The plot of Saipan might not, on the surface, seem to offer rich material for a full-on movie. The setting is a work trip, nearly a quarter of a century ago. The plot centres on what is basically an argument that could have been an email. The stakes centre on when, exactly, Ireland will get knocked out of the World Cup. The denouement: one of the protagonists spends more time with his dog.

That character, admittedly, was the globally famous captain of one of the world’s biggest football teams, but still. The conflict between Mick McCarthy and Roy Keane at Ireland’s training camp ahead of the 2002 World Cup has a considerable half-life both in Ireland and within football, a piece of lore that continues to resonate. Outsiders to both, though, may not immediately grasp what drew Steve Coogan to take the part of McCarthy. Ireland is having a cultural moment, but this might be pushing it, just a touch. There must, as Coogan once said, be more to Ireland than this.

That reading is not correct. The stand-off at Saipan was far more than a squabble between two stubborn men. There is a reason it became a tabloid sensation that summer. It was about power, and control, and agency. It was a perfect distillation of what made Keane one of the most charismatic, compelling sporting figures of his generation. And, most importantly, it was one of those moments when the old collided headlong with the new.

For a Geriatric Millennial, there is something quite gratifying about the cultural revival of the late 1990s and early 2000s. This year’s hottest band is Oasis. Cool young people are wearing bucket hats and smoking cigarettes. The tyranny of slim-fit jeans is at an end. Tony Blair is once more the key to peace in the Middle East. The Premier League is all about set pieces. It turns out that we were right all along.

There is, of course, the possibility that this does not actually represent the triumph of the personal taste of my peers. Other explanations may be available. Perhaps it is an example of the journalist Hadley Freeman’s 30-year rule, the time it takes for one generation to grow up, assume control of the zeitgeist and decide that the stuff they liked as kids was the best.

Or maybe, as the writer Cord Jefferson has said: “Culture is no longer made. It is simply curated from existing culture, refined and regurgitated back at us.” As Kyle Chayka notes in his book Filterworld, the possibility of anything new is inherently and increasingly asphyxiated by our addiction to and reliance on algorithms. We have, he argues, outsourced taste to machines drawing on all that has gone before.

The mania for what we might call the Long 1990s is, in that light, part of an endless, winnowing cycle, the look and the feel and the ideas of a specific period of the past surfaced once more but stripped of the context that made them authentic. “There has never been a society in human history so obsessed with the cultural artefacts of its own immediate past,” as the music writer Simon Reynolds observed.

Football is no exception to this phenomenon. Its most obvious manifestation is in the canon of films to which Saipan will soon be added: it is different from the slew of documentaries on Sir Alex Ferguson and Luís Figo and David Beckham and the rest only in the sense that it is a dramatisation; its roots lie in the same period.

But the hold that the final gasps of the last century and the first breaths of this has on us is illustrated everywhere. McCarthy is now 66, which it turns out is the perfect age to launch a podcast, in which he chews over the news of the day with Tony Pulis. (McCarthy, it has to be said, is very good at it.)

Keane – now the face of an advertising campaign for the entire Sky network – may well be more famous as a character than he ever was as a player. The same is true of Jamie Carragher, Ian Wright and Gary Neville. Stick to Football has 1.5 million YouTube subscribers. The real stars of the Premier League are in the studio.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

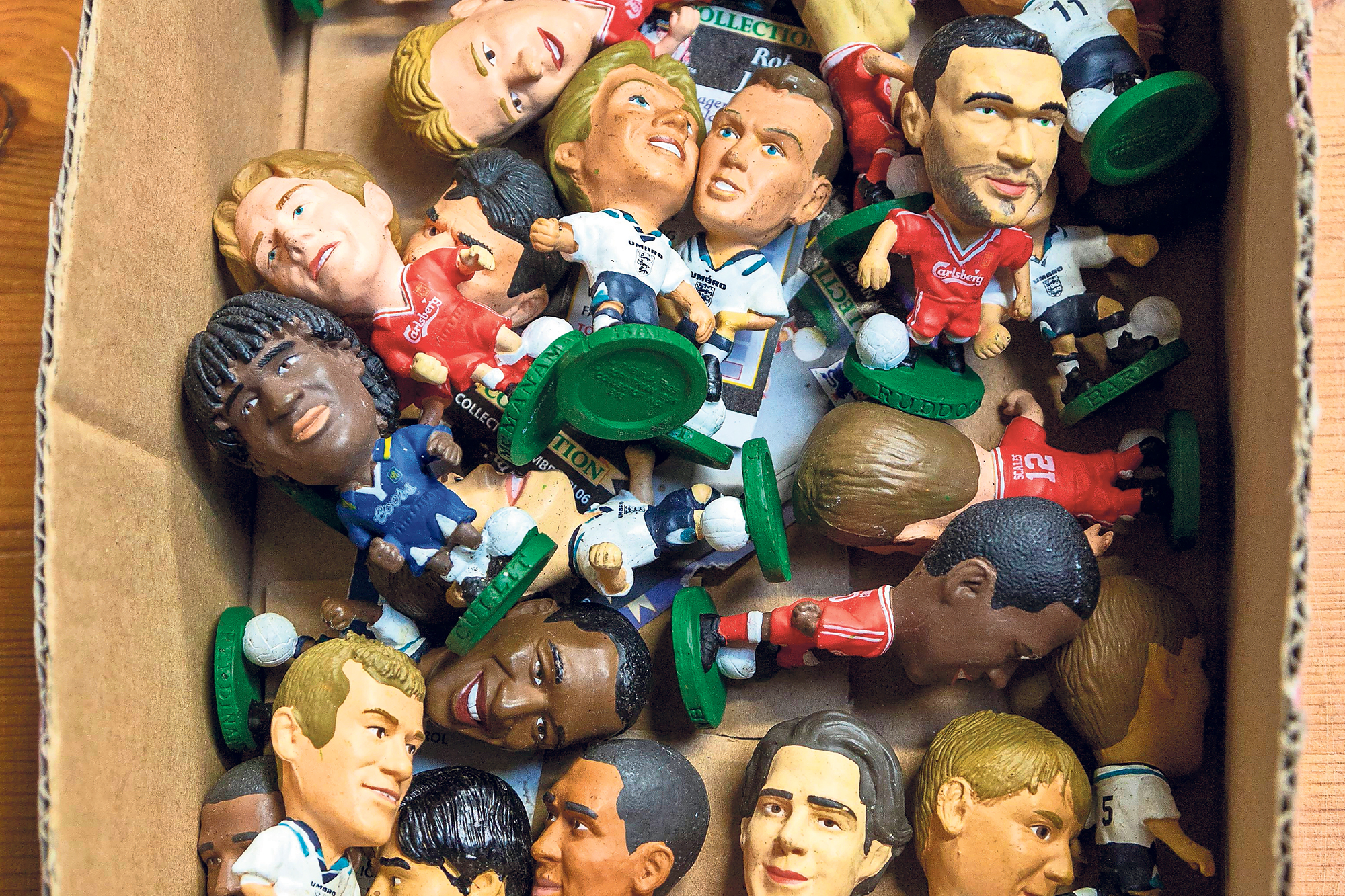

For a brief period last year, the “Barclaysman” trend flooded social media, Bjarne Goldbæk, Franco di Santo and Zoltán Gera suddenly catapulted back into the mass consciousness. The algorithms use the past as a nostalgia mine, excavating our childhoods and then serving our memories back at us, an easy and limitless dopamine hit.

It has seeped into the stands at Premier League games, too, where retro shirts now almost outnumber package-fresh editions. Their appeal is not hard to understand. They are, first and foremost, badges of honour, proof of service, a kind of mix of carbon rings and scratches marked into a prison wall. They are also design statements, their boldness and idiosyncrasies somehow more interesting than the smart, smooth realities of the current era.

And that, of course, is precisely what is so alluring about the period to which they belong, both in football and outside it. Our fascination with the late 1990s and early 2000s lies in the fact that they are recent and familiar but profoundly alien, deeply uncanny: a world that looks like ours, but without phones or WiFi, or the dim possibility that AI is about to take all of our jobs and the planet literally catch fire.

The football, too, is simpler, more innocent, more fun. There was no video assistant referee or fan YouTube channels or nation states and hedge fund billionaires shaping the game to their own ends, wrenching what was once a pastime from our control and turning it into a machine that produces rancour and panic for us and money and power for them. Saipan, and the period in which it happened, represent the last days of the old world. Now we look back on it, mourning what was lost.

Photograph by UCG/Getty Images