This time last year, Australian captain Pat Cummins published a book, Tested. In that pleasing way he has of doing things a little differently, it was not your conventional mid-career autobiography, but 11 highly-polished interviews with various public brand names, from sport to science, politics to podcasting, in a broadly affirming, life-lessony vein.

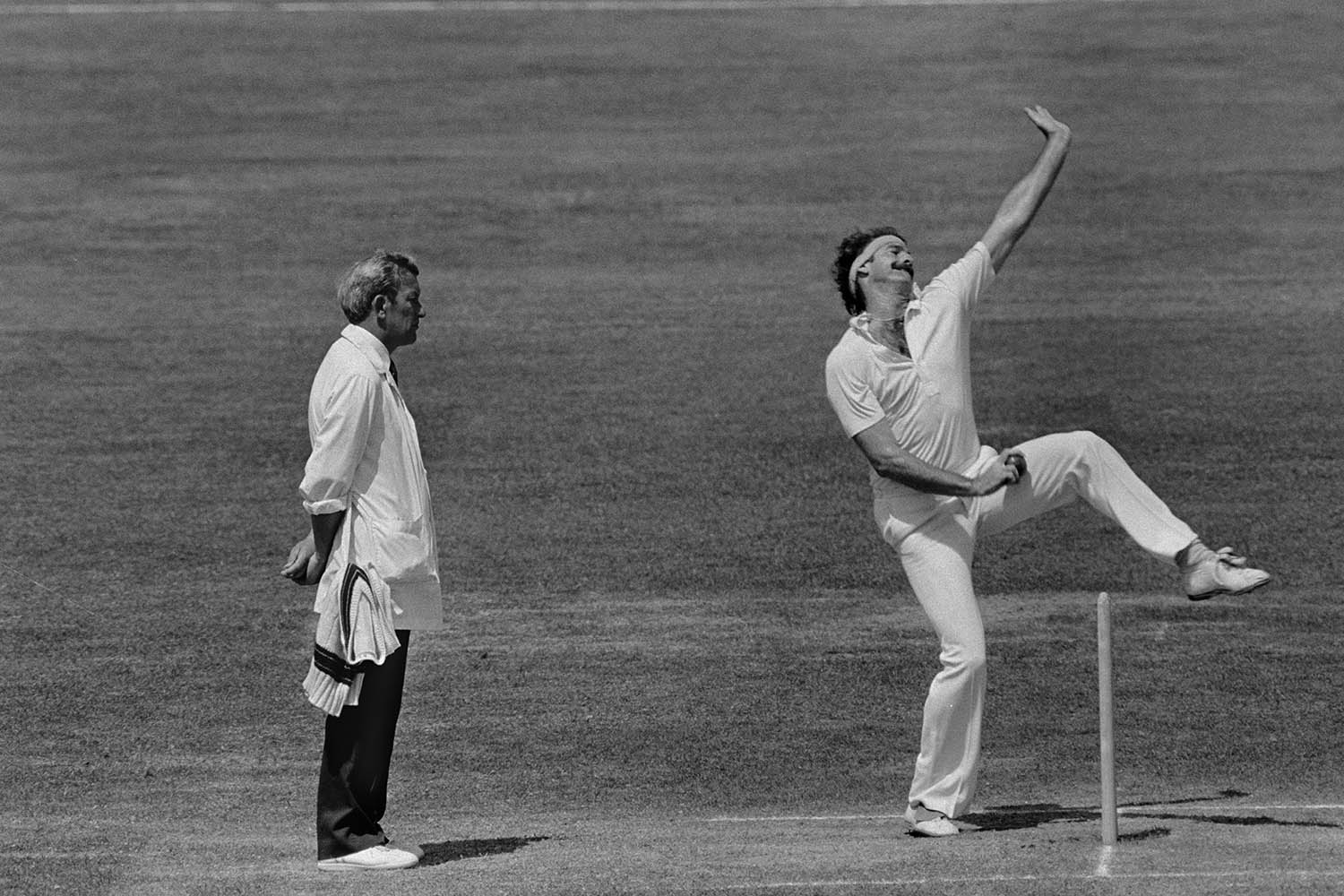

The only cricketing eminence among them was acutely chosen. Cummins identifies Dennis Lillee as an inspiration and a pathfinder. Like Cummins, Lillee was the embodiment of the tearaway; like Cummins, he surmounted a career-threatening injury. The pair linked up during Cummins’s rehabilitation between 2012 and 2017. The younger man credits his elder with adjusting his action just enough to ease wear and tear without sacrificing bodily autonomy. The prior friendship makes for an excellent interview, and an intriguing accompaniment to Cummins’s new dilemmas.

For Cummins has now succumbed to the same baleful affliction as Lillee half a century ago. Back then, vertebral “stress fractures” were seen as a fancy name for a sore back. “A lot of people thought I was staging it,” Lillee told Cummins. “Then they’d just tell you to stop bowling for a few days and try again. When it got worse they’d give you the horse needle, which was steroid injections I guess.” When his back packed up completely, Lillee spent six months in a plaster corset, and a year in a famously furious, self-directed and self-funded campaign to forge his path back.

The treatment of stress fractures are now the subject of a great physiotherapeutic industry and a voluminous literature. The “hot spots” that anticipate fractures, such as those diagnosed in Cummins, are understood as unavoidable to fast bowlers as callouses are to blacksmiths. But the human body has not changed so much, and their counteraction takes time, with the result that Australia’s captain has not bowled a ball in three months and seems little closer to doing so barely six weeks from the Ashes.

It makes sense too. Cummins is in his 33 year, and stands 6ft 3in – the older and the taller you are, the slower you heal. He has also been extremely blessed, playing 70 Tests of Australia’s last 78, plus 62 one-day and 39 T20 internationals over the same period, not to mention his labours for three Indian Premier League franchises.

For eight years, his broad back and bow-legged run have been a guarantor of Australian quality; for the last four, his low-temperature leadership has spread calm through the Australian team. He has so seldom fallen short of his standards that those moments stand out, and a shabby opening spell at Nagpur and a wretched shot at Delhi in 2023 were lent poignance when it emerged that Cummins’s mother was in the last stages of terminal illness, whereupon he hastened to her bedside. But to paraphrase a popular science title, an athlete’s body keeps the score, and sooner or later it adds up.

All this might have happened last season, when Cummins bowled more than 1,000 deliveries in the Border-Gavaskar Trophy, not to mention contributing match-winning runs in Melbourne. In the event it was Jasprit Bumrah who succumbed to injury, Australia outlasting rather than outplaying him.

The Australian hierarchy, perhaps sensing how close they were running their skipper, excused Cummins the tour of Sri Lanka and the Champions Trophy. But they could not stand in the way of his pulling $2,14m as captain of Sunrisers Hyderabad at the IPL, an event for which mountains would be flattened and rivers diverted. The bank balance keeps the score too.

All of which leaves an indeterminate hole in Australia’s Ashes plans. Cummins might yet figure, but he is unlikely to be ready in time for the day Test in Perth, where his pace might have been determinative, and also possibly the night Test in Brisbane, where his pink ball prowess (33 wickets in five outings) would have been on show. He is important enough effectively to need two replacements, likeliest to be Steve Smith as captain and Scott Boland as bowler. Each is 36, which does tell a tale about Australian cricket as presently constituted.

Smith has had the field-marshal’s baton in his knapsack since returning after Sandpapergate. He has stepped in for Cummins on half a dozen occasions, winning five Tests and contributing meritoriously with the bat. Interestingly, the same day that The Age heralded Cummins’s potential unavailability, the newspaper also reported that Smith was being considered for the No3 position in Australia’s disorderly top order. He averages 67 in the role, even if the data is dated and the kite might yet be yanked to earth.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Boland’s cardinal virtue, meanwhile, has always been fitness. Australia’s next generation of pace bowlers, not unlike England’s, has a propensity for long absences with injury – Lance Morris, Jhye Richardson, Brendan Doggett and Spencer Johnson are all sidelined at present. Boland, thanks to his energies not being diffused in white-ball cricket and a physique that looks like it could tow a plough, is ever ready: he stepped in manfully last season, when injury deprived Australia of Josh Hazlewood, taking 21 wickets at 13 in three Tests.

Dennis Lillee bowling during a match, July 14th 1981.

In Perth, however, Boland would on present indications form part of a combination with Hazlewood (34), Mitchell Starc (35) and Nathan Lyon (who turns 38 on 20 November). It’s a vintage era for sequels, of course. But how you regard the present Australian team might depend on whether you prefer Top Gun: Maverick or Spinal Tap II: The End Continues.

Advantage England, then? Of course. Cummins’s edge on key English batters, notably Joe Root, has been a leading indicator of Australian supremacy in the last four Ashes series. It is also a natural hazard for captains that bowl, which has been an argument against them, even if batters get injured too, and the antecedents are quaint.

You must look back to 1961 for an Australian precedent, when the physical fates conspired against Richie Benaud during an Ashes in England, eliciting Ray Robinson’s decorative line: “An obstinate tendon injury made his shoulder the most discussed since the Venus de Milo’s.” The Australian optimist can point to Benaud bouncing back with an Ashes-winning six-for at Old Trafford, and observe that Ben Stokes by his body-and-soul commitment runs many of the same risks as his counterpart.

Cummins’s position comes with further context. In their simpatico conversation in Tested, Cummins spends a lot of time traversing Lillee’s involvement in World Series Cricket - the last occasion on which private capital made deep inroads into Australian, and global, cricket.

“They thought we were being selfish and chasing a dollar,” he quotes Lillee as saying. “That was how people saw it….A lot of people owe Kerry Packer a debt. He was a great man.” Cummins concludes in echo: “I think the players, the game and the fans are now all much better off for it.” Cummins sees the lesson as “it’s important that we continue to improve the sport for those in the future”.

Coincidentally the other Cummins headlines of last week here involved him having recently received an “informal” offer of $10m a year simply to play franchise cricket, which he “politely rebuffed” - it’s hard, of course, to imagine clean-cut Cummins rebuffing anything impolitely.

Such gossipy stories, growingly familiar in the media here, are primarily in service of the case for Australian cricket embracing external investment - a “there is no alternative” narrative long beloved of player managers, but increasingly emanating from Cricket Australia. As goes The Hundred, runs the argument, so must go the Big Bash League; beware the sports-industrial complex, runs the counterargument, whoever the modern Prince Kerreed bin Packerina al Saud or his equivalent turns out to be.

Every athlete experiences injury as an intimation of mortality. Life is long; sport is short; needs must. A 32-year-old father of two with more peak earnings years behind than ahead would be tempted by an eight-figure cheque anyway; the more so, perhaps, if he was persuaded that this aligned with a perceived duty to “continue to improve the sport” by making it safe for capital. This is a longer game even than the Ashes.

Photographs by Tom Jenkins/Getty Images, Dennis Oulds/Getty Images