How surprised were you when you realised Michelle Obama was not at Donald Trump’s inauguration? Were you admiring? Perhaps you were taken aback or envious that she, like Melania Trump, has chosen when to be a professional wife and when not to be one.

When, or rather, did the pleasure of being out and about with a partner fade for you? Did it wither into feeling just too much obligation? And was there a struggle to not show up for that funeral, that party, as a partner? For women I’ve seen in therapy, the struggle to act on that desire has been hard.

It seems subversive to generations of women (and men) accustomed to having their spouses accompany them, to see a president devoid of his wife in public. The woman should be there. How can she be so brazen, stroppy or fearless? Yet when a woman can jump into that new space, it can be relieving and pleasing.

It's strange because even those of us who go about quite easily without partners can feel a twinge of irreverence seeing these women allowing themselves not to show up. That’s because it is bred in our psychic bones. When we see such changes, they are not nothing. They are startling.

For Melania and Michelle, however independently they forged their pre-presidential lives, their psyches, their demeanours, their wants, were honed by the values and behaviours of their parents – mainly mothers – who would have instilled, by example and commentary, a set of behaviours and expectations that would have encoded what was right and wrong and the opprobrium that their daughters challenging the norms would have generated. Especially as members of their generation and social positions.

The public performance of life, whether it is lived on TV screens, as with Michelle and Melania, or the perceived public of in the school, the village, work and the wider social circles we occupy, can hold considerable power for us all. We project on to one another, without much recognition of doing so, disapproval, envy, longing, praise. What we may want, how we think we should be, how hard we might find the struggle to say that “no, I don’t want to do that any more”, can jangle with what can feel like creaky internal structures that are reluctant to yield and women in public life, as spouses, hold a position we may not have even known, we cared about.

This is where a function of gossip and other, less mean types of conversations comes in. We are trying to find out how far we can cheer or whether we or those we know will join the criticism. Public wives are a Rorschach personality test. We’re assessing our views against the behaviours, statements or silences of others. Many will have both cheering thoughts and desires while noticing censoriousness inside of them. Changes in social norms – and this is a change – can engender everything from praise and admiration while a latent emotional hiccup inside us suggests this might just have been too daring. Growing up with princess imagery goes deep. We are susceptible to disciplining ourselves even when it’s not, decidedly not, in our interest.

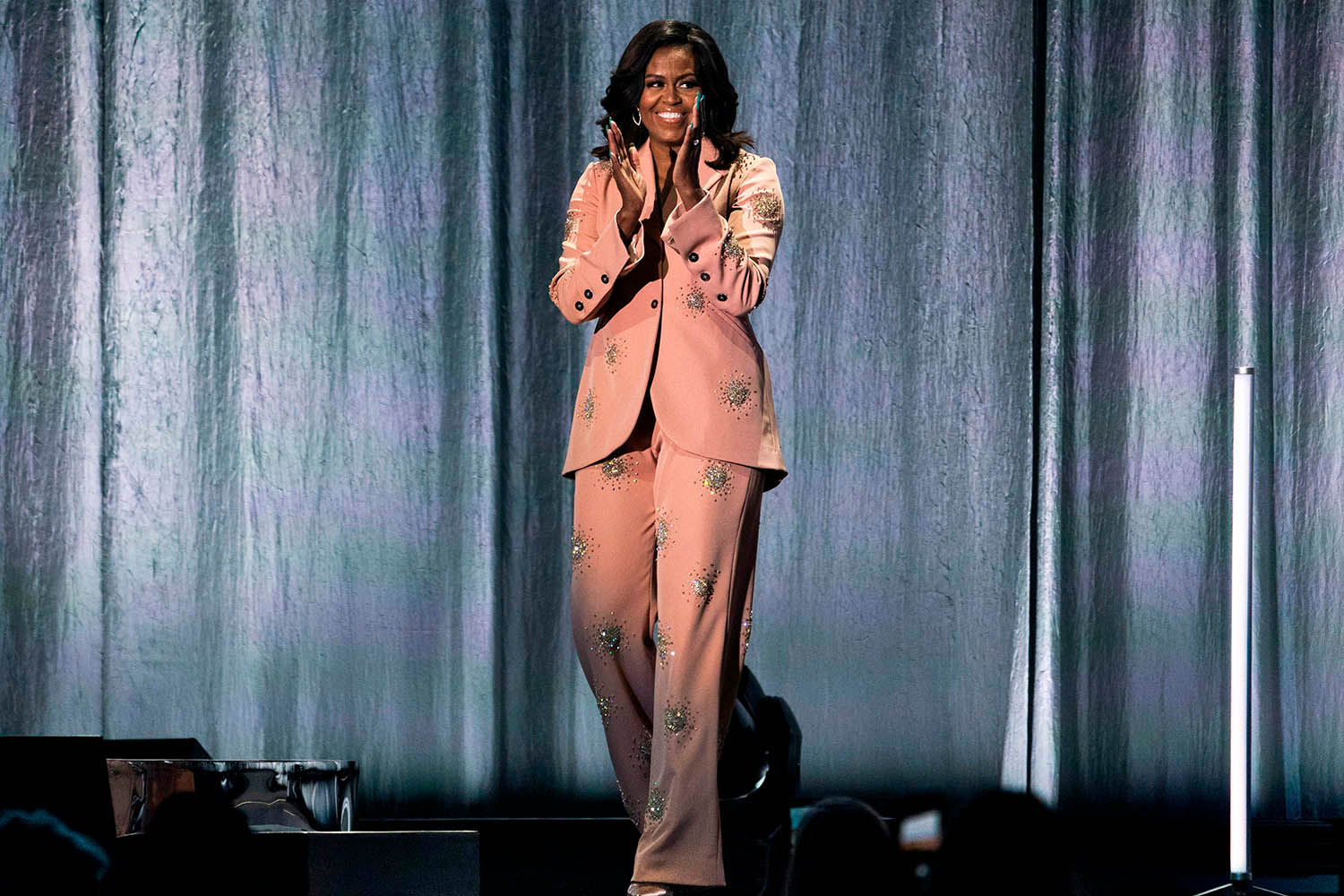

What is heartwarming about Michelle is her frankness about the struggle to catapult herself out of the limitation of living as a politician’s wife. required of her. Being prepared for every eventuality, of being needed to be anywhere and everywhere with suitable clothing and sense of duty, with just the right dose of compassion or seriousness, or warmth or dignity, was her role. She did it well. It was an extension of the old rules of ‘femininity’ and she showed the world how to do a modern version of it. She couldn’t have done it better. She was vibrant and engaged. Melania has shown us something different. She’s unreadable (and, unlike Michelle, doesn’t tell us); even when her jacket said: “I really don’t care, Do U?”, we weren’t sure what it meant. Were we surprised that we became momentarily preoccupied by it? Do we deem her inscrutable or mysterious which is another internalised view of what a woman could/should be?

Melania Trump and Michelle Obama, and their perceived actions become projections screens for what we want, what we abhor, what we think. Melania’s silence invites more of our imaginings perhaps, while Michelle Obama’s openness about her struggle to make choices for herself now that she is no longer a ‘professional’ wife, evokes more empathy. Those who groan and wish women would just keep their mouths shut and get on with the job show us how entrenched views of women can persist both inside of women and inside of men. The groaners aren’t necessarily saying they don’t care. They might just be saying ‘get on with it’. Having lived with a monarch who reigned during momentous changes in sexual relations and habits, we are used to a public sphere with certain rules despite the enormous changes over the past 50-plus years, in which girls and women have had work, family, and social lives independent of men and partners.

Queen Elizabeth II was mother of the nation when monarchy obliged. The presidents’ wives are now disobliging. I think I hear some excitement. They are refusing to be redundant women whose jobs have been to humanise and soften power. They are endeavouring to occupy their own spaces in their own ways as they offer themselves new possibilities.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photograph by Martin Sylvest/Getty Images