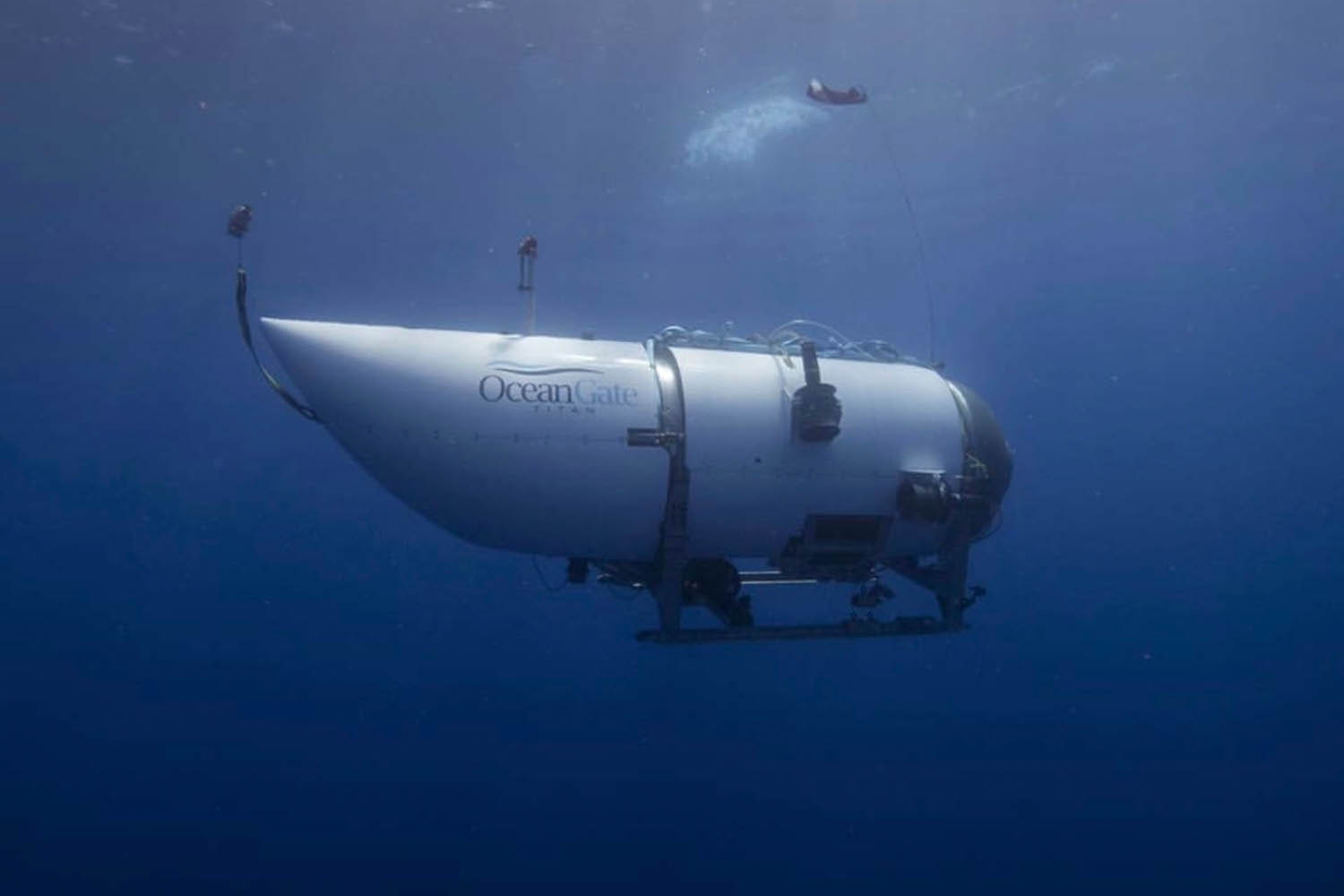

Equally defining of Glastonbury that year – but missing from the lineup, news reports and wraps – was the Titan submersible. Five passengers had each paid $250,000 to go on an eight-day expedition, diving 3,800m down to the Titanic wreck, and the vessel had gone missing on the Sunday before the start of the festival. By the time the gates opened to the public on Wednesday, it was the biggest news story in the world.

Glastonbury is often described as a sanctuary from real life. Like Brexit in 2016, this was a rare event of sufficient urgency (and, it must be said, novelty) to penetrate the festival’s protective bubble.

It lent a queasy extra layer of anticipation to the opening events. I remember punters discussing it in queues for the bar, and seeking out updates on the search effort whenever their phone resumed service. The sub was said to have 96 hours of oxygen supply on board. Before we were to leave Worthy Farm, it would either be found, perhaps with those on board miraculously alive, or all hope would be lost.

The question did not remain open for long. At 7pm GMT on Thursday, the US Coast Guard confirmed the discovery of a debris field consistent with an implosion. There were no survivors.

“I can’t remember exactly where we were when we found out,” says a friend, who was attending Glastonbury for the first time in 2023, and recalls the experience otherwise as start-to-finish euphoria. “But I remember everybody immediately shutting up about it. There was no follow-up discussion.”

Two years later, the Titan submersible has returned to public consciousness with the launch of not one but two documentaries about the disaster. The BBC released Implosion: The Titanic Sub Disaster in May. When Netflix followed two weeks later with Titan: The OceanGate Submersible Disaster, it became the platform’s most streamed property.

The films – which together total 170 minutes – overlap as much as their titles suggest, focusing on the US Coast Guard’s two-year investigation into what happened. Both identify the fates of those on board as having been seeded years earlier, when Stockton Rush, the founder and CEO of OceanGate, which organised the dive, first set his sights on conquering the deep sea.

Stockton Rush in a still featured in Implosion: The Titanic Sub Disaster, BBC

The revelations – corners cut, regulatory oversight eluded and failures wilfully ignored – are nauseating. The footage of the claustrophobic quarters inside the sub make vivid the men’s final hours; the sight of the PlayStation controller, famously used to operate the vessel, acts as a reminder of Rush’s fatal hubris.

Rush is portrayed as a rich and powerful egomaniac, emboldened by his privilege – his lineage is traceable to the Mayflower – to bully employees into silence. Rush reportedly spoke of paying to make problems go away and embraced a tech-bro mentality of “fail fast, fail often”. “He wanted to be a Jeff Bezos or an Elon Musk,” says a former employee. The OceanGate tragedy is thus cast as another round in the battle of “big swinging dicks” – as Rush is said to have described Musk and co admiringly.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Audiences have developed an appetite for these types of stories over the past decade. If the TV series Succession lifted the lid on the men who run the world, then Triangle of Sadness and The Menu satisfied a primal desire to see them get their comeuppance. Both films were released in 2022, less than a year before the Titan disaster; Succession concluded, after four seasons, the month before.

As well as the trend for “eat the rich” narratives – showing one percenters meeting sticky ends – the global reaction to the Titan disaster was revealing of the broken-down distinction between fact and fiction, and audiences’ growing sense of entitlement to participate in both equally.

Earlier in 2023, people had descended upon a Lancashire village to personally “investigate” the disappearance of Nicola Bulley. The following year, social media sleuthing into the real-life inspirations behind Baby Reindeer led to an ongoing defamation lawsuit against Netflix, obliging the streamer to acknowledge that what it had called a “true story” is, in fact, partly fictionalised.

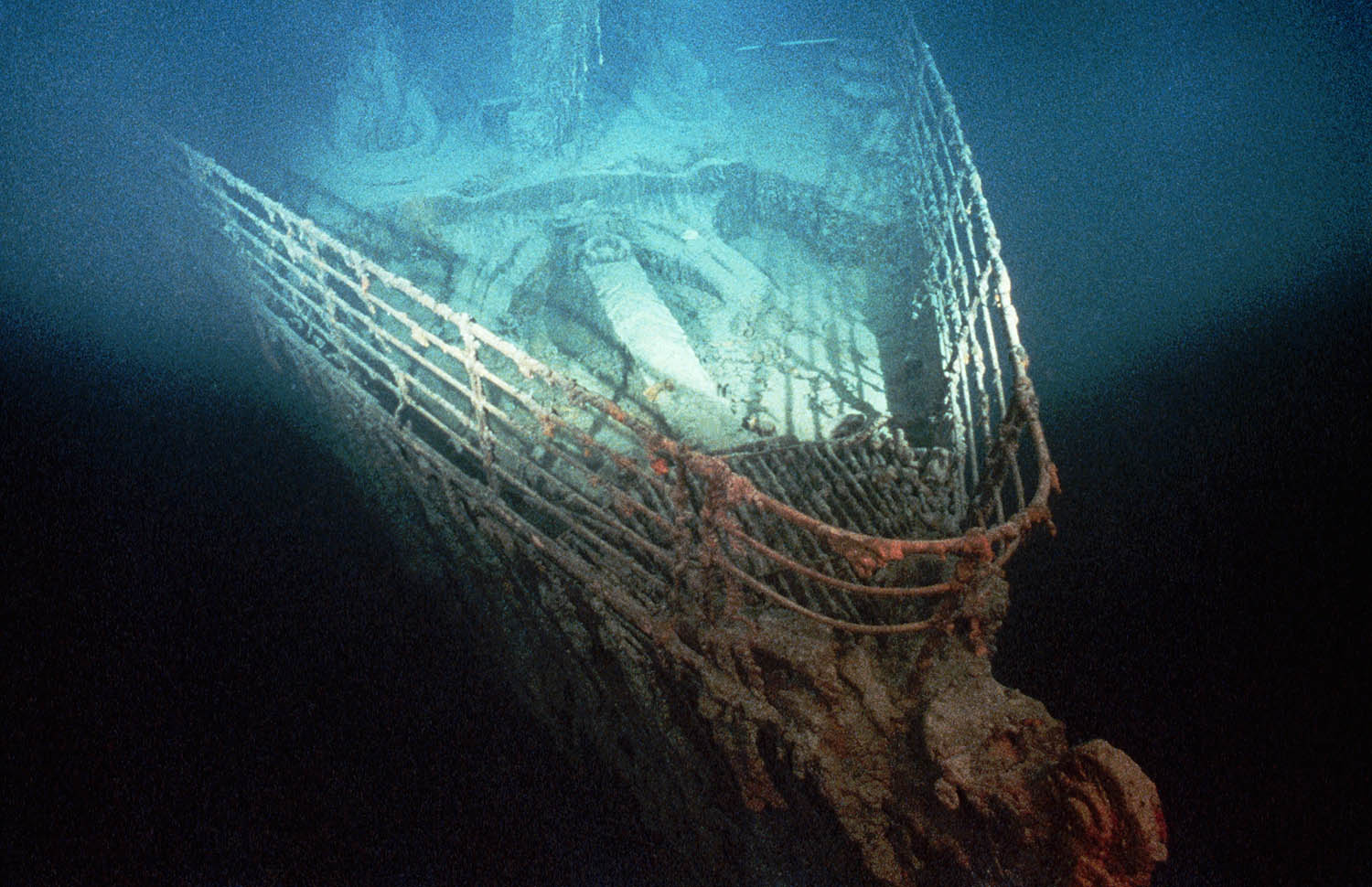

The Titanic l largely intact at a depth of 12,000 feet off the coast of St. John's, Newfoundland.

The closest parallel, in the sweep and immediacy of the global response, might be the Thai cave rescue of 2018, when 12 boys and their football coach were trapped below ground for 15 days. But they were children. The public was – to a point – restrained.

The five lives at stake on the Titan were men, majority white and uniformly rich, making them – by social media measures of decency at least – the fairest of game. It was considered to be the definition of punching up.

The least charitable view, widely voiced online while the search effort was still underway, was that they were disaster tourists who had paid $250,000 to gawk at a mass grave – and deserved what they got.

Both documentaries strenuously reject that view, setting out how grossly the passengers were misled. Rush did not so much fail in his duty of care as refuse to acknowledge he had one.

The story had Titanic, it had billionaires, it had running out of time

The story had Titanic, it had billionaires, it had running out of time

An OceanGate employee

But neither documentary really attempts to paint a picture of any of the men on board the sub – with the exception in Titan of the trailblazing and highly credible French diver Paul-Henri Nargeolet. Over a 50-year career the film seems to suggest that Nargeolet, known as Mr Titanic, had earned his right to explore the deep sea.

But what about the billionaire businessmen who could simply afford to go? How do you depict them to audiences not necessarily inclined to sympathise?

Implosion features moving testimony from Christine Dawood about the loss of her husband Shahzada and 19-year-old son Suleman on board. But it does not interrogate their motivations for wanting to see the Titanic wreck, attempt to justify their right to go, or even portray them as individuals.

The tragedy identified is the highly preventable loss of life – with the blame laid squarely with Rush, OceanGate’s rich-guy villain. The question of whether deep-sea tourism should exist – and whether anyone should have $250,000 to spend on it – is murkier and left unanswered.

What if, by some miracle, everybody onboard had survived? Would the news have been announced at Glastonbury – as I’d fleetingly hallucinated might be possible at the time – live from the Pyramid stage by Rick Astley or Dave Grohl? What documentaries would we be sitting down to now?

Eventually, you can imagine, they would have been called on to defend their decision to dive to the Titanic, their hubris, their wealth that made it possible. In death they are static. Symbols left open to interpretation and bit-parts in a story that has never really been about them.

From the start, the Titan sub was more legible as a narrative than reality. Even those directly connected speak of it in those terms. “The story had the ingredients,” a former OceanGate employee says in the opening minutes of Titan. “It had Titanic, it had billionaires, it had running out of time.”

In Implosion, Christine Dawood says receiving the news of her husband and son’s fates was like finding herself in “a real crime horror film”; another OceanGate whistleblower went for a “surrealist movie”.

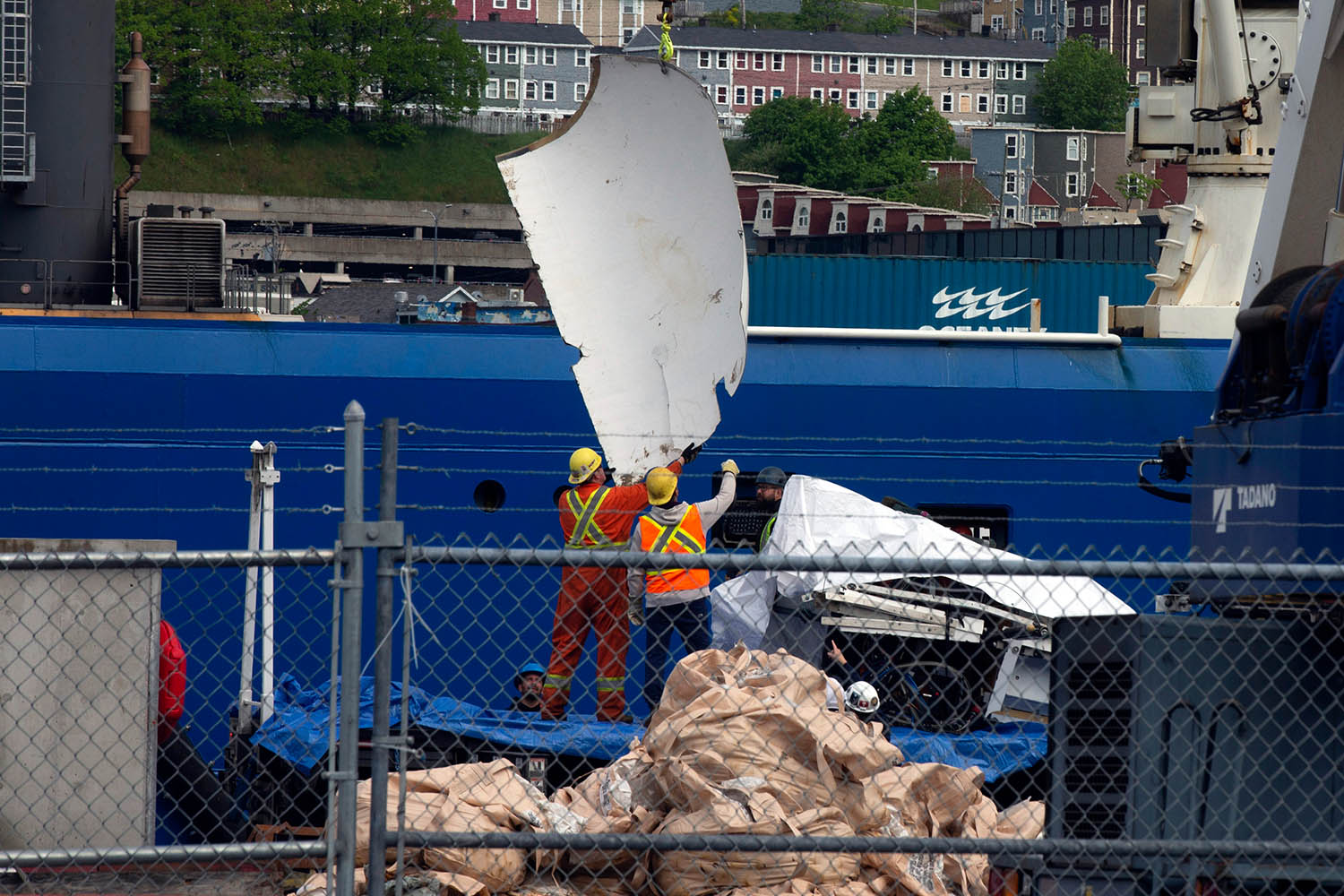

Debris from the Titan submersible, recovered from the ocean floor near the wreck of the Titanic, is unloaded from the ship Horizon Arctic at the Canadian Coast Guard pier in St. John's, Newfoundland

As soon as it went missing, the Titan sub was pure story; all Netflix and the BBC production had to do was package it up.

But even a delay of two years might have been premature. No criminal charges have been laid in connection to the five deaths; the US Coast Guard’s final report has yet to be released. As a result, both films feel somewhat inconclusive, even as they purport to be the definitive version of events.

“Accessibility is ownership,” Rush used to say, according to the videographer he hired to publicise OceanGate to one percenters as their once-in-a-lifetime ticket to the Titanic wreck.

He meant it as a rallying message, a workaround for petty regulations and laws. It doesn’t matter if you don’t have jurisdiction over the open ocean or the deep sea, if you can get there first; the first step, in making your vision reality, is feeling entitled to do so.

But it was portentous of Rush’s death: everyone had access. Everyone felt ownership.

Photographs by GDA via AP, Paul Daly/The Canadian Press via AP, Robert Ballard/Corbis via Getty Images