In 1987, the American cartoonist Gary Larson drew one of his surreal Far Side sketches of two apes sitting on a branch. The female, wearing 1960s-style glasses, picks something out of the male’s fur and asks in the style of a sitcom housewife: “Well, well, another blonde hair… Conducting a little more ‘research’ with that Jane Goodall tramp?”

The executive director of the Jane Goodall Institute, founded by the British primatologist, was furious. Lawyers were consulted and angry letters written to the papers that ran it. Meanwhile, Goodall herself was in Tanzania studying chimpanzees, as she had done for 27 years, blissfully unaware. When she visited America and was told of the insult, she let out a ripe guffaw. “Wow! Fantastic!” she said. “Real fame at last!”

Far from being offended, she offered to write an introduction to Larson’s next anthology, and he gave her institute permission to put the cartoon on a T-shirt and sell it to raise funds. He later visited Goodall’s research centre in Gombe national park, Tanzania, where he was attacked by a chimp named Frodo, who perhaps felt he had to defend her honour.

Larson had in fact paid Goodall a compliment, recognising the essence of her life’s work with the apes of east Africa: that they were much closer to us than had previously been acknowledged. “Are they human-like or are we animal-like?” she asked.

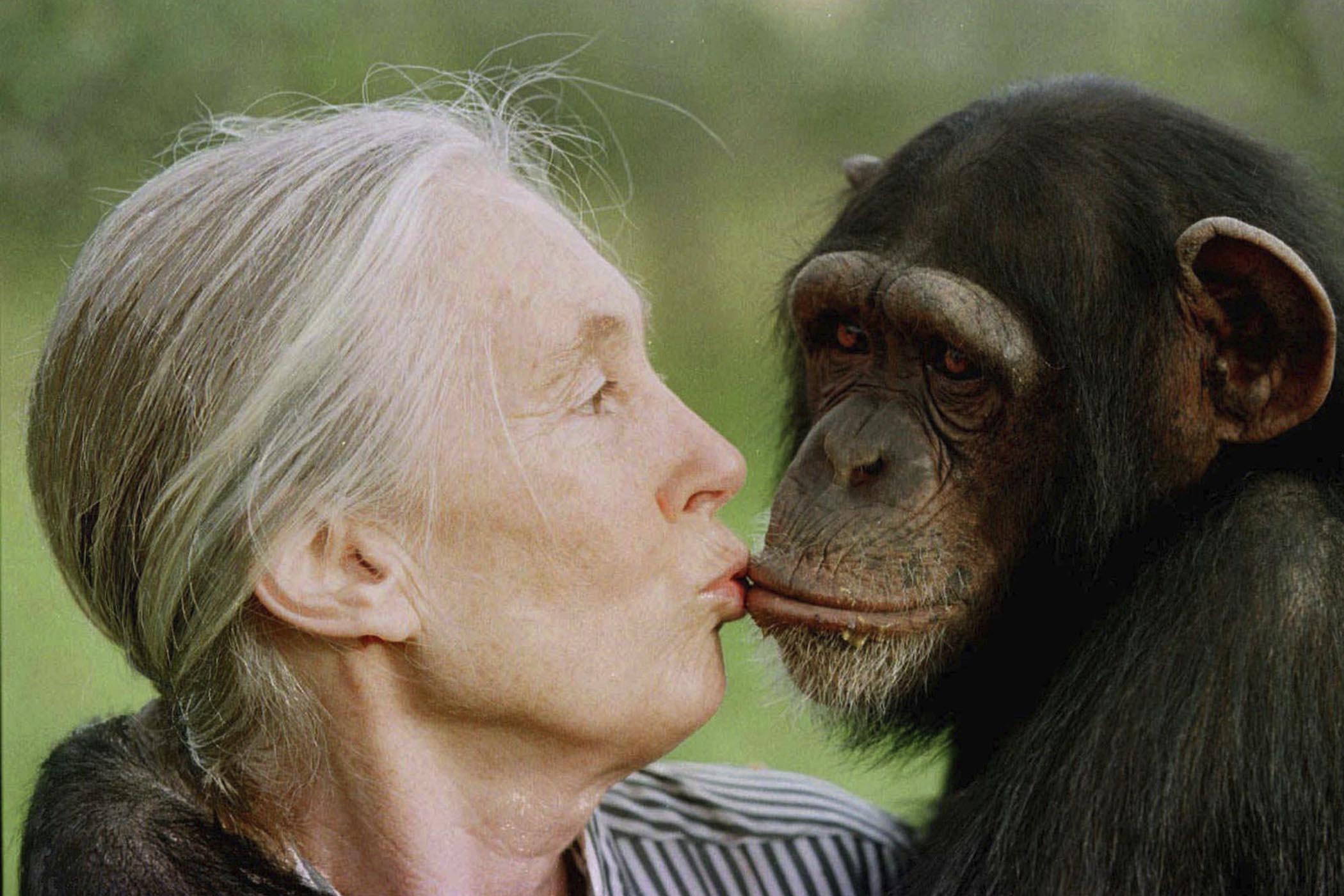

The vast majority of the structure of our DNA is identical, but she found that the species also have emotional similarities. “They can reason, they can solve simple problems,” she said in 2001. “They can feel happy, sad, fearful, they can feel despair, they have a sense of humour and they can show, on the one hand, brutality like us and, on the other, compassion, caring and altruism ... They can recognise themselves in mirrors.”

Some felt she took her anthropomorphising too far by giving her specimens names rather than numbers. They included the elder statesman David Greybeard, her favourite; the bold Goliath; Aunt Gigi, a sterile female who looked after the young; and the belligerent Mr McGregor. Over 60 years in their community, Goodall observed four generations.

One revolutionary discovery came when she watched David Greybeard sticking stalks of grass into termite holes and removing them covered with insects. This “fishing” showed the chimps’ ability to use tools. She also found they would eat red meat rather than a vegetarian diet and, to her sadness, wage wars. In 1974, her apes divided into rival tribes and fought for four years until all the males in one group were killed.

Valerie Jane Morris Goodall was born in Hampstead in 1934. Her father was a businessman and racing car driver who divorced her novelist mother when Jane was a teenager. Thereafter she was raised in an all-female house with her mother, sister, grandmother and two aunts. Her mother impressed on her that she could do anything with effort. What she most wanted was to work with animals in Africa. Her father had given her a toy chimpanzee called Jubilee and she loved to read Dr Dolittle and Tarzan.

Related articles:

In her early 20s, she was invited to stay on a friend’s father’s farm in Kenya and saved money from waitressing to buy a one-way ticket. Once there, she wrote to the palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey to seek career advice. Leakey was looking for a chimpanzee researcher and sent the 26-year-old Goodall into the forest of Gombe. He insisted she be accompanied for her safety – surprisingly, she took her mother. She was one of three women Leakey mentored, believing they had greater patience than men. With Dian Fossey, who studied gorillas, and Biruté Galdikas, who observed orangutans, he called them his “Trimates”.

Goodall had little formal education, but with Leakey’s support went to Cambridge in 1962 to begin a PhD in chimpanzee behaviour. In 1965, she came to public attention via a National Geographic documentary called Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees. She was the subject of more than 40 films and wrote 16 books for adults and several for children.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

She was married twice, from 1964-74 to Baron Hugo van Lawick, a Dutch aristocrat and wildlife photographer with whom she had a son. In 1975, she married Derek Bryceson, director of Tanzania’s national parks, who died in 1980.

In 1977, she founded her eponymous institute. Its headquarters are in Washington DC and it has 27 offices around the world. Barack Obama was one of many leaders to pay tribute. “Jane Goodall had a remarkable ability to inspire us to connect with the natural wonders of our world,” the former US president wrote on X. “Her groundbreaking work on primates and conservation opened doors for generations of women in science.”

Goodall was an enthusiastic advocate for wildlife and environmental conservation to the end of her life, travelling the world to give speeches, in which she would demonstrate her mimicry of chimp calls and raise funds for ape refuges. She died last Wednesday in Los Angeles during a speaking tour of the United States. At the Forbes Sustainability Leaders Summit in New York a week earlier, she had warned about the damage man is doing to Earth.

“We are the most intellectual species to walk the planet, but we’re not intelligent,” she said. “If you’re intelligent you don’t destroy your only home.”

Dame Jane Goodall, primatologist, was born on 3 April 1934, and died on 1 October 2025, aged 91

Photograph by Jean-Marc Bouju/AP