If there is genius in Helen Lewis’s book The Genius Myth it’s in the choice of subject, and I wish I’d thought of it myself. Though had I done so, I wouldn’t have described the work of James Joyce as “what-if novels but harder to read” – and I would certainly have made plenty of room for sport.

The thing about genius is that it’s easier to find an example than a definition. One certainty: in sport at least, high achievement is not the same thing as genius.

The first name many people would place in the genius top 10 would be Shane Warne. But they wouldn’t consider his equally brilliant team-mate Glenn McGrath. Warne was a leg-spinner and he could make a cricket ball do things that seemed impossible.

His first ball in Test cricket in England, bowled to Mike Gatting, achieved the status of legend almost before it pitched: whereupon it hung a left and hit the off-stump, leaving poor Gatting looking like a muggle at Hogwarts. The illusion of magic is one of sport’s eternal delights.

McGrath and Warne are both in the top 10 all-time Test match wicket-takers, but McGrath’s talent was for accuracy and relentlessness. He lacked the magician’s aura. He also lacked the backstory of the reformed rapscallion; we like a genius to be picaresque.

Roger Federer is another automatic selection to the genius list, even though he’s only third on the list of all time male grand slam champions. But he, far more than Rafael Nadal or Novak Djokovic, made tennis look like magic. His ability to create apparently impossible angles made him the most compelling of the great three.

Above all, Federer was able to create the illusion of complicity: to make it look as if his opponent was actively contributing to the spectacle: conspiring in his own defeat for the love of beauty.

Johan Cruyff never looked like a footballer. He looked like a man who had just written a very important (and hard to read) European novel. On the field, it often seemed that he was operating in slow motion while all around him were in the most desperate hurry: the illusion of relative speed. And he was still greater conceptually. He made the glorious notion of Total Football actually work. It’s the best possible system but you can’t do it without Cruyff. As a manager he created the football of possession, subtlety and skill: the style that has dominated ever since.

Can a boxer be a genius? Can there ever be magic in just punching people? If so Muhammad Ali was a genius, one acknowledged from his very earliest days, at least by himself. And his story, the politically oppressed fighter who didn’t have nothing against them Vietcong and was still champion three times over: that has all the poetry a genius-hunter could wish for.

Ayrton Senna could do things with a racing car that no one else would dare: he could take a car out on a soaking track and drive flat out where the rest would barely tiptoe.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The traditional mythology of genius has rightly evolved over the years in sport and other canons

The traditional mythology of genius has rightly evolved over the years in sport and other canons

He participated willingly in the illusion that he was a man specially chosen and set apart from the rest. This myth was only reinforced by his death – his martyrdom as many saw it – on the track at Imola in 1994. All the above would effortlessly make anybody’s genius list.

You might add Ronnie O’Sullivan, recalling his maximum break in five minutes and eight seconds, Lester Piggott and his ability to get horses to perform beyond their normal capabilities, or Kevin Pietersen changing a match and a series in an hour of mayhem.

But these examples are somewhat male and more than a little white. The traditional mythology of genius has quite rightly evolved over the years in sport and in other canons. Muttiah Muralitharan took more wickets than Warne and was just as brilliant. So why is he less celebrated? A quieter personality, perhaps, the fact that he is Sri Lankan rather than English, Australian or Indian, and certainly the disobliging nonsense from Australians who cultivated – against scientific evidence – the belief that Muralitharan was a chucker.

Malcolm Marshall was a genius of terror, but the conventional view of genius prefers spin bowlers to the super-quicks. Why so? I saw Marshall bowl in a plaster-cast at Headingley in 1984, scrambling the wits of the England batters with this speed and ferocity, dismissing three.

The following Monday in changed conditions he cut his speed, got extravagant lateral movement and took another four.

Simone Biles has five gymnastic skills named for her, most of them beyond the scope of any of her rivals. That in itself is worth the name of genius, but the arc of her story makes her achievements still more vivid: four gold medals at the Rio Olympics of 2016, telling the world about her abuse by the unspeakable Larry Nassar, and then suffering from potentially lethal self-doubt at Tokyo before coming back in Paris to win three more golds. And Martina Navratilova changed women’s sport with her radical approach to preparation and physical fitness, especially her use of cross-training, borrowing from disciplines outside her chosen sport. This revolutionary approach won her 18 grand slam singles titles.

The allure of genius is as much about myth-making as about achievement. It is invariably a personal decision rather than an objective assessment. Philosopher and media theorist Marshall McLuhan said: “Blast the sports pages! Creators of pickled gods and archetypes!” But we who watch sport have a strong taste for archetypes and the archetypal genius is an important form of pickled god. We like the idea of special people, people marked out by the almost incontinent nature of their talent – especially if they come with a powerful narrative and an expansive personality.

All these geniuses polished their auras, not for vanity but as a weapon: for sport is about beating other people. But the athletes we call genius seem to play as if there were more important matters in life than mere victory. Perhaps genius in sport can be defined as the athletes who, in seeking victory, create the illusion of art.

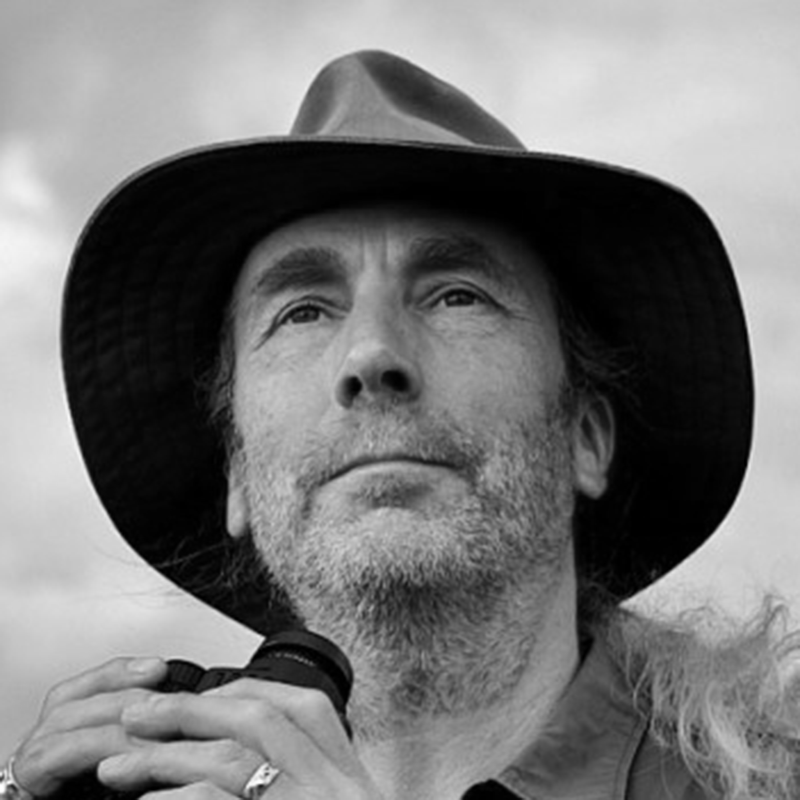

Photograph by STF/AFP via Getty Images