As Victor Osimhen paced around the pitch, stamping his feet and shaking his head and angrily brushing off his teammates’ attempts to placate him, Nigerian football found itself presented with a Rorschach test. From one angle, the striker’s undisguised fury appeared a perfect encapsulation of the national team’s chronic ills. From another, it could just about be seen as a solution to them.

The source of Osimhen’s “frustration”, as he would describe it, was obvious. His team had just conceded a last-minute equaliser against Zimbabwe, marking the third successive home game Nigeria had failed to win. “We should have won,” Osimhen said, a few days later, looking back on his reaction. “We had the lead. We controlled the game. And then just like that, we let it slip.”

The consequences may well be severe. The draw left Nigeria fourth in their World Cup qualifying group, not only trailing South Africa but behind Rwanda and, even worse, its next-door neighbour, Benin, too. Just four games remain; only the group winners are guaranteed a place in next summer’s finals. “At this point, you have to say it is very unlikely Nigeria will qualify,” the Nigerian writer Osasu Obayiuwana said.

The structure of qualifying, certainly, appears to be weighted against them. To make it, Nigeria do not just have to win all of their own games, but hope results across the continent go in their favour; even then, their reward might be the chance to win a playoff to get into another playoff.

The squad, of course, remains bullish: Alex Iwobi, the Fulham midfielder, made clear this week that “as players, we still believe.” But then they have little choice: the alternative is borderline unthinkable. Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country. Its team is, as Osimhen said earlier this year, “packed with stars from the top leagues in Europe.” The country sees itself as the continent’s true footballing superpower. Failing to reach an expanded World Cup, one that will include at least nine African teams, would rank as a national humiliation.

Attempting to establish where responsibility lies for that looming catastrophe is not, on the surface, especially hard. Africa’s qualifying programme started in November 2023. Since then, Nigeria have played three pairs of games. They have had a different manager for each set, starting out under José Peseiro, an experienced, peripatetic Portuguese coach; enjoying a tumultuous whistle-stop visit from Finidi George; and finally experiencing something like stability with the incumbent, Éric Chelle. The lack of direction – what Obayiuwana regards as the “incompetence of those appointing the managers” – runs much deeper than that. Peseiro left just a few months after he and his squad were named as Members of the Order of the Niger, one of the country’s highest honours, for their performance in the African Cup of Nations.

George, one of the heroes of the national team that qualified for the World Cup in 1994, handed in his notice after learning in the media that the Nigerian Football Federation wanted to import a technical director above him. He was so blindsided by the announcement, he said, that he had to “pull over to the roadside to read about it.” He submitted his resignation almost immediately. George was supposed to be replaced by Bruno Labbadia, a stalwart of sundry Bundesliga technical areas, but the German removed himself from consideration because of “various organisational issues.” Augustine Eguavoen, the federation’s technical director, stepped in briefly before Chelle, a significantly lower-profile, cheaper option, took the permanent post.

“Something drastic must be done,” Sunday Oliseh, another icon from that 1994 team, said earlier this year. “If Nigeria does not qualify for this World Cup, and the people running football in Nigeria are still in their positions, then we do not even deserve to qualify for the one [after that].”

Related articles:

Unapologetically outspoken, Oliseh has emerged as an all-purpose critic of the shortcomings of his heirs in the national team, railing not only against organisational failures but the country’s tendency to name captains who are not necessarily first-choice players. Those decisions, he said, serve to outsource the job of leading the team on the field to mere “assistants.”

He is not the only one to place at least some blame for the team’s struggles on the players themselves. Chelle’s squad for this week’s qualifiers – against first Rwanda and then South Africa – includes seven Premier League players, as well as Osimhen, Ademola Lookman and Wilfried Ndidi.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

As Moses Simon, one of the team’s mainstays, pointed out diplomatically earlier this week, this is the first time during qualifying that Nigeria have been anywhere close to full strength.

The federation, last year, was rather more direct, releasing a statement expressing their “displeasure with the poor attitude of some of the players to the national assignment.” It is a sentiment that John Obi Mikel, the former Chelsea midfielder, has hinted at, too, when he suggested that there was a tendency for players drawn from the Nigerian diaspora to see representing the land of their parents’ or grandparents’ birth – rather than England or France – as a “second option.”

That tension is what made Osimhen’s fury a perfect inkblot: he was both demonstrating the cosseted petulance of Nigeria’s underperforming stars and the understandable frustration of players let down by those in positions of power above them.

Either way, of course, the outcome is the same: a giant brought low by its own failings, overtaken by teams it would not typically regard as its equals. “If you look at a lot of the smaller countries, they have made the most of what they have, the maximum from the minimum,” Obayiuwana said. “Nigeria is the opposite. We should have everything, but we have made the minimum from the maximum.”

The 2026 World Cup – who is on the verge and who is at risk?

Ecuador

South America has a new third force: thanks to a golden generation of players, led by Chelsea’s Moisés Caicedo and the new Arsenal signing Piero Hincapié, Ecuador have not only qualified for a second straight World Cup, but they are currently ahead of Brazil in the standings. La Tricolor have only made it out of the groups at the finals once before – in 2006 – but Sebastian Beccacece’s team carry such a threat that expectations for next summer run significantly higher.

Venezuela

The only South American nation not to have qualified for a World Cup, Venezuela’s hopes of ending their long wait are hanging by a thread: an automatic spot looks beyond them, and they may have to beat either Argentina or Colombia to claim a place in the intercontinental playoffs. Given the country’s volatile political situation, that in itself would be a remarkable achievement.

South Africa

Bafana Bafana have only qualified for the World Cup once before, in 1998, and have not featured in the tournament at all since hosting it in 2010. Hugo Broos’s team, almost exclusively comprising players from the country’s top flight, need only hold their nerve to change that. They have lost just once, away in Rwanda; two wins, from their four remaining games, should do it.DR CongoThe country’s playing resources have been bolstered considerably in recent years, thanks to a concerted attempt to tap into the Congolese diaspora. As a result, the team contains a host of familiar names – Aaron Wan-Bissaka, Arthur Masuaku, Jeremy Ngakia, Yoane Wissa, Axel Tuanzebe – and is currently on course to qualify for the country’s first finals since 1974 (when it competed as Zaire).

Uzbekistan and Jordan

Things appear to be changing in Asia. Most of the continent’s traditional heavyweights will be in North America last summer – only Saudi Arabia have yet to confirm their place – but so too, for the first time, will Uzbekistan and Jordan. Uzbekistan are not quite as inspired by Manchester City’s Abdukodir Khusanov as might be imagined; the former Roma striker Eldor Shomurodov is the country’s talisman. If anything, Jordan becoming the first side from the Arab world to qualify this time around is even more remarkable.

And on the other hand, Italy…

It is very difficult to work out what is going on with the Italian national side. They missed out on both the 2018 and 2022 World Cups, both failures a source of intense embarrassment, and yet somehow managed to win the European Championship in between. Having already lost heavily to Norway this time around, Gennaro Gattuso’s team essentially now have no margin for error if they wish to avoid a third consecutive humiliation.

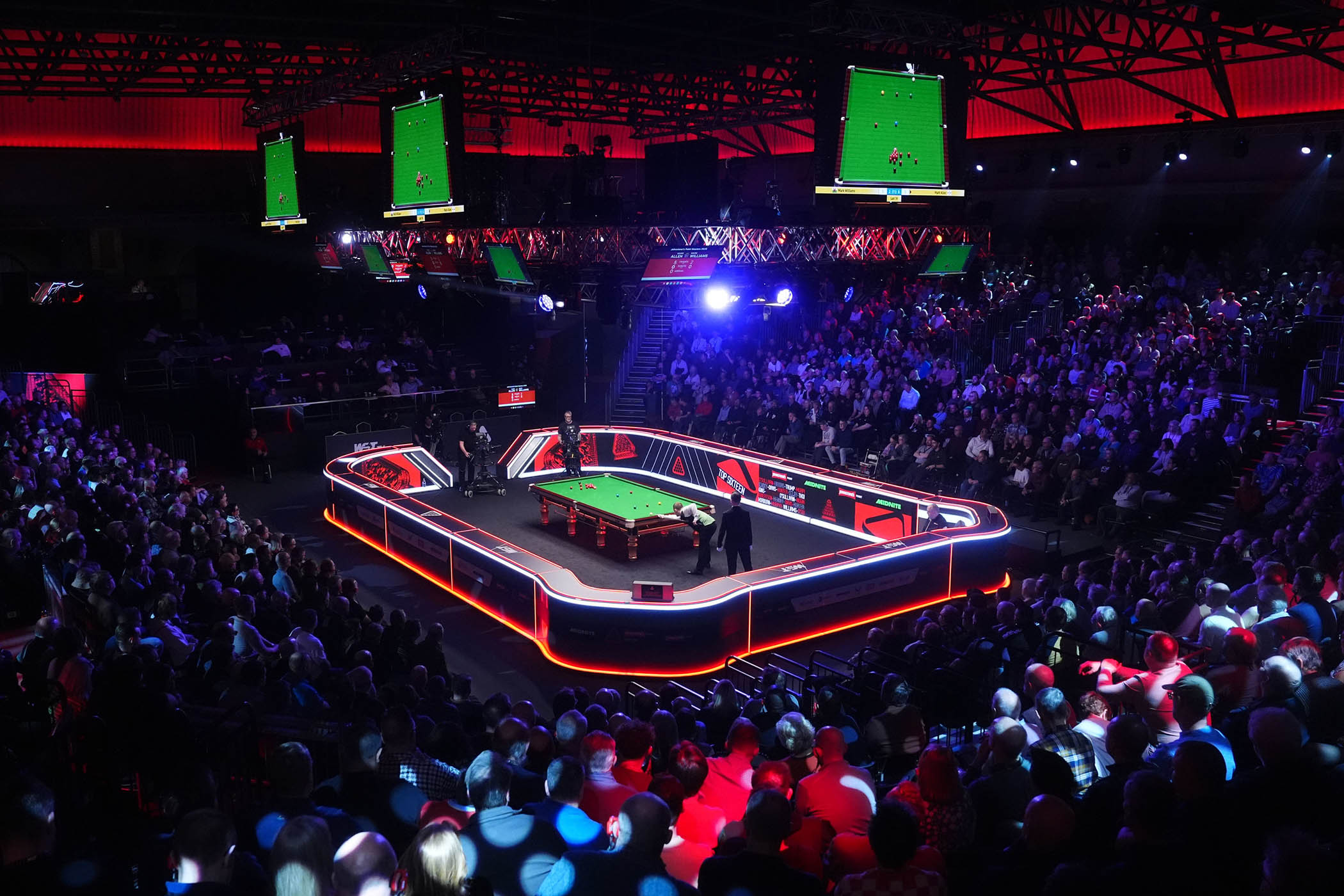

Photograph by MB Media/Getty Images