Related articles:

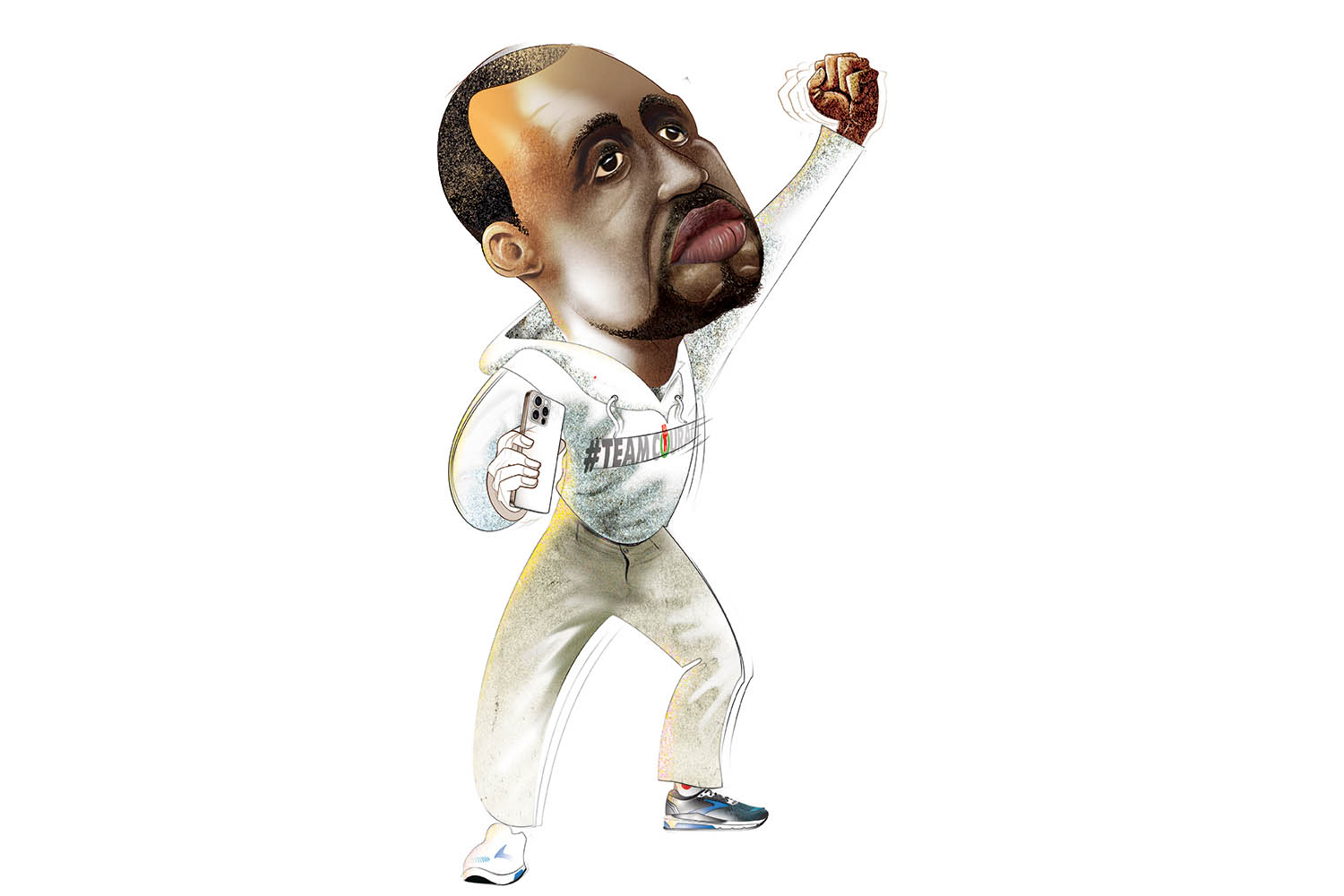

Illustration by Andy Bunday

Activism is a dangerous vocation in Kenya. Over the past two decades, Boniface Mwangi has been in and out of jail, charged with resisting arrest, unlawful assembly and contempt of court. His house has been burned down by armed men, he has been brutally assaulted and, at one point, his family fled abroad.

Not long ago, Mwangi likened himself to a “lone voice in the wilderness”. No matter how many protests he organised, despite all the stunts he pulled, there was no mass awakening of young Kenyans. No longer. In the past few years, the country has been gripped by huge waves of unrest led by young people organising online and fed up with high taxes, corruption and police brutality.

With his huge social media following – he has more than 2 million followers on X and 670,000 on Facebook – Mwangi has been at the forefront. In June, protesters took to the streets across the country, commemorating a demonstration a year earlier against a new finance bill. According to an Independent Policing Oversight Authority report released last week, 23 were killed. More than 40 died at another protest earlier this month. Hundreds have been arrested and the police carried out enforced disappearances, according to Kenya’s human rights council.

Mwangi was among those swept up in the crackdown. He was arrested last week, accused of the “facilitation of terrorist acts”. These charges were quickly dropped for lack of evidence. Instead he faces a lesser charge of possessing ammunition without a licence, after the alleged discovery of a blank round and three tear gas canisters during a police raid on his office.

His arrest was roundly condemned. Dozens of rights groups issued a statement saying Mwangi had been subject to a campaign that appears “to be part of a broader effort to intimidate lawful dissent”. Hussein Khalid, another prominent Kenyan activist, called the use of terrorism laws evidence that Kenya “has decided to follow the path of authoritarian regimes”.

When newspapers refused to publish his intense images of ethnic bloodletting, he took them on tour around the country

When newspapers refused to publish his intense images of ethnic bloodletting, he took them on tour around the country

Mwangi was still recovering from a brutal ordeal in Tanzania when he was detained. In May, he crossed into Tanzania with other activists to show solidarity with Tundu Lissu, an opposition leader who is facing the death penalty in a treason trial. He was apprehended at his hotel and taken to a compound where he said he was stripped naked and severely beaten and sodomised, before being dumped at the Kenyan border. Another activist was also sexually assaulted. Boniface chose to share the story, rather than be shamed into silence.

“Many of us were just shocked the [Kenyan] government would pick him up and plant charges on him so soon after that traumatic event,” says Kwamchetsi Makokha, a columnist for the Daily Nation newspaper. “But they are rattled and he is the most visible symbol of the protests.”

Related articles:

Mwangi’s activism runs through his life. The son of a single mother, whom he helped to sell books, he was expelled from his secondary school after he wrote to a minister protesting about its poor conditions.

But it was as a photojournalist that he first made his name during post-election violence in 2007-08. Kenya’s incumbent president, Mwai Kibaki, was declared the victor in a close and fiercely fought contest marked by evidence of ballot rigging. Raila Odinga, the main opposition candidate, rejected the result.

Boniface Mwangi

Born 10 July 1983, Taveta, Kenya

Work Photojournalist and activist

Family Hellen Njeri Mwangi, wife; three children

Subsequent months saw an eruption of ethnic bloodletting, stoked by politicians, that tore at the country’s social fabric and left more than 1,200 dead and as many as 350,000 people displaced. Mwangi documented the violence in Nairobi’s slums, where the fighting was most intense, taking pictures of beatings, lynchings and killings. In 2008, he won CNN Africa Photojournalist of the Year, an award he won again in 2010.

The international criminal court indicted several Kenyan leaders for the chaos, including Kenya’s current president, William Ruto, who was education minister at the time. The case was declared a mistrial “due to a troubling incidence of witness interference and intolerable political meddling”.

What Mwangi witnessed radicalised him. In 2009, he heckled Kibaki during a rally at a stadium celebrating Kenya’s national day and was promptly arrested. He also grew frustrated with newspapers after his editors refused to publish some of his images, saying they were too violent. Instead, Mwangi took them on tour in an exhibition around the country, hoping they would promote peace.

‘Before, activism was sending petitions. Boniface ratcheted things up in a very visual manner. He speaks young people’s language’

‘Before, activism was sending petitions. Boniface ratcheted things up in a very visual manner. He speaks young people’s language’

Kwamchetsi Makokha, Daily Nation journalist

Soon afterwards, Mwangi devoted himself to activism. With grants and money from selling his photography studio, he founded Pawa254, an “artivism” hub, quickly developing a knack for attention-grabbing protests.

During one, he poured out 1,000 litres of pigs’ blood and released several swine daubed with anti-government slogans outside Kenya’s parliament to illustrate the greed of the political class. Another saw hundreds of coffins burned outside the building. A third involved protesters marching through Nairobi holding polystyrene babies to symbolise the country’s immature politicians.

“Mwangi brought a new energy and imagination to the Kenyan activism scene, using tactics that shock,” says Makokha. “Before that, activism was sending petitions, reaching out to government officials. Boniface ratcheted things up in a very visual and graphic manner. He has a wide reach among young people because he can connect with them. He speaks their language.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In 2015, Mwangi’s activism helped stop a hotel allegedly linked to the Ruto family from building a car park over a school playground.

In 2017, he ran unsuccessfully for parliament. His campaign was modelled on Barack Obama’s. Rather than doling out cash to voters, as is customary for Kenyan politicians, he solicited small donations. The effort earned him death threats; he went around in a stab-proof vest.

In 2019, when Ruto accused Mwangi of being a drunk, Mwangi called Ruto a thief and a murderer, prompting Ruto to sue.

Throughout his campaigning, Mwangi has shown remarkable courage, says Makokha. “He’s somebody who feels all the cuts his country has suffered personally, and then he decides he’s going to do something about it.” That has made him the biggest thorn in the side of Kenya’s embattled government.