Six balls. That was how long it took for England to relinquish control of a game that was firmly in their grasp, and their best opportunity to win a Test match in Australia in nearly 15 years.

They led by 116 runs with eight second-innings wickets in hand, with Joe Root easing into his innings after being prised open by Mitchell Starc on a wild opening day. Australia, already rendered vulnerable by the absence of Pat Cummins and Josh Hazlewood, were sweating on the fitness of Nathan Lyon (hip) and Usman Khawaja (back), and were there for the taking. The thousands of England supporters in Perth felt the sun on their skin for the first time all day; the early-risers back home started to believe.

But six balls, three wickets, and no runs later, everything had changed. England’s engine room had vanished, their No 3-5 batters dismissed in a near-identical manner: looking to drive on the up through cover, and finding themselves exposed by the extra bounce that meant this Test was played in fast-forward. 76 for 2 became 76 for 5, and Australia were utterly dominant thereafter.

Barely five hours later, England peeled themselves off the field in a state of disbelief that they had not only surrendered such a strong position, but done so in such a hurry.

The first of the guilty trio was Ollie Pope who, in his 62nd Test – more than Jonathan Trott, Graeme Swann or Darren Gough – still exudes the air of a man learning on the job. Pope has evidently worked incredibly hard on his technique since the end of the English summer and played proactively for his 46 on the first day, repeatedly punching down the ground with crisp timing, but he made a crucial mistake on Saturday. England never once let Boland settle in the first innings, using their feet to throw him off his length and hit him out of the attack, but in the second, Pope played him with deference. It prompted Boland to suddenly grow taller, finding his groove and becoming the protagonist of the contest. Pope played-and-missed several times through the morning, and once more in the afternoon; Boland threw his next ball fuller, and his thick outside edge flew to Alex Carey.

Next came Harry Brook, England’s top-scorer in their first innings with a characteristically brash 52. There had never been much doubt as to how Brook would approach his first Ashes tour, but charging his second ball to launch Mitchell Starc through cover made for an eye-catching start. But this time around, he put his dancing shoes away and was stuck on the crease: he defended his first two balls, flashed at his third with hard hands, and threw his head back in frustration as Usman Khawaja held on at first slip. Brook has been a quick learner throughout his Test career, but this was an early lesson in the perils of driving on the up in Australia.

Steven Smith sensed the scale of the opportunity, and brought Starc – who had single-handedly kept England’s first innings in check – back for a second spell. The mood had changed markedly, and a crowd approaching 50,000 felt the magnitude of what was unfolding. This was the main event: the last man standing in Australia’s storied pace trio against England’s greatest-ever batter, with the game in the balance. Root has fielded months of questions about his record in Australia and repeatedly insisted that this tour was “not about me”, but this was a situation where England needed it to be exactly that.

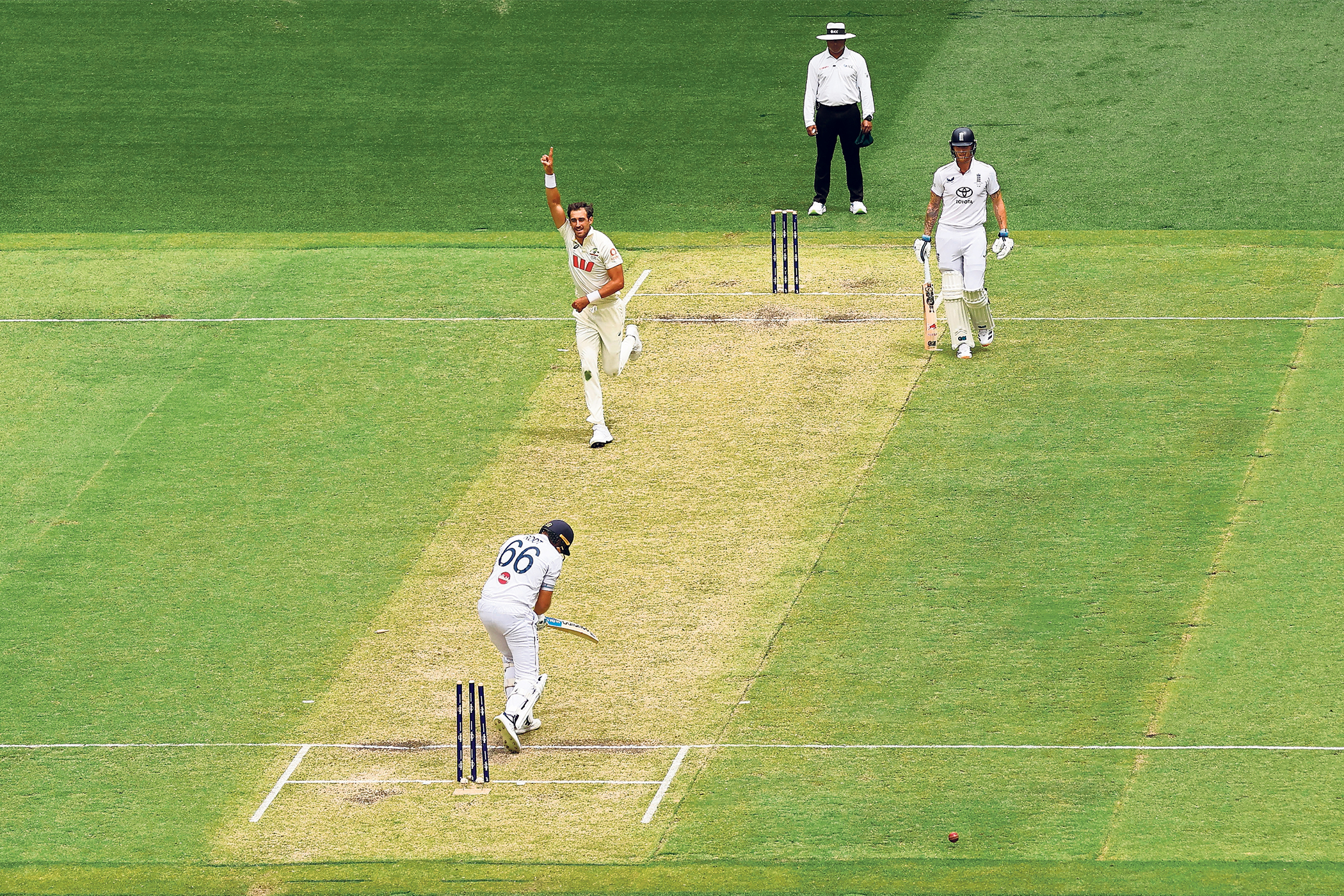

Instead, he lined up another expansive cover drive, only for Starc’s three-quarter-seam ball to deck in off the seam, take his inside edge and deflect onto his stumps. He doubled over his bat handle as Starc wheeled away, and the brief sense of relative calm had transformed into utter chaos. “Three identical strokes, pretty much the same length, same line, same result,” Michael Vaughan lamented on Fox’s commentary. Soon enough – and despite some unapologetic swiping from Gus Atkinson and Brydon Carse – Australia had run through the lower order, and Travis Head’s innings for the ages left England in the dirt. “I’m a little bit shell-shocked,” Ben Stokes reflected. “It’s a tough one, as we felt we were in control.”

England’s problem was not that they played attacking shots, as Head’s instant classic made abundantly clear. This was a pitch with steep bounce that offered significant seam movement throughout, and Smith’s painful effort in Australia’s first innings made clear that there was not much point trying only to survive on it. “It’s pretty obvious that the guys who managed to find success out there were the ones who really decided to take the game on,” Stokes said. “There was a lot happening out there.”

England peeled themselves off the field in a state of disbelief they had surrendered such a strong position

England peeled themselves off the field in a state of disbelief they had surrendered such a strong position

No, the issue was one of execution. Balls that pitched between six and eight metres from the stumps were dangerous throughout both days: Head’s success relied on the extent to which he threw England’s bowlers off their plans, ensuring he faced very few of those, and his homespun technique is perfectly suited for Australian pitches. But in the space of six balls, three of England’s best players all played with a straight bat, hard hands and minimal foot movement to balls in that danger zone.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Justin Langer, a Western Australian local, attributed it to poor planning: “If you do your preparation to come to Perth, you’ve got to take some time to get in… Driving on the up here? Very, very poor batting.”

For Root, it was a particularly painful way to go: after three previous Ashes tours without a hundred – or a win, for that matter – he has spent hours trying to work out a method for Australian conditions, but his dismissals in this Test could easily have been pulled from a highlights reel from his previous 14 in this country.

Brendon McCullum, England’s coach, described the Ashes as “the biggest stage, with the brightest lights” earlier this week. Those bright lights left his batters in a state of paralysis, as Boland and Starc turned the screw.

Photograph by AP Photo/Gary Day