HG Wells made his name predicting where mankind might be going, but it was his explanation of where we had been that gave a group of children in Auschwitz the hope that they might have a future – or at least a slightly more bearable present.

A Short History of the World, published in 1922 and translated into Czech, was one of barely a dozen books curated by the 14-year-old Dita Kraus for her fellow prisoners. As a library, it was tiny; as a small piece of joy amid such despair, it was immense.

At Auschwitz she worked in the “kinderblock”, block 31, run by a charismatic Jewish youth leader called Fredy Hirsch who had persuaded the camp commandant to create a daycare centre for children. Older children, Kraus among them, became his assistants and were given chores such as cleaning or cooking.

Kraus was asked to manage the small library of books that had been found in the luggage of arrivals. Though Wells’s history was the only title she could later recall, other survivors remembered an atlas, a work by Sigmund Freud and a collection of stories by the Czech science fiction writer Karel Čapek.

If the Germans had found me with those books they might have killed me

If the Germans had found me with those books they might have killed me

“It was my responsibility to safeguard these precious volumes,” Kraus wrote. “At the end of each day, I carefully collected the books and stowed them in a hidden location. If the Germans had found me with those books they might have killed me. The fact that I was able to sit indoors and not do strenuous work in the cold gave me a chance to save my strength and in fact enabled me to be chosen for life.”

Hirsch and his assistants would also pass on stories orally, telling the children tales such as Robinson Crusoe and The Count of Monte Cristo. Kraus called those who tried to teach and maintain the children’s spirits “the greatest heroes of all”, saying: “They knew they would die, yet dedicated themselves to the children, to make their last weeks as pleasant as they could.”

Prisoners did not live long at Auschwitz. On March 8 1944, those who had arrived the previous September were sent to the gas chambers. Hirsch, who had been informed of the impending murder, had been urged to lead an uprising but died from an overdose of sleeping pills. It was unclear if it was suicide or yet another killing.

The Spanish journalist Antonio Iturbe heard Kraus’s story and wrote a novel based on phone conversations called The Librarian of Auschwitz (2012). In 2020, Kraus, who felt Iturbe had over-stretched his imagination, published her own book, A Delayed Life.

Related articles:

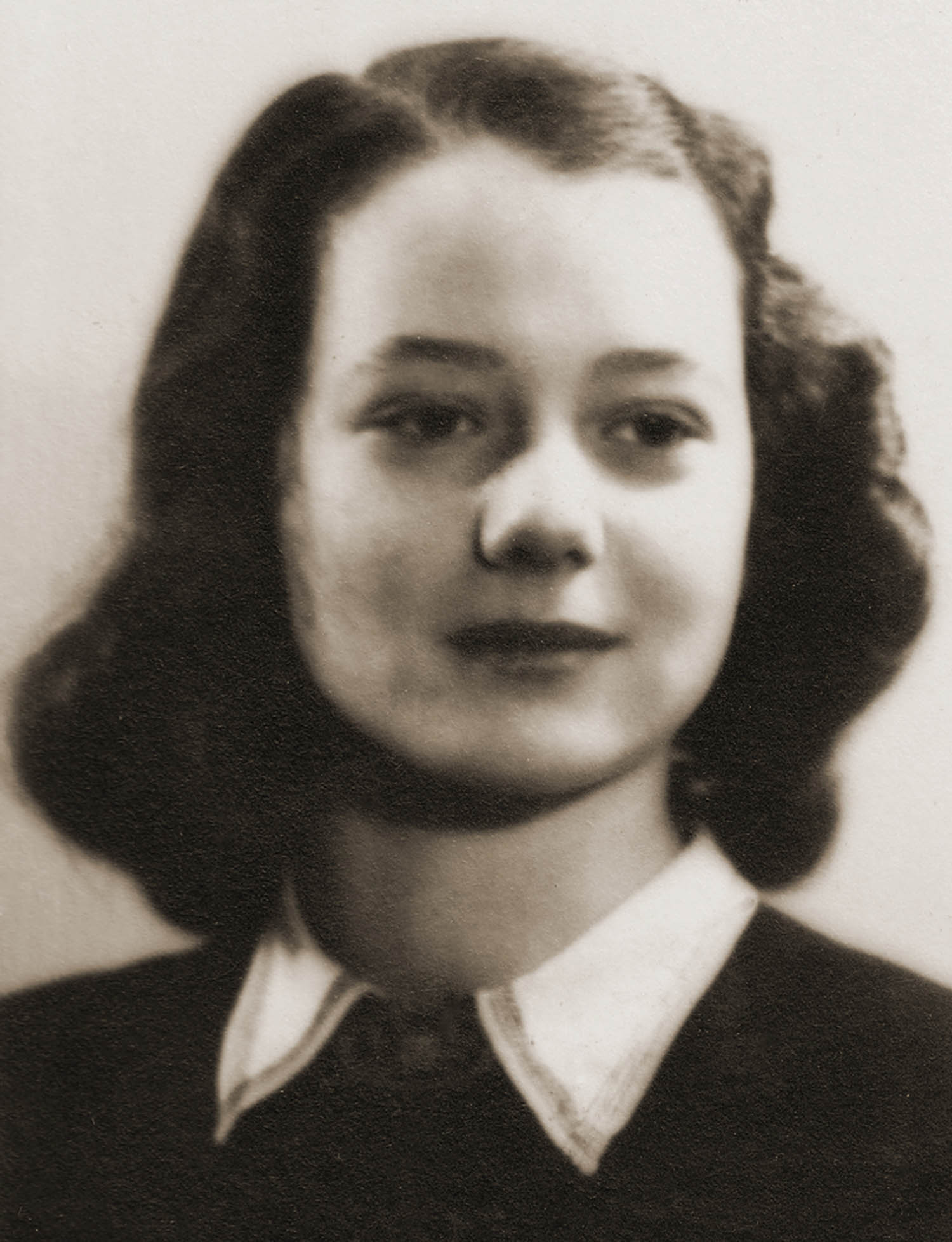

Kraus was born Edith Polachová in Prague in 1929. She didn’t know her family was Jewish until she was eight, shortly before Germany annexed Bohemia-Moravia in 1939 and her lawyer father was fired. Dita was sent to the countryside “until the storm blows over”. Three years later the family were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto where Hirsch organised sporting and cultural events, including an opera Kraus performed in. She was also taught art by Friedl Dicker-Brandeis and in later life in Israel loved to paint wild flowers.

The relative tranquillity of the ghetto was shattered in late 1943 when they were sent to Auschwitz.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“Despite the horrible conditions, we managed to hold on to a sense of dignity and purpose,” she said. “All that changed when we were transported east. The moment they shoved us on to those cattle carts was the moment we were totally stripped of our humanity.”

Her father died six weeks later.

After six months at Auschwitz, Dita and her mother were among 1,000 women and girls sent by Josef Mengele, the notorious Nazi doctor, to a work camp in Hamburg, then to Bergen-Belsen, which she described as far worse than Auschwitz. It “was a horrific killing machine”, she said: “I existed on the biological level only, devoid of any humanity.”

They both caught typhus and while they survived until the camp’s liberation, her mother died in June 1945, leaving Dita an orphan at 15.

Dita returned to Prague. While waiting for an ID card, she met Otto Kraus, whom she recognised as one of the instructors in block 31, though they had never spoken. They married in 1947 and moved to Israel two years later. She worked in a shoe repair shop on a kibbutz and later taught English. Otto became a writer, whose book The Painted Wall tells his own story of Auschwitz. He died in 2000.

They had three children but their daughter died at 20 of a liver condition and their eldest son at 60 having suffered a mental decline.

“There were almost no long periods of happiness and quiet and peace of mind,” Kraus said. Her main message to young people she spoke to as a Holocaust survivor was not to hate. In one interview, asked what she would do if she could live her life again, she said she would like to work in a museum reassembling broken pots. She said: “I love to put things together.”

Dita Kraus, teacher, writer and Holocaust survivor, was born on12 July 1929 and died on 18 October 2025 at the age of 96.

Photographs by Katerina Sulova/CTK Photo and A Wilhelmer/Terezy Tomášové