“I don’t know about you but my emotions are up and down all day.” Pale, perceptive blue eyes pierce through Mark Phillips’s soft features as he nurses a turmeric latte. “For the last week I think I’ve cried every single day. It’s good to understand that’s probably because you’ve done too much, you’ve not done your own self-care routine.

“As I learn more about my ADHD, I want to learn about how it represents in my life, and to master it and hone it to be a positive but also accept and be compassionate about myself, that actually it is normal for me to be sad in a day, to maybe feel like I’m gonna cry, and that’s okay, and so to be kinder to myself.”

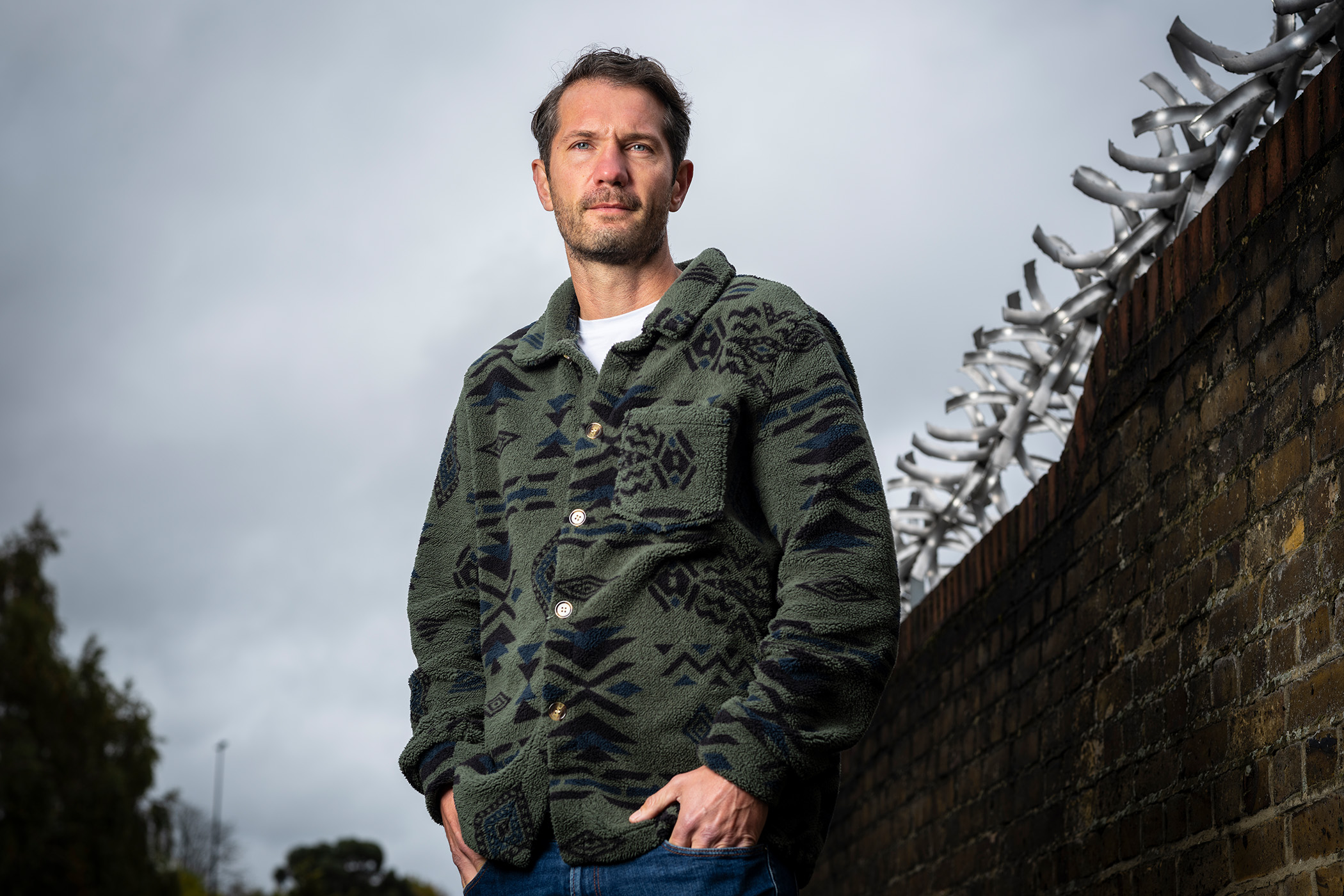

A Millwall academy graduate, Phillips grew up first in Brockley and then Bromley, a few miles from the Greek coffee shop we meet in on a tempestuous Thursday. Injuries meant he played just 67 league games across eight years at Millwall, before spending two years at Brentford, which included winning League Two in 2008-09. In hindsight, years at Southend from 2010 to 2014 were probably the happiest of his career, winning 2012 player of the year in and reaching the Football League Trophy final the following year. From there, he gradually slid down the pyramid until retiring at Kingstonian in 2019.

Now 43 – achingly, charmingly sincere and kind – retirement has been tougher than football ever was, enduring a “very hard” divorce and his father’s death just a month after being diagnosed with motor neurone disease. Then, earlier this year the second-eldest of his four kids was diagnosed with ADHD after trouble at school. As he researched to help his son, he reflected on his own life and mind.

“I was in quite a negative place about how I saw myself, my self esteem was rock bottom,” he explained. “Why couldn't I focus on one thing? Why can’t I complete that task? Why did I avoid the mundane things?”

“Then I was seeing these things about how [people with ADHD] compare yourselves to others, how you have constant ideas but you can't execute them because of your organisational skills, your emotional regulation, how you feel things very deeply. And it was just all making sense.”

He pursued an ADHD diagnosis of his own, confirmed in March.

“It was probably up there with one of the best moments of my life,” he said.

“It gave me the most optimism and hope for years, particularly since the end of my career. Everything made sense in my life – I wasn’t broken, there was nothing wrong with me.” He has also been told he displays autistic traits but has not been formally diagnosed.

And since his diagnosis, he has not stopped thinking about neurodivergence. He took six months to learn everything he could about ADHD, reading constantly – the first time he really remembers being able to finish a book – and speaking to anyone who would talk to him. But over the past month, he started playing offence. He has discussed his diagnosis on the BBC, Sky and talkSPORT – partly inspired by Lucy Bronze’s similar announcement – launched neurodiversity advocacy site The ND Footballer, recorded meditations specifically designed for the ADHD brain, and tried float therapy. Emotional burnout is an understandable occupational hazard.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Despite research suggesting 15 to 20% of the population are neurodivergent, Phillips is still one of fewer than 10 current or former professional men’s footballers to have disclosed their ADHD diagnoses publicly – others include Charlie Austin, Ravel Morrison, Jermaine Pennant, Dean Windass and Tim Howard. No player has ever revealed a diagnosis while still playing in the Premier League or Championship, despite an ongoing Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) survey of 700 players suggesting 5% have been formally diagnosed with a neurodivergent condition like ADHD, autism, dyslexia or OCD. 26% also said they struggle with attention and focus, while 22% reported issues with social interactions.

But while Austin and Windass have admirably discussed their diagnoses at length, Phillips is comfortably the most knowledgeable and enquiring about football’s neurodiversity crisis. No footballer has ever spoken about it with this expertise and passion, with such clear, achievable goals, but he is careful to avoid stereotypes.

“I don’t like to use the word superpower, because there is a real negative side to this condition,” he said.

“But equally it is a huge strength if you can tap into it. I’ve got to start forcing conversations, because it’s so obvious. Football is evolving. Managers are more aware of the individuality of players and how to get the best out of them.

“There are neurodivergent players, staff members, managers. In a sport that is perfectly suited to neurodivergence, there’s going to be high numbers.

“It makes complete sense that we understand each and every individual's drivers, what motivates them, what could have a detrimental effect on their performance. It’s just simple man management.”

As Phillips mentions, professional football lends itself to neurodiversity, particularly ADHD: a well-enforced and maintained structure and routine, almost constant exercise, ever-changing targets and stimuli. Equally, some ADHD traits lend themselves to elite football – the ability to think quickly and act under pressure, an innate creativity, hyperfocusing on your passions helping to inspire the requisite work to break the 1%. But perhaps the greatest challenge is not the football but the life it can facilitate away from training and matches.

“I really see the benefit in diagnosis and people becoming more aware of it,” he said. “But equally, there’s a broader picture because we're talking about football players. They spend a minimal amount of time on the training pitch, in that environment.

“What are the clubs doing to be aware of their life outside of football? I wasn’t really understood in my relationships, so as a neurodivergent person, this could be affecting their lives. You might be happy as Larry on the pitch, but what’s actually behind it, because we’re very good at masking [suppressing or mimicking behaviours to appear more neurotypical].

“I call myself a professional masker, because I know how to act in certain situations, but I feel very awkward and very self-aware – which are things everyone feels, but mine’s times 10. I’m not asking for the world here. It’s just that understanding, awareness that there can be difficult moments.”

Diagnosis has forced him to reconsider every aspect of his life. The clearest example he can find is the gym – he has always loved exercise, but found weights boring and repetitive.

“Mark, why are you going to the gym? Are you going for you? Or are you going for what you feel you should be doing, to look how you feel you should be looking on Instagram? Because this is what people find cool?

“I felt looking back on my life, I had become so many different characters to fit in, rather than being my true self, which in the male environment of football would have left me very vulnerable.”

Across two hours together, Phillips’s mind is constantly sparking and fizzing in all directions, impossible to keep on the question, a Tommy gun of fascinating tidbits. One is that in his Player of the Year campaign at Southend, he had started rewatching clips of himself: “It would remind me how good I was as a footballer, and so I would go out on the pitch really confident.” Until then, he had been wracked by negativity, always focussing on the next game and never taking time to reflect.

Another is how much rejection sensitivity – a common ADHD trait – impacted him. He found not being provided any explanation for being dropped torturous and damaging. He sobbed having been told he wasn’t going to start in the EFL Trophy final after working to recover from a broken foot. Twelve years on he still asks not to give the manager’s name airtime.

Injuries restricted and defined his career, a divine injustice for which he is still seeking explanation. There are proven links between ADHD and joint hypermobility, while the physical impacts of the psychological burden of neurodivergence are still under-researched.

“I’m now speaking to doctors who say the biological effects of neurodiversity on your body are becoming really apparent,” he said.

“How much tension did I hold in my body from that stress and worry that I put on myself? If you’ve got a player who’s neurodivergent, you have to, as a medical team, know how that will affect them biologically, and how that would impact them on the pitch physically, because the body and the mind are not two separate things.”

Since retiring, Phillips has run the 6occer Academy in Bromley, coaching around 400 kids every week and working with the Brit School. This has led him to examine the impact of neurodiversity on academy and grassroots players, a process he is only just beginning.

“How could an eight, nine, 10, 15-year-old be affected? They don’t know what emotional regulation is,” he said.

“They don’t understand why they’re feeling frustrated. It’s just that patience of maybe going and sharing a story with them, asking do you need a little moment? Just telling people it’s okay. You don't need to cuddle them and wrap them in cotton wool – it's literally just saying it’s okay, and understanding.

“That is my driver, really – when I see another neurodivergent person and you see their face light up when you say something, when they understand there's someone else like them. I’m not alone. It feels very lonely at times being neurodivergent, keeping these things to yourself. And so when you connect with someone, it's like gold dust. I found the same with my son.”

The PFA have said 60% of the surveyed players who display neurodivergent traits have not disclosed them to their club. Over the past six weeks managers, coaches, current and retired players have reached out to discuss both their diagnoses and feelings, and also how Phillips can teach them to help. There is a dam here waiting to be busted. Phillips might be the first ex-pro with the requisite balance of expertise and experience to do so.

“In the short term, there’s lots of people doing awareness, but it’s actually understanding what the reality is,” he said.

“The medium-term goal is working for more organisations and seeing how we can develop more in football, in terms of workshops for academies and also start asking questions in the game, but also after the game.

“When you come out of football, yes, there’s a broader theme that lots of footballers struggle. But equally, what does that mean? Because we are struggling for different reasons, not just because football's been taken away.

“There’s a lot of neurodivergent players who only become aware of that after they're playing. For me, football was an ADHD management tool.”

Although he was helped by Sporting Chance after retiring, the PFA have provided specialist neurodivergence counselling since his diagnosis.

“Knowledge of your neurodivergency is the most useful thing, because when you're really feeling anxious or down, you can get caught in negative thought loops,” he said.

“It’s really useful to know that this is not the reality, and you’re the priority. Knowledge is power.”

Photograph by Antonio Olmos for The Observer