Last week was when Maga came after multilateralism. Nicolás Maduro may, or may not, be the drug cartel leader Donald Trump claims, but he certainly stole the last Venezuelan election and several before, has driven almost a quarter of his population into exile, imprisoned and killed opponents, impoverished what was Latin America’s richest country and is a crook to boot who has entrenched corruption across what’s left of the economy.

But the world hadn’t until now found any mechanism to effectively hold him to account. Indeed, his UN representatives sometimes seemed to enjoy a perverse celebrity for their Yankee-bashing stands as part of a network that includes Cuba, North Korea, Iran and Russia but often expands to a much wider grouping.

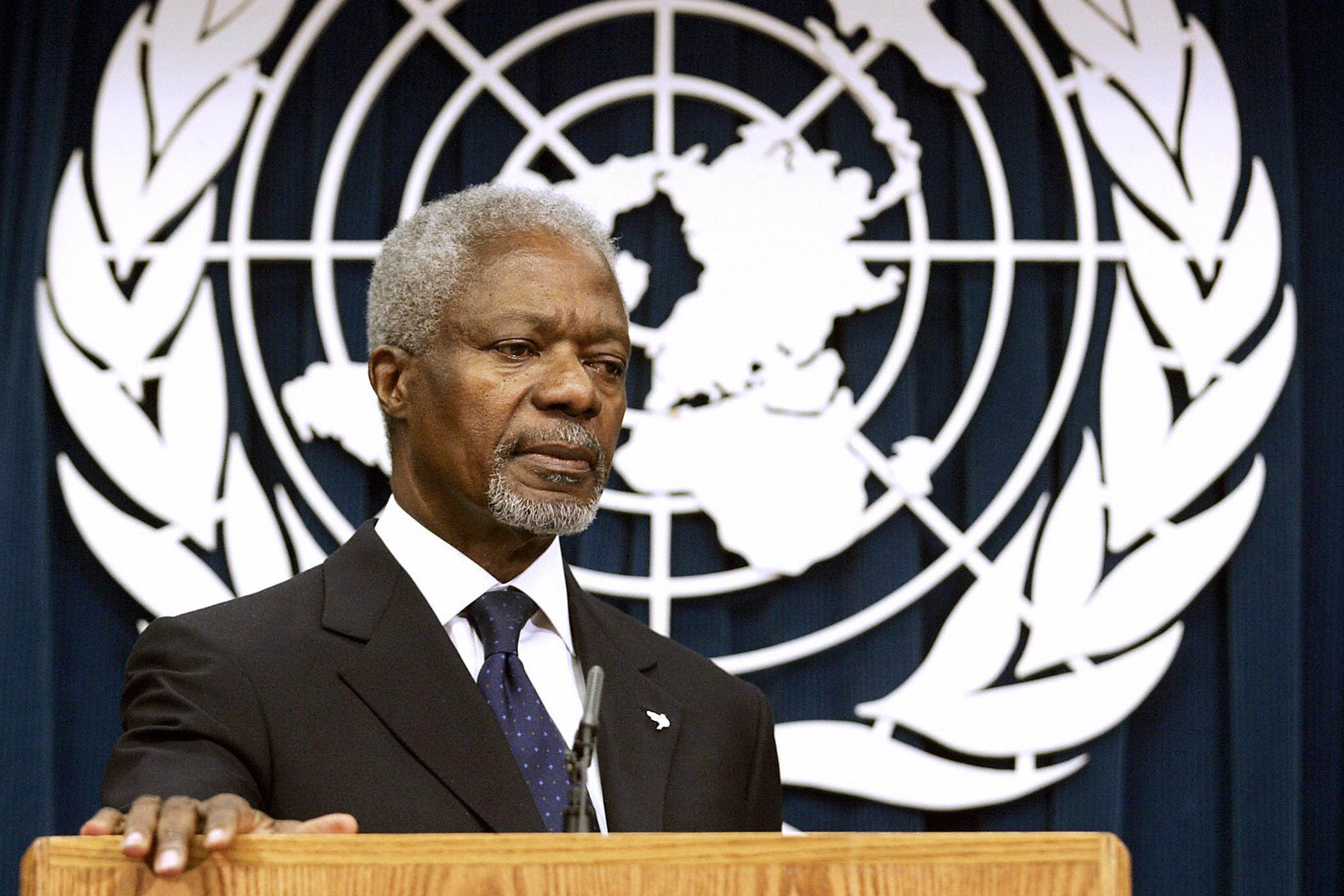

Nevertheless, I would have been deeply critical of the US action if I had spoken at last week’s security council debate on Venezuela. It is a core premise of the UN that strong states don’t invade their neighbours. Twenty years ago, then UN secretary general Kofi Annan and I, as his deputy, fought to establish the doctrine of the supposed “responsibility to protect” as a critical caveat to sovereignty.

We saw it as essential to the UN’s future legitimacy. This enshrined the idea that malicious governments did not have the last word on the wellbeing of their citizens, and that when domestic tyranny met certain grim tests of murderous badness, was a threat to international peace and failed to respond to lesser pressures for correction, an armed intervention could be sanctioned by the security council for the carefully defined and limited purpose of correcting those wrongs.

Annan and I were of a UN generation with searing personal experience of the Khmer Rouge killing fields in Cambodia, the genocide in Rwanda and the massacres in Sarajevo and Srebrenica. We learned the hard way that the UN could not be an idle bystander, hiding behind the protocol of state sovereignty, as governments killed thousands and sometimes millions of their citizens.

Maduro should have been ousted by the combined efforts of regional and international organisations working through agreed rules

Maduro should have been ousted by the combined efforts of regional and international organisations working through agreed rules

Where was the responsibility to protect in the long years of Maduro’s destabilisation of Venezuela and its region? Nowhere to be found. Early missteps in its use, notably in Libya, had been exploited by its many powerful opponents – led by Russia and China – to it being essentially discarded. The UN, its human rights leaders apart, has largely in recent years deferred to the sovereignty of states over their own affairs. Despots could breathe easy again.

So when an African leader who has fought for years to improve his country’s lot through the thick and thin of civil war, bad governance and rife corruption texted me last week to say that we might not like Trump’s methods but we had to admire the outcome, it brought home how far the international system has fallen short. This should have been its job. Maduro should have been ousted by the combined efforts of regional and international organisations working by the book through agreed rules.

Kofi Annan and Mark Malloch Brown at a UN conference in New York in 2004

My friend’s view is that countries hiding behind the sovereignty argument, and international organisations eager not to cause offence, have created an epidemic of bad governance: aid is squandered, countries persecute their citizens without consequence, and the rash of bad governance, instability and conflict widens. A system that poses as a friend of the developing world has become in some cases an unintended enabler of bad behaviours.

Liberal critics of Trump find it hard to accept that a good part of his success is that he is seen to get things done. He is a champion of the maxim: move fast and break things. For many frustrated by the inertia of modern government with its sprawling costs, duplication and stifling bureaucracy, Trump is, or was, liberating fresh air.

Now he is applying the same sledgehammer internationally. On 7 January, he issued an executive order withdrawing US support from a labyrinthine list of 66 UN and other international bodies. He has already claimed that he is doing the UN’s job as the world’s chief peacemaker. His supposed peace agreements are mostly slapped-together photo opportunities that amount to a temporary ceasefire at best.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Nevertheless, abroad as at home, he exudes bustling energy and strength, while his critics – such as Democrats in Washington – seem keen to defend a failing international establishment rather than take him on his own terms and find alternative multilateralist solutions that outperform his “America first” playbook.

Trump’s world spelled out in his new national security strategy, is one of spheres of influence where the US dominates the western hemisphere as Russia and China do their own regions. The western hemisphere will from now forth, he has declared, be governed by what is best for Trump’s US. It is the antithesis of the UN’s world, of rules and laws where power alone is not the arbiter of justice. Rather, the UN model imagines collective action based on respect for universal principles and norms. That version of how the world should be run should now be fighting for its life. So far, it appears not to have stirred from its deep sleep.

In the years since the UN’s formation in 1945, its application has been riddled with double standards and has often come up short in resolving conflict – but it had also helped keep the peace, and manage an epic process of decolonisation and new nationhood, for which The Observer was a principal scribe and campaigner.

Now many of those gains are at risk as aid is slashed, conflict surges and a new lawlessness, championed by Vladimir Putin and Trump, reshapes the international order and threatens the independence of nations.

I write this from an ocean balcony in South Africa while I scan the seas for sightings of a long-planned naval exercise in which South Africa is hosting three fellow navies: Iran, China and Russia. The unintended timing, a week after Venezuela sends its own message. But it seems many South Africans would prefer to see their country as a leader in a renewed rule-based multilateralism than crouched in a defensive laager with these strange shipmates. And that’s the choice we all need to make – go along with Trump, side with his opponents or insist there is another way: a revived UN.

Mark Malloch Brown is the former deputy secretary general of the UN

Photographs by Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images, Don Emmert/AFP via Getty Images