I’ve been editing the work of a writer whose first language is French; but her English is absolutely fluent, and she is writing her novel in that language. Only occasionally does her native tongue slip through, as when she will refer to “the father”, as the parent of her protagonist. Let’s call him Simon, this protagonist. So, we have: “The father gets up from the table.” In English, we would be more likely to say, “Simon’s father gets up from the table”, a construction that isn’t possible in French. “The father” sounds natural to my student, because “le père” sounds natural in French. In English it conveys a formality that she did not hear until it was pointed out to her.

Do we make language or does language make us? The beauty of it is that we can – if we allow ourselves – pick and choose. I grew up being told that I was weird, a word of bullies and, let’s just say it out loud, losers. It took many decades for me to perceive that weird and queer are synonyms, at least of a kind: for no word in English is ever truly the real equivalent of another. This was, and is, an understanding that was supremely liberating, freeing me in my present and releasing me from the past.

In the anecdote above I might have said “their English is absolutely fluent” and I certainly would have if that is how this person chose to identify. Even if they – if she – didn’t, the use of “they” would have further anonymised my subject. That would have been a truly gender-neutral use of the word: but to use “they” in reference to one person is both gender-neutral and, at the very same time, also not gender-neutral, because it unavoidably expresses a wish to be perceived outside the binary. As with so many complex issues, both things can be true at once.

“Call me Ishmael,” announces the narrator of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick – so this may or may not be his name. It is, as we would say now, how he chooses to identify. Among other things this foundational novel of the US is a homoerotic wonder: “Upon waking next morning about daylight, I found Queequeg’s arm thrown over me in the most loving and affectionate manner. You had almost thought I had been his wife.” But Ahab’s quest, and Melville’s, is in a larger sense “about” how we define ourselves. What is Ahab without his whale? Over and over again Ishmael works to describe the whale: his repeated attempts, the extraordinary and various forms of the novel, contain and illuminate both failure (the whale refuses definition) and success (there is glory in the pursuit, of the whale, of the word).

We are always mediating between the sense of self that we carry and the way the world perceives us

We are always mediating between the sense of self that we carry and the way the world perceives us

When I consider how language can either free us or imprison us, I often find myself looking to the past, to texts that exist in the fluid space before the 21st-century fixation on narrow definitions of the self. This is not to romanticise eras in which homosexuality was illegal, when deviations from codes of behaviour could come at a high cost. Not that any of this is safely “in the past”: more than 60 countries around the world still criminalise consensual same-sex sexual activity. I speak of the most private self, or, perhaps most truthfully, my own private self, the only one I can ever truly know. I consider the boundaries between languages because I believe we are always “in translation”, mediating between the sense of self that we carry and the way the world perceives us.

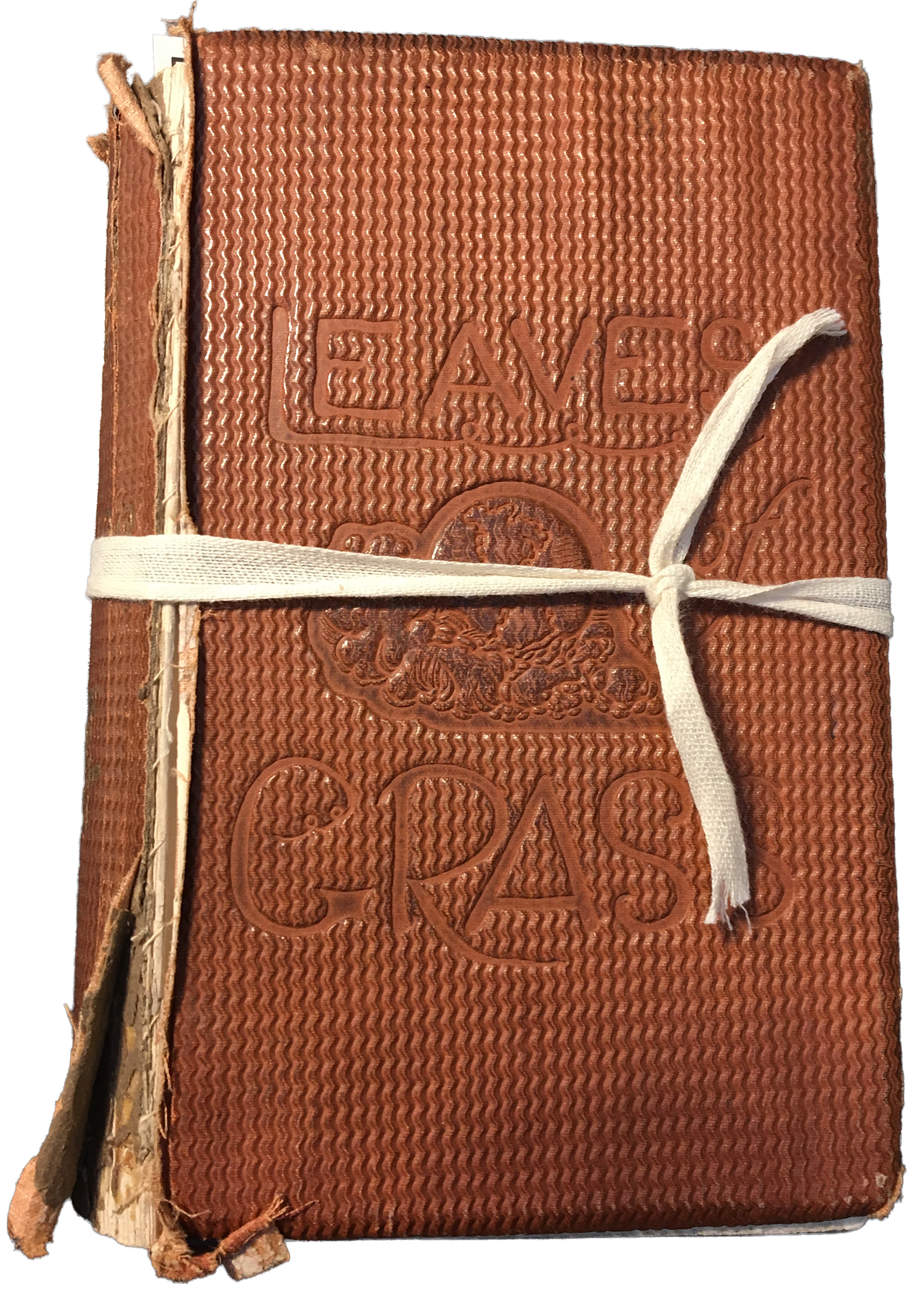

There was a period when, while working in the British Library, I used to keep a copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass on my desk. It wasn’t connected to the research I was doing: I simply felt it was something I wanted, or needed, to have near me. (Our wants, our needs: another challenging distinction.) I would consult it like an oracle. It felt miraculous that I was permitted simply to ask for it, and a librarian would bring me the edition of 1860; about 2,000 of them were printed. The brown binding is embossed with the title and a natural scene; the book is fragile now, and arrives in a grey box, the text itself tied with string. As the Whitman Archive has it: “The book’s pages were well-printed in a clear ten-point type on heavy white paper and elaborately decorated with line-drawings around titles and the beginning and end of poems.”

The British Library’s copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

I was looking for the song of myself; I turned to Whitman even before I understood what it was I was looking for. “Are you the new person drawn toward me, and asking something significant from me?/ To begin with, take warning – I am probably far different from what you suppose;/ Do you suppose you will find in me your ideal?/ Do you think it so easy to have me become your lover?” When my lover appeared on the horizon, Whitman’s mutability, his openness, his curiosity, had prepared me. Now I keep by my bed the gorgeous, deluxe two-volume edition – complete with ephemera, drafts, reproductions of handwritten pages – recently published by McSweeney’s in close collaboration with the Whitman Archive.

Whitman and I are separated by centuries, by sex, by belief. Yet in language we can meet and speak, in the absolute privacy and liberation offered by text. Anne Carson, in her remarkable essay Eros the Bittersweet – a book, now acknowledged as a classic, that is not only an examination of Ancient Greek literature but also an expansion on the possible impossibility of love, acknowledging as it does that “eros” only truly exists in longing, and vanishes when the object of that longing is grasped – considers how the development of an alphabet actually drove the creation of the idea we call “privacy”. Before writing, words were exchanged and vanished; or were declaimed for a crowd: “All communication is to some extent public in a society without writing,” she notes. With the alphabet came a new possibility: “Letters make the absent present, and in an exclusive way, as if they were a private code from writer to reader.” This private code can be deciphered and deciphered again down the millennia, each generation and each reader finding the key to the self in the text.

As Whitman wrote: “I exist as I am, that is enough./ If no other in the world be aware I sit content,/ And if each and all be aware I sit content.” I offer no answers; only this longing for the true self, one which can never – to my mind – be resolved, and that is longing’s gift.

Photographs by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images, Courtesy Erica Wagner

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy