‘What happened? Why did it happen? How could it have happened?” asked Hannah Arendt in a preface to The Origins of Totalitarianism. These were “questions with which my generation had been forced to live for the better part of its adult life”.

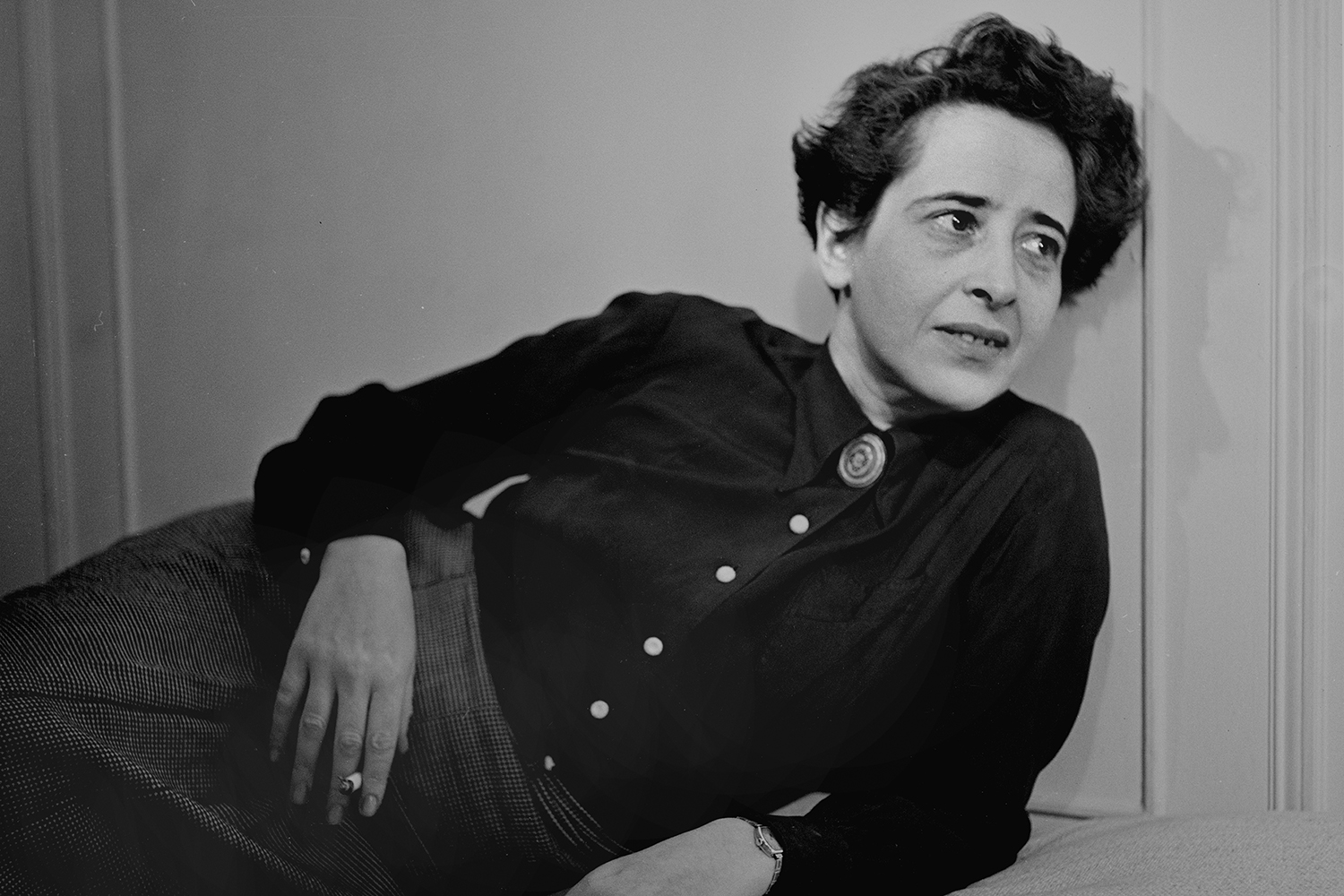

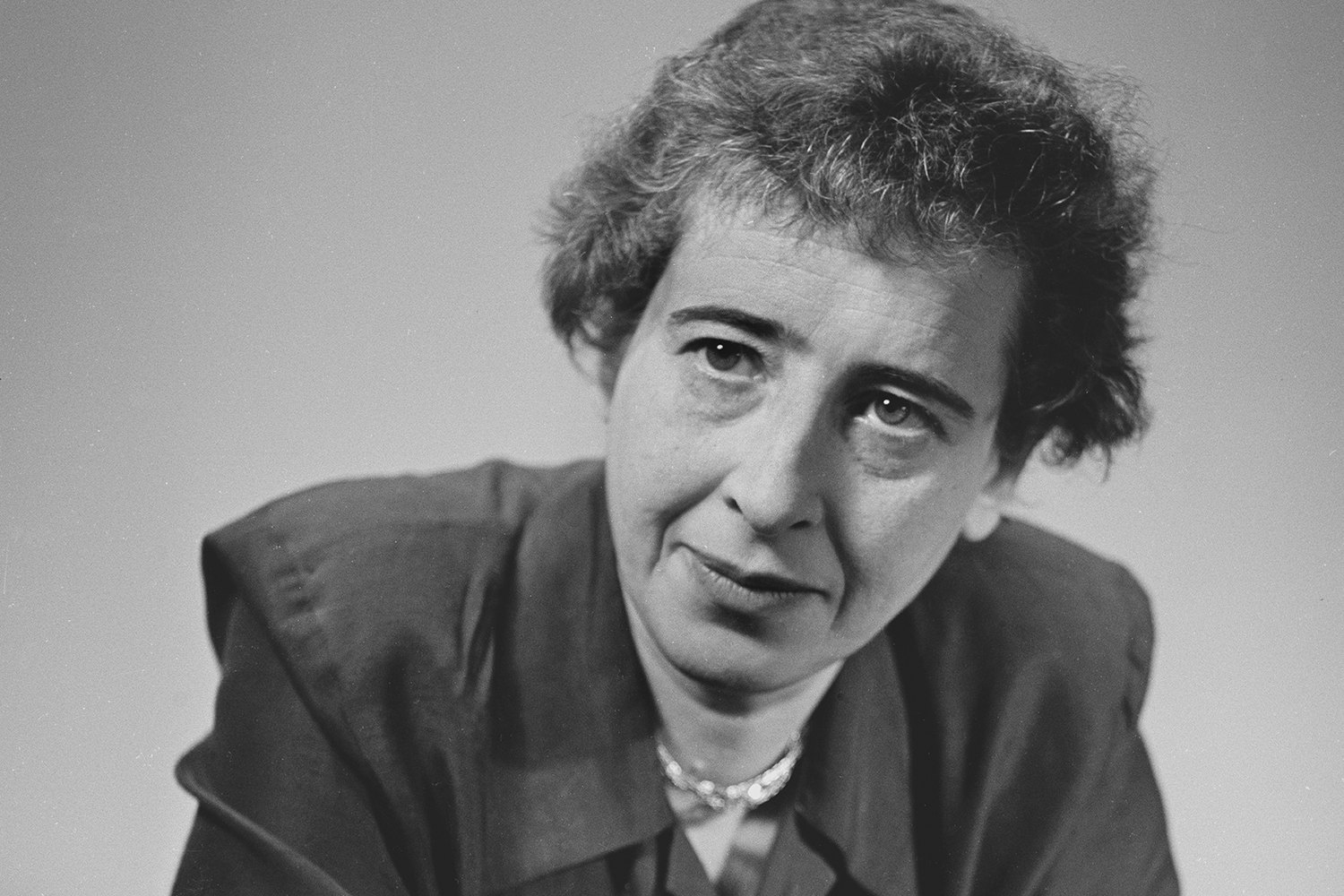

Among the most influential political thinkers of the 20th century, Arendt had, as a Jew, fled Nazi Germany in 1933, eventually finding refuge in America. Now a new edition of her famous 1951 work, including two additional chapters, has been published.

The Origins was not conceived as a book about totalitarianism. The first two parts dissect antisemitism and imperialism, respectively. Written in the mid-1940s, these two sections were to have been the core of the book, with a concluding chapter, “Race-Imperialism”, on the Holocaust.

Then came the cold war. A third section on totalitarianism – “largely an afterthought”, the Arendt scholar Margaret Canovan observed – was written as the iron curtain descended and the Berlin airlift began. Arendt’s inventory of “elements” underlying totalitarianism – imperialism, racism, antisemitism, the decay of the nation state, the “alliance of capital and the mob” – made more sense in relation to Nazism than to Stalinism. But as the cold war intensified, critics ignored much of this – especially Arendt’s autopsy of imperialism – in favour of a simplistic analogy between two totalitarian systems. Which is a pity, because the themes that preoccupied Arendt are central to our world, too. Her ideas should still command our attention.

Hannah Arendt speaks as eloquently to our world as she did to interwar Europe

Hannah Arendt speaks as eloquently to our world as she did to interwar Europe

The “scramble for Africa” at the end of the 19th century, Arendt argued, inaugurated a new imperialism that was “the preparatory stage for coming catastrophes”. Expansion became an end in itself. A new form of racism so dehumanised colonial subjects they were transformed into objects for extermination. A novel kind of bureaucracy substituted for democratic governance, and brute violence replaced the rule of law.

The large-scale slaughter of colonised peoples had long preceded the scramble for Africa. Arendt’s description of colonial racism was itself tainted by racism. “The overwhelming monstrosity of Africa – a whole continent populated and overpopulated by savages,” she wrote – “so frightened” Europeans that “civilised man … no longer cared to belong to the same human race” as the “savages”.

Yet for all her blind spots and prejudices, in showing how imperialism forged a template for totalitarian rule, Arendt was closer to anticolonial thinkers such as Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon than to most European intellectuals of the time. Europeans, observed Césaire, the Martinican poet and statesman, had “tolerated Nazism before it was inflicted on them”, had “absolved it, shut their eyes to it, legitimised it, because, until then, it had been applied only to non-European peoples”. Today, as many seek to whitewash the reality of empire, it’s an observation we should not forget.

Linked to the new imperialism, and the process of dehumanisation was the loss of what Arendt called “the right to have rights”. Humans acquire rights only as members of a political community, primarily the nation-state. When people are stripped of their place in such communities, and turned into non-citizens, their rights disappear. So it was with colonial subjects under imperialism. And in Europe, as the political order disintegrated after the first world war, millions were left stateless, as refugees or as minorities without rights. In both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, the severing of people from the political community had monstrous consequences. “The world,” Arendt wrote in a phrase that still haunts, “found nothing sacred in the abstract nakedness of being human”.

The loss of the right to have rights is not unique to totalitarian states. Think of the thousands of potential migrants imprisoned in North Africa at the behest of the EU; asylum seekers made “illegal” and denied rights in Britain; American green card-holders deported for wrong speech – a class of non-citizens stripped of liberties as liberal democracies wrestle with questions of immigration and national sovereignty. Arendt’s argument speaks as eloquently to the contemporary world as it did to interwar Europe.

The other main theme of The Origins – antisemitism – is an equally critical issue today. Just as a new racism developed towards the end of the 19th century, so, Arendt argues, did a new antisemitism. Against the background of emancipation, Jewishness became viewed less as an external religious distinction than as a hidden racial quality. Old conspiracy theories took on new, racialised forms, leading eventually to the “final solution”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The plight of Jews, Arendt believed, could be resolved only in solidarity with other oppressed groups. She had a deep investment in Zionist politics; what she hoped for, though, was not a Jewish nation state but a “Jewish national home” within a binational Palestine.

With the creation of Israel as a “colonised and then conquered territory”, she wrote in The Origins, the “solution of the Jewish question” had produced new victims, Palestinians now becoming “stateless and rightless” and forced to choose, as she warned in her 1944 essay Zionism Reconsidered, “between voluntary emigration or second-class citizenship”. She condemned a Zionism “that felt no solidarity with other oppressed peoples whose cause … was essentially the same”. Again, the resonances with today’s debates and conflicts are clear.

Arendt was a complex and sometimes contradictory thinker. She was often wrong. Yet her work still speaks to us, not least because of the fierceness of her fearlessness, her willingness to “think without a banister”. It’s a quality that, sadly, is in short supply today.