His father had hopes his son, Valentin-Yves Mudimbe, would become a manager at the mining company where he worked, but the young boy was a conspicuously cerebral child, what he called a “small, gifted dog”.

He was born on 8 December 1941 in the Swahili-speaking mining town Jadotville (now Likasi) in the then Belgian Congo, arguably the most brutalised of all colonies in Africa.

He was taken away from his family at the age of 10 by a Benedictine mission, where he trained to become a priest. He studied ancient Christian texts and read Greek and Latin, a colonial grounding in the classics that he later brought to his study of Africa’s oedipal relationship with its colonisers, while also challenging the scholarly traditions of which the classics were a key part.

Although Mudimbe, who has died aged 83, described the Benedictines as “the order which will most likely continue to colonise my life until I die,” he lost faith in the Catholic church when as a young monk in Rwanda he witnessed its support for Hutu ascendancy, and decided to reject a religious life. He majored in Romance philology at Lovanium University in Kinshasa, then sociology and applied linguistics in France, before gaining a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Louvain in Belgium. A gifted linguist, he was said to speak 10 languages and read in another eight.

Returning to what had become the Democratic Republic of the Congo, he taught at the University of Lubumbashi in the 1970s, part of a group of intellectuals de gauche that included the woman he would marry, Elisabeth Boyi. Mudimbe quickly made a name for himself as one the country’s leading thinkers, but that reputation became problematic when the kleptomaniac dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, in a moment of a characteristic caprice, offered the philosopher a role on his central committee as head of ideology, effectively a cabinet position.

Renamed Zaire by Mobutu, the country was enduring a particularly rampant period of human rights violations. Mudimbe wanted no part in the government, but the dictator’s offers were frequently proving unhealthy to refuse. So he wrote Mobutu a letter saying that he had a problem with his vision and needed to see an ophthalmologist in Paris. It was a difference of political vision.

He fled Zaire (later to become the Democratic Republic of Congo again in 1980), for the US, where he built a good life with Elisabeth, who taught at Stanford, and their two sons, who now live in California. Lecture excursions and visiting professorships aside, Mudimbe would remain in America for the rest of his life, initially teaching comparative religions at Haverford College in Pennsylvania.

In 1988, he published The Invention of Africa. It was a landmark in postcolonial studies, serving for a generation of African intellectuals as their continent’s equivalent of Edward Said’s Orientalism. If the African philosopher, poet and novelist was much less well known than his Palestinian-American counterpart, he was no less respected. He was instrumental in showing how embedded colonial attitudes are within the humanities.

Related articles:

Inspired by French thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Michel Foucault, he dug deep into African history to understand the social and cultural impact of colonialism, challenging Eurocentric Heart of Darkness cliches about the continent and the simplistic identity under which it had been condescendingly placed.

He wrote across disciplines (literature, anthropology, history, philosophy, cultural studies) and literary forms (essays, poems, novels) to create a body of work that was as complex as it was diverse. Both characteristics may have accounted for his relative lack of recognition beyond the field of African studies.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“His major contribution was in the field of the social sciences,” says Prof Pierre-Philippe Fraiture of Warwick University. “His whole work is about the position of Africa vis-a-vis the western world. He was a critic of humanism because it had allowed a two-tiered humanity, but he was not anti-humanist. He was never an advocate of identity politics.”

He was a critic of humanism because it allowed a two-tiered humanity, but he wasn’t anti-humanist. He was never an advocate of identity politics

He was a critic of humanism because it allowed a two-tiered humanity, but he wasn’t anti-humanist. He was never an advocate of identity politics

Prof Pierre-Philippe Fraiture, Warwick University

He was a “delightful individual, very erudite and generous with his knowledge, but a tortured man torn between two intellectual legacies”.

The publication of The Invention of Africa brought him to the attention of Fredric Jameson, the renowned political and literary theorist, who recruited him to the literature department at Duke University. He was the Newman Ivey White Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Literature when he died.

Yet despite becoming an American citizen, a big part of Mudimbe remained in Africa, which retained its position at the core of his work. Not long before he died he donated his personal library of 8,000 volumes to his old university in Katanga province. It was 45 years after he left the DRC.

Mudimbe may have been thinking about his homeland when he departed to the land of the ancestors, to use an African phrase.

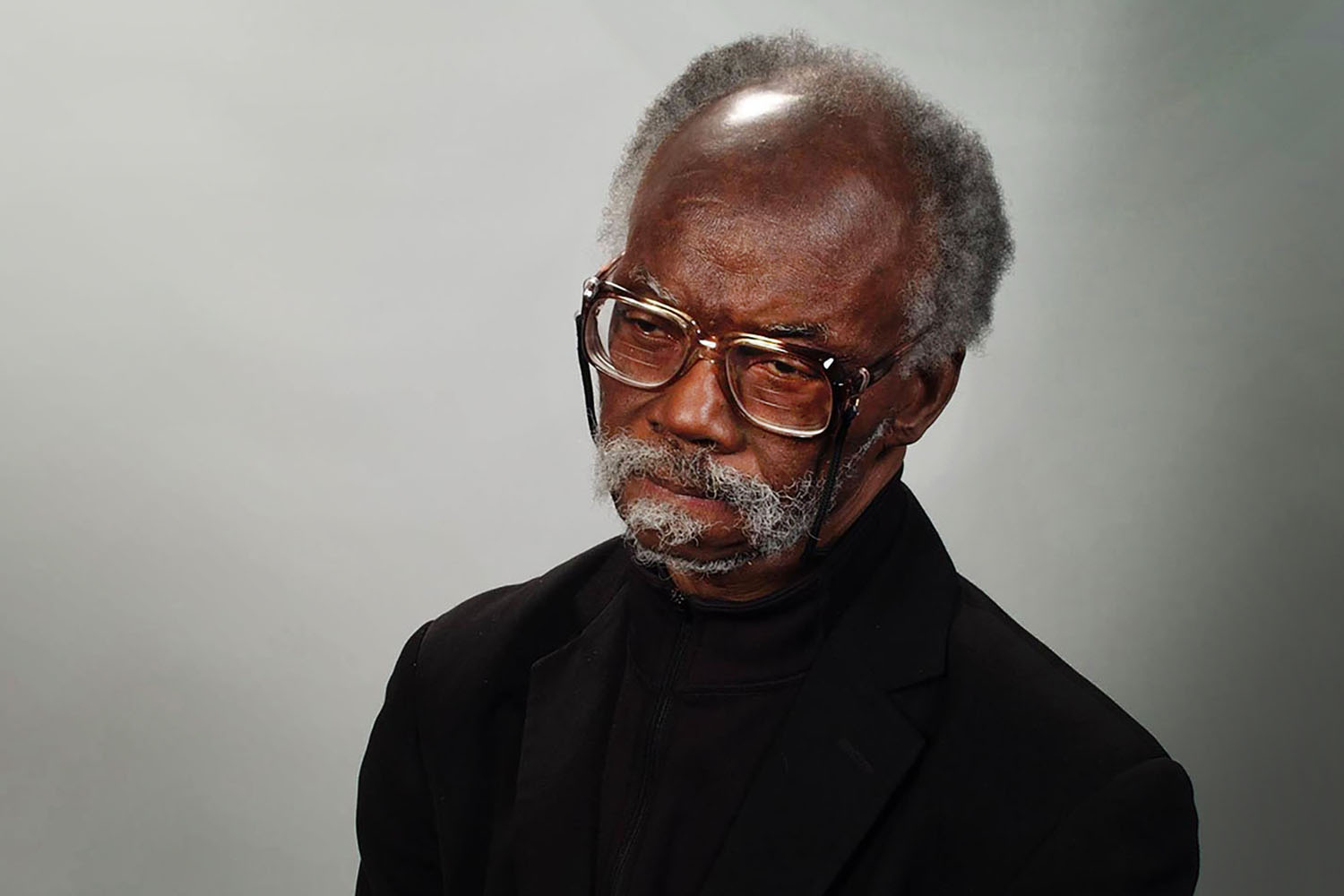

He was also a product of French existentialism, not just its ideas but also its personal aesthetic. Mudimbe favoured the black clothes and Gauloises look, an image that is captured in a photograph on one book cover of him sucking deeply on a cigarette, his narrowed eyes lost in thought. “He was an avid smoker,” Fraiture laughs. “And a great believer in freedom.”