Welcome to the Sensemaker, our daily newsletter. It features calm and clear analysis on the stories driving the news across tech, politics, finance, culture and more. The Sensemaker will appear here every morning, but to receive it in your email inbox, sign up on our newsletters page.

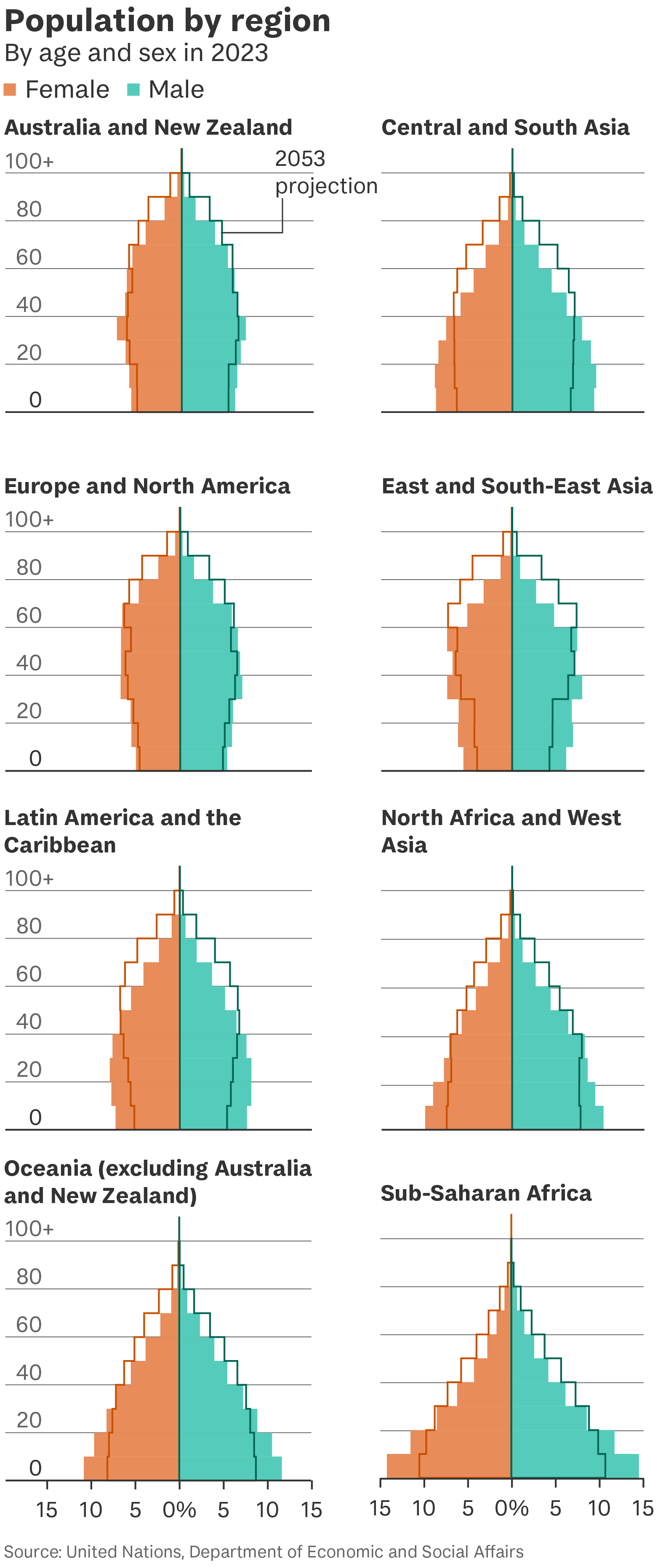

The world is experiencing an “unprecedented” fertility crisis, the United Nations said in a landmark report released this week.

So what? The worry used to be quite the opposite. In 1968 a Stanford biologist called Paul Ehrlich warned of a “population bomb”. His dystopian scenario, conceived during the baby boom, imagined an explosion in numbers that would cause famines and social upheaval as people scrambled for dwindling resources.

But it never went off. Today demographers predict the opposite: a population collapse. Birthrates have been falling for decades, especially in the rich world, and warnings about the consequences are becoming ever more stark. Most countries are now below the “replacement rate” of 2.1 children per woman, where there are more deaths than births.

Mind the drop. Last week Japan announced that its birthrate had fallen to 1.15, the lowest since records began in 1899. The picture is similar throughout the world. From 1960 to 2023 birthrates declined from:

•

6.77 to 1.83 in Mexico;

•

2.91 to 1.55 in Norway;

•

2.72 to 1.53 in the UK; and

•

6 to 0.81 in South Korea.

Cause célèbre. The issue of falling birthrates is a mantle that has been taken up by far-right leaders. Hungary’s Viktor Orbán promotes “traditional family values”. Elon Musk says “civilisation will disappear” unless the trend is reversed. Trump has called himself the “fertilisation president”. But beyond their rhetoric (and solutions) is a genuine problem.

Behind the numbers. Electing to have a smaller family is a liberatory choice. Women with access to contraception have far more personal freedom and can forge careers. But the UN says that millions are unable to have the children they desire. Its poll across 14 countries found most people want to have bigger families but can’t afford them. The reasons it cites include

•

the soaring cost of housing;

•

prohibitive childcare costs;

•

insecure jobs;

•

poor parental leave; and

•

people starting families later in life.

Why it matters. Being unable to bear the cost of having children is not just disempowering. It is economically costly. When deaths outstrip births, there are fewer taxpaying workers to support the growing numbers of pensioners. Several countries have introduced policies to get women to have babies.

•

South Korea has spent more than $200 billion on monthly stipends for families, better paternity leave and state-supported childcare.

•

China removed its one-child cap in 2015, and then a two-child cap in 2021. Local officials cold-call married women asking if they are going to have children and universities run “love courses” for single students.

•

France gives generous tax breaks, cash handouts and retirement benefits to parents.

Damage limitation. Some policies have succeeded in slowing the decline. There would have been up to 10 million fewer births in France without its family-friendly policies. But the overall trend line hasn’t shifted. The number of marriages in China, a tightly controlled society where unwed couples and single people rarely have children, has fallen by more than half since 2013.

Outlier. Sub-Saharan Africa is the only place to buck the trend. Its birthrate is 4.3, compared with the global average of 2.2, with a population set to double by 2070. Within 25 years half of all births will be on the continent.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

For now rich countries have topped up dwindling labour pools by welcoming migrants. In the future that might not be an option. A Lancet article found 75 per cent of countries would fall below the replacement rate by 2050. By 2100, it would hit 97 per cent. Just six countries would be above replacement including Niger, Tajikistan and Somalia. This may relieve some pressures, such as childcare costs and environmental degradation, while creating many others.

Low fertility future. Another study from 2023 concluded that if the global birthrate fell to 1.66, about the same as in the US today, the global population would collapse from about eight billion to less than two billion within 300 years.

What’s more... That’s about the same as a century ago. Humanity’s population surge over the past 100 years has gone hand in hand with advancements that allow for longer and healthier lives. This may prove to be a blink in history.

Graphic by Bex Sander