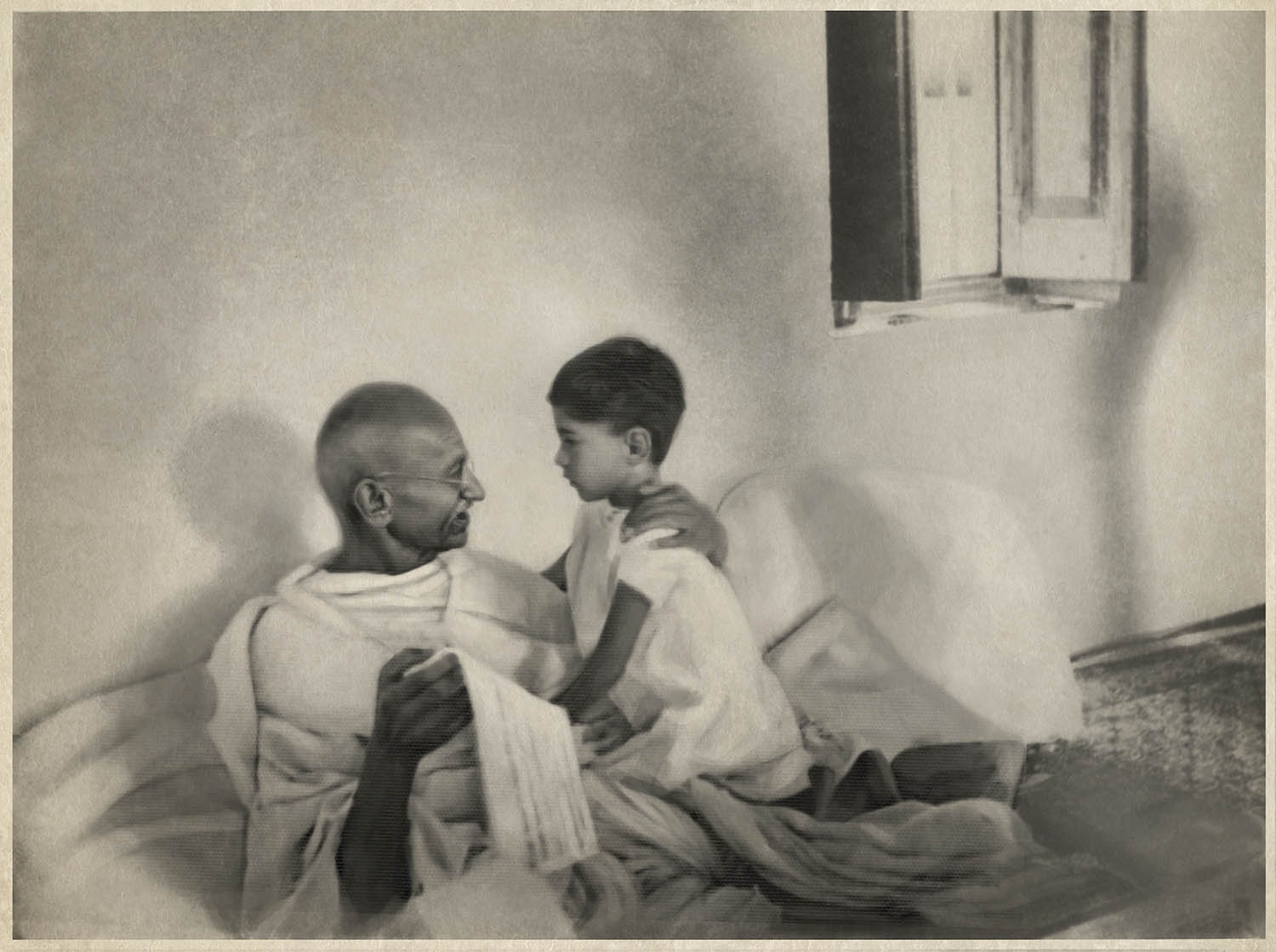

Mahatma Gandhi was not known for his hot head, yet he fully recognised the power of rage. “Anger to people is like gas to the automobile – it fuels you to move forward and get to a better place,” his grandson Arun Ghandi recalled him saying. “Without it, we would not be motivated to rise to a challenge … It is an energy that compels us to define what is just and unjust.”

Such views have not been widely shared by other great thinkers. The Stoic philosopher Seneca saw anger as a kind of madness, “loathsome and savage”. “Unlike other vices it does not tempt the mind but carries it off by force,” he wrote. It is indiscriminate, he claimed, bringing destruction “not only on the targets of its aim but on whatever happens to cross its path”.

The latest scientific research, however, sides with Gandhi. While unbridled anger can bring out the worst in human nature, it can also feed our motivation, strengthen our mental focus and drive our creativity. We just need to learn how to focus it in the right direction.

This much-needed reappraisal follows a growing understanding that all human sentiments, no matter how uncomfortable, serve a purpose, and recognising those benefits tends to bring greater wellbeing. In 2016, for instance, Gloria Luong, an associate professor at Colorado State University, and colleagues asked participants to rate various negative emotions – including anxiety and anger – for their appropriateness, utility and meaningfulness. Those who saw the good in their bad feelings enjoyed better health over the following weeks – independent of the life stress they were under.

Thinking differently about anxiety can help people shift their mindset about stressful events

Thinking differently about anxiety can help people shift their mindset about stressful events

There is now a wealth of evidence about how thinking differently about anxiety can help people shift their mindset about stressful events. When students are taught to view their nerves as a source of energy, they tend to get better grades. That’s because the increased physiological and psychological arousal that comes with stress can prepare us for sharper thinking – and by recognising this fact, we are better able to make use of it. Is it time for anger to have a similar makeover?

The earliest research in this area focused on the value of anger during negotiations. While few scientists would deny that violent outbursts are toxic, small flashes of anger are often necessary to show we are serious about protecting our rights – and by masking those feelings, we lose out. “It’s a bargaining emotion,” says Daniel Sznycer, an assistant professor of psychology at Oklahoma State University.

In 2006, scientists at Stanford University asked pairs of students to take the roles of a job candidate and a recruiter who were haggling over the benefits of a new position, such as salary. Half the students were told to hide their emotions, while the rest were encouraged to express their irritation through facial expressions, such as frowning, gestures such as banging their fists on the table, and tetchy declarations such as, “you’re really getting on my nerves now”.

Contrary to the idea that we should always keep a cool head in negotiations, they found that physical and verbal signs of frustration tended to bring better results. Anger was perceived as toughness and that led the other person to back down more quickly.

Such findings have been replicated many times. “There are lots of studies showing that expressing anger causes other people to concede,” says Heather Lench, a professor in psychological and brain sciences at Texas A&M University in College Station.

It turns out that anger is particularly important when defending our reputation and ensuring that people make the necessary reparations when they have hurt us. People with high emotional intelligence are already aware of this; they report actively cultivating their anger before a potential conflict. Szyncer emphasises that the key is to ensure that the intensity of our feelings is commensurate with the offence. “Escalation can be costly,” he says.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Clearly, the benefits of anger for negotiation can’t be an excuse for bullying; we must be careful to express ourselves appropriately. In some cases, it will also be logistically impossible to communicate our displeasure with the person who needs to hear it. Fortunately, there are other ways to channel our anger – as Lench’s experiments, published last year, show. In one study, she presented students with images designed to raise their hackles – such as a T-shirt insulting their home state, or graffiti stating “they suck!” over their participants’ college’s logo. They were then asked to solve difficult anagrams, framed as a “verbal intelligence test” – making a high score extremely very attractive. The puzzles were presented on a computer screen, and students were told they could move on to the next question any time they wished. Many gave up rather quickly, but the angry participants stuck with each word game for longer, resulting in a 39% higher score than participants who had viewed neutral images.

To see if indignation could fuel performance in other domains, Lench and her colleagues asked students to complete a ski slalom on a Nintendo Wii. Again, she showed them aggravating images, which helped them avoid many more red flags on the virtual slope. A third experiment involved a computerised test of reaction times, with a financial incentive for a better performance. In this case, the provocation was technical: the programme kept malfunctioning, which made it harder to win their prize. “We found people in this condition did respond faster and do better,” says Lench.

It’s easy to see how this response might be advantageous in sports. Researchers from the University of Virginia examined basketball players’ responses to “clear path fouls” – a dirty move against a player who has access to an unguarded basket, preventing them from taking a relatively easy shot. You might expect their irritation at the offence to have been a major distraction when they took their penalty “free throw”. In reality, their shots tended to be more accurate after clear path fouls compared to those awarded for less egregious or technical infarctions infractions – suggesting anger had fine-tuned their focus.

Lench’s research should give political strategists food for thought, since she has shown that anger can awaken dormant voters more effectively than other emotions. As part of long-term project examining people’s abilities to predict their emotional responses to events, participants were asked to imagine how angry, and how scared, they would feel if their candidate lost in the 2016 and 2020 elections. Analysing this data, Lench found the more anger someone anticipated feeling, the more likely they were to vote. Fear, in contrast, made no difference to their voting behaviour.

The effects of anger were not always desirable; Lench also found that angry participants were more likely to cheat on a test. “The idea is that anger motivates you to take action, but it might not always be the best thing,” she says. “We’re not saying anger is necessarily ‘good’ or beneficial, but that it can help you overcome obstacles.” Like any tool, we have to be careful how we use it.

Simply recognising anger’s effects can help us to keep it under our control, Lench says. “Instead of thinking that you’re a terrible person for feeling angry, it’s important to stop and recognise that it is an important signal.” In most cases, your anger will be telling you that some goal or value is being challenged, so it’s worth spending a few moments identifying exactly what it is that you want to achieve. This should prevent you from acting too rashly, so that you can use your energy to enact positive change.

Imagine your spouse has forgotten to say they’ll be late from work, when you were meant to go on a date. One reaction might be to choke down your resentment and pretend nothing is wrong. Another might be to lash out. At the heart of the issue, however, might be the sense they were taking you for granted, and disappointment that you couldn’t share the evening with them – ie you want the relationship to improve. And you can only do that through a respectful conversation that expresses your feelings without causing more hurt. An experiment – currently awaiting publication – by Karina Schumann, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Pittsburgh, shows the power of this approach. Couples were given advice on putting their conflicts into perspective by articulating their broader values and questioning how they related to a conflict. Almost immediately they had more constructive conversations – and the benefits for their relationship satisfaction could be seen a year later.

With politics, we might argue with our families or rant online, but we might ask whether there are better ways to spend our passion – such as campaigning for causes we care about and volunteering for organisations that are attempting to bring about the change we desire.

This was the lesson Mahatma Gandhi taught his grandson. “When we channel electricity intelligently, we can use it to improve our life, but if we abuse it, we could die,” Arun Gandhi wrote in The Gift of Anger. “So as with electricity, we must learn to use anger wisely for the good of humanity.”

Photographs Ali Matin/AFP via Getty Images, Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images, courtesy of Arun Gandhi, Leif Skoogfors/Getty Images

The Laws of Connection: 13 Social Strategies That Will Transform Your Life by David Robson is out in paperback (Canongate) on 5 June