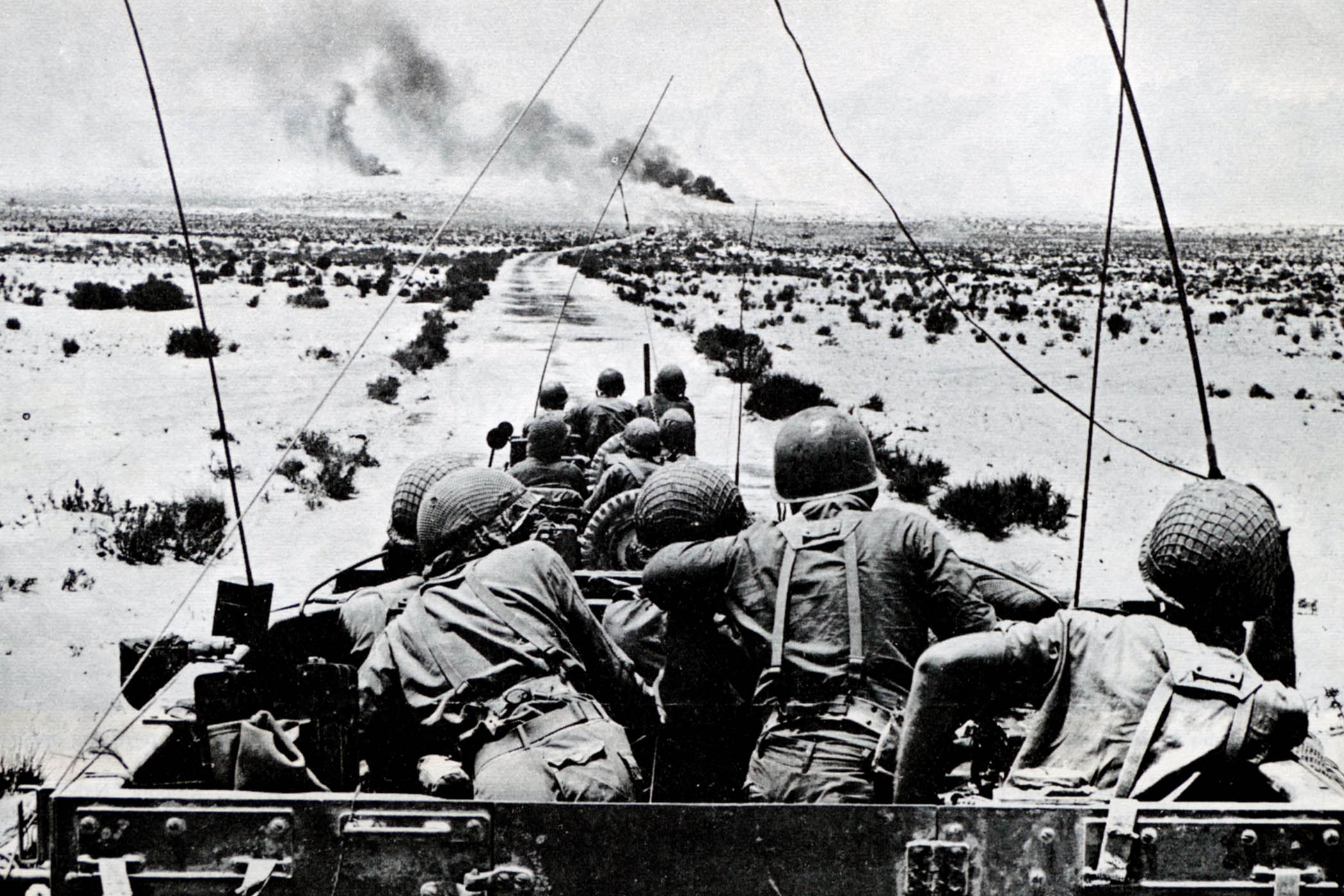

Iran and Israel were not always enemies. During the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), Israel was the only reliable and consistent western supplier of materiel to the Iranians. The US, western Europe and the Soviet Union all backed and supplied Iraq. Israel judged that Iraq was a far greater threat to it than Iran – and that Israel’s interests lay in prolonging the war and weakening both sides.

Israel and Iran also cooperated closely on intelligence. On 7 June 1981 the Israeli air force launched an attack on the Iraqi nuclear facility Osirak, just outside Baghdad. Iran provided a lot of the overhead photography, which enabled better targeting by Israeli planes.

At the time, the US and Israel were far from holding a common position: the US backed UN security council resolution 487, which “strongly condemns [Israel’s] military attack” on Osirak. That was a long time ago, of course.

There are regular power outages. The economy has been tanking

There are regular power outages. The economy has been tanking

More recently, the Iranians have been shifting their public position on nuclear weapons. For decades the Iranians have said nuclear weapons form no part of their nuclear programme; they quoted the fatwa of Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the religious edict published in the 1990s prohibiting the development of nuclear weapons on ethical grounds. This has long strained credulity: why has Iran been enriching uranium beyond 60% U-235 if not as precursor to developing nuclear warheads?

But in the last few years, regime insiders have been floating the idea that perhaps Tehran is going to be forced into making nuclear weapons – and, by the way, that it wouldn’t take that long.

Kamal Kharazi, Iran’s foreign minister when I was foreign secretary, and an impressive regime insider, said in May last year in an interview with Al Jazeera: “If the enemy threatens us, what should we do? We will be forced to make some changes [to our nuclear doctrine].” In October last year, 39 members of the Majlis, the Iranian national legislative body, sent an open letter to the supreme national security council calling for a review of the country’s nuclear doctrine. Previously, those voices would have been silenced for questioning the fatwa. In recent months, senior figures in the regime have been putting a toe in the water, testing their own government’s willingness to change its public position on nuclear weapons.

The biggest question – to which we cannot pretend to have an answer – is whether this will hasten the collapse of the regime in Tehran. The fact is, you can only judge the makings of a revolution after the event. But there is a sense that things are getting towards the endgame – that it is close to collapse.

Popular consent – even sullen consent – for the regime has been markedly weakening ever since suppression of the demonstrations against the rigging of the 2009 elections. Even though Iran has vast oil and gas reserves, there are regular power outages; the economy has been tanking, not just as a result of sanctions but of government incompetence, too. The fact that Israel’s intelligence agents were able to identify the locations of senior military personnel – “we know where you live” – is in itself a comment on the willingness of Iranians to give up information about their political and military masters.

Related articles:

As internal repression has tightened, so has the rhetoric about Israel. This has been led by Khamenei. He is a bitter, myopic old man and, I am sure, increasingly paranoid. He has got himself into a psychological trap. He has had no experience of the outside world. Since becoming supreme leader, 36 years ago, he has not been outside Iran once. The regime’s position, which denies the right of Israel to exist, has always been horrible but also nonsense; there has never been the remotest chance of it being successful. However, it’s hardly surprising that Israel has been profoundly anxious about the threat that a nuclear-armed Iran would pose.

This conflict between Khamenei and Benjamin Netanyahu was in many ways inevitable. In 1988 the founder of the Islamic republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, famously said that his regime and the Iranian nation would have to drink “a cup of poison” – that is a ceasefire – rather than continue the war, which they were by then losing. That’s the choice now facing Khomeini’s successor. Drink the poison – do the nuclear deal on offer from Donald Trump. The alternative is much worse.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Jack Straw was the UK foreign secretary from 2001 to 2006, and was the first British foreign secretary to visit Iran after the 1979 revolution. He is the author of The English Job: Understanding Iran and Why It Distrusts Britain

Photograph by Iranian Leader Press Office/Anadolu via Getty