José Mourinho has never really been the sort to allow time to heal a wound. By the time Tottenham Hotspur lifted the Europa League in May, a little more than four years had elapsed since his acrimonious departure from the club. He might have been expected to have mellowed, just a little, perhaps even to have allowed whatever resentment he once felt at his dismissal to have ripened into fondness.

But Mourinho has never yet encountered a bruise he is unwilling to punch. Mischief always trumps magnanimity. “Tottenham plays [in the] Champions League,” he said, when asked for a message of congratulation for his former employers. “And of course for Mr Levy, the millions that the Champions League gives, for him, is the best news.”

In many ways, it’s a classic Mourinho line: cutting, comprehensive, a knuckle-duster barely disguised by a velvet glove. It captures, in perfect clarity, exactly how football has seen Levy over the quarter of a century that he ran Tottenham. It casts him as an avatar for some combination of parsimony and avarice. It blurs the line between the institution and the individual. And, most of all, it indicates quite how large Levy has come to loom in our collective imagination.

It would not be quite accurate to describe Tottenham’s now former executive chair as the Premier League’s first celebrity executive. David Dein, his analogue on the other side of north London, was a prominent figure in the 1990s with Arsenal, some time before Levy took the reins at White Hart Lane. Manchester United fans had strong views on their club chair Martin Edwards throughout the 1980s; Anfield generally thought well of Liverpool chief executive Peter Robinson.

That Levy has had a comparable profile for the last two decades – that his face has become as familiar to many fans as those of the 13 permanent managers he hired and/or fired during his tenure – can be largely attributed to the character traits which Mourinho emphasised so deliberately. In the popular imagination, the 63-year-old was the hard-nosed, tight-fisted pinchpenny, the man whose approach to negotiating was so painful that Sir Alex Ferguson once compared it unfavourably with a hip replacement.

It was an image that gained traction in the four years that Levy worked with Harry Redknapp, a manager seen basically as his antithesis. They were projected almost as a comic duo: the wheeler dealer and the miser, the spendthrift and the skinflint. Even Redknapp acknowledged that they made for an “odd couple”, although he did not think that was especially unusual. “Anyone working with Daniel would be an odd couple,” he once said.

That he should have crossed paths with Redknapp at precisely the point when the game’s obsession not just with transfers but with the powerbrokers who conducted them was becoming all-consuming meant it was their relationship that came to define him in public perception.

That Levy oversaw a transformation at Tottenham is both widely understood and strangely overlooked. As Ian Graham, the pioneering analytics guru who would win fame for his work at Liverpool but who started in football as an external consultant for Spurs, points out in How To Win The Premier League, Tottenham were a “mid-table Premier League team, averaging 51 points per season” between 1992 and 2008. Levy’s “financial acumen and running of the club”, he writes, helped them shed that image.

Related articles:

In the 17 seasons since, Spurs have missed out on European competition just twice. They are, and they see themselves as, a Champions League club. They have made the finals of both of Europe’s major club competitions. They have one of the most sophisticated and well-regarded training facilities in world football; they have a stadium seen as the best in the Premier League.

And they have done it all while retaining tight control of their finances; Deloitte, in its most recent report into the economics of the Premier League, found that Spurs spend just 42% of their income on wages. Levy is not popular with his peers; plenty complain that trying to do business with Spurs is too exhausting to be worthwhile. Other Premier League executives, though, have always been staggered by the amount of vitriol heaped upon him. Spurs, after all, may well be the best-run club in England.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

That there were protests against Levy’s role even as Spurs made their way to the Europa League final against Manchester United last season suggests that none of that concerns fans quite so much as his apparent unwillingness to loosen the purse-strings.

His determination to “drive a hard bargain at the best of times”, as Redknapp wrote in his autobiography, Always Managing, has not been seen as a positive, proof of cool, rational stewardship. Football is an industry that values the cavalier more than the cautious. Levy’s prudence has been cast instead as a lack of ambition, even greed.

There is some truth to that. As Antonio Conte once said, amid the ruins of his own time at Tottenham: “Twenty years there is the owner, and they never won something. But why?”

Levy’s approach has come at a cost: they have missed out on players because some see Tottenham as a dead end, not a through road; Levy’s insistence on waiting until the last minute to strike a deal has always made more business sense than sporting; failing to bolster Mauricio Pochettino’s resources after they lost the Champions League final to Liverpool in 2019 counts as a colossal missed opportunity.

Judging by the statement published on behalf of the Lewis family in response to his departure on Thursday night, the club have adopted that version of history. “They want what the fans want: more wins, more often,” as a source close to Tottenham’s controlling owners said. Nobody thought to mention that such a sentiment is only possible because of all that Levy, popular or not, has done.

Levy’s time at Spurs

2001

Appointed as club chair

A lifelong fan, he takes charge aged just 39, warning there must be a balance between shareholders “who want profit” and fans “who want success”. “Sometimes,” he said, “the two do not go together.”

2008

Tottenham win League Cup

The first trophy, won by Juande Ramos, the fourth permanent manager that Levy had appointed.

2010

Spurs make Champions League

Under Harry Redknapp, Spurs finish fourth and qualify for Europe’s elite for the first time.

2015-16

New stadium, title miss

Construction on the new stadium begins in the summer of 2015. The following season, Spurs push for the title until a late collapse sees Leicester win it.

2019

Champions League final

The first game in their new £1bn stadium takes place in April. Two months later, they lose the Champions League final 2-0 to Liverpool.

2021

Another trophy chance wasted

José Mourinho is sacked a week before the League Cup final. Spurs lose and go on to finish seventh in the league.

2024-25

Europa League glory

Spurs sink to 17th in the league under Ange Postecoglou but their season is saved by beating Manchester United in Europe.

2025

Levy out after almost 25 years

Levy is said to be “heartbroken” at being eased out as the owners insist they want “more wins, more often”.

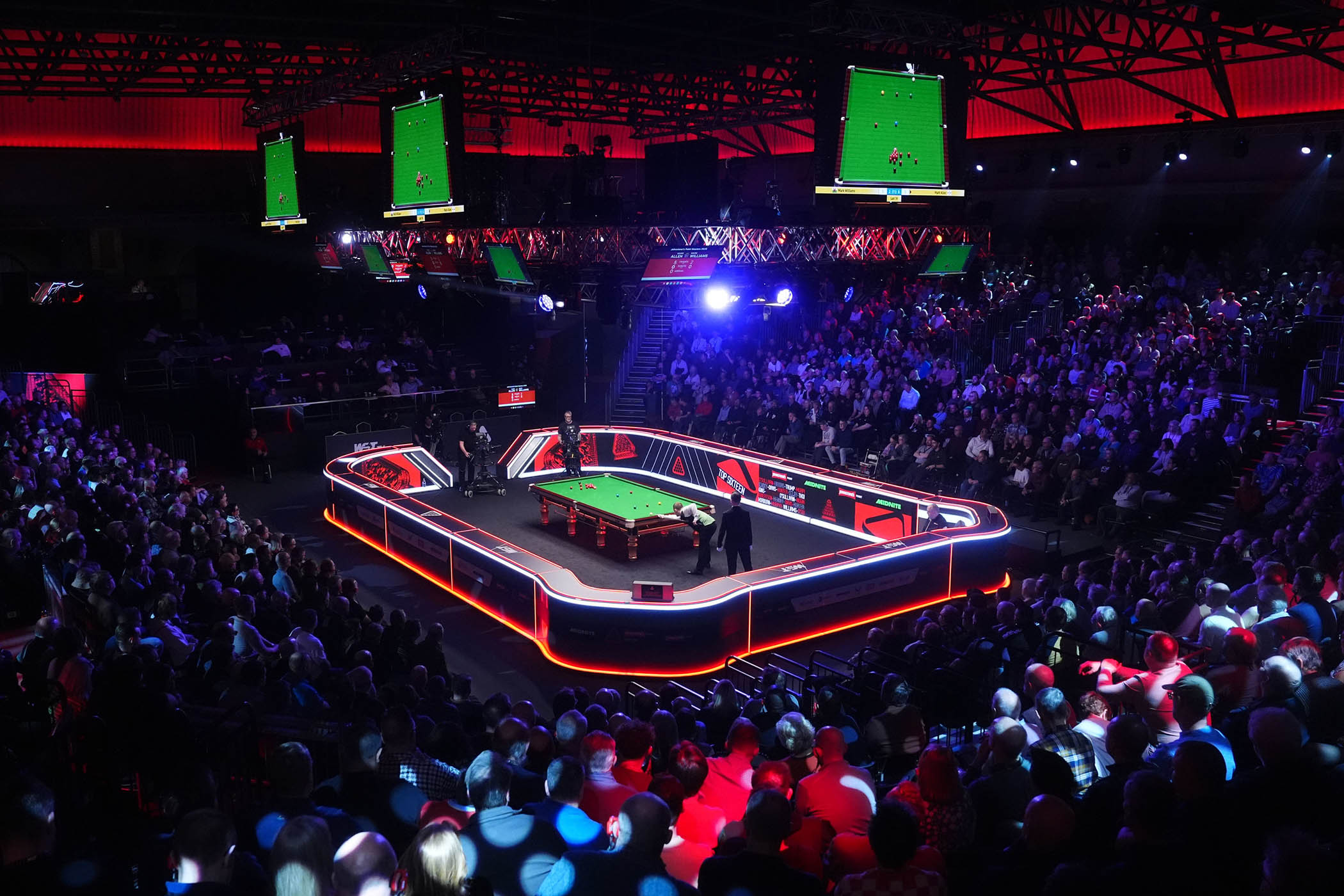

Photograph by Hollie Adams/Getty Images