The Francis Crick Institute is a cathedral of biomedicine in the heart of London, a centre for 2,000 scientists to push the limits of research and a monument to one of the men who made it possible. In 2017, the year after it opened, James Watson was asked if he were similarly immortalised anywhere. “I don’t need a building named after me,” he replied. “I have the double helix.”

Crick and Watson are intertwined in the public mind like the structure of DNA that they discovered at Cambridge in 1953. Crick’s description of it as “the secret of life” was no exaggeration.

Until that point, scientists knew DNA carried genetic information, but not how. The two men used an X-ray image, obtained from Rosalind Franklin without her permission, to show that deoxyribonucleic acid was structured as two chains of genetic information that twist around each other like a spiral staircase. The chains are the instructions for new cells to form.

That fact underpins many other discoveries. We know that humans interbred with Neanderthals, and can prove who our parents were, or if someone was involved in a crime. Diseases from Huntington’s to breast cancer have been mapped. CRISPR, a tool for editing DNA, has offered treatments that were once unimaginable. DNA research promises the possibility of personalised cancer therapies, or that someone may create mirror bacteria, with DNA helixes in the opposite direction, that could wipe out life on Earth.

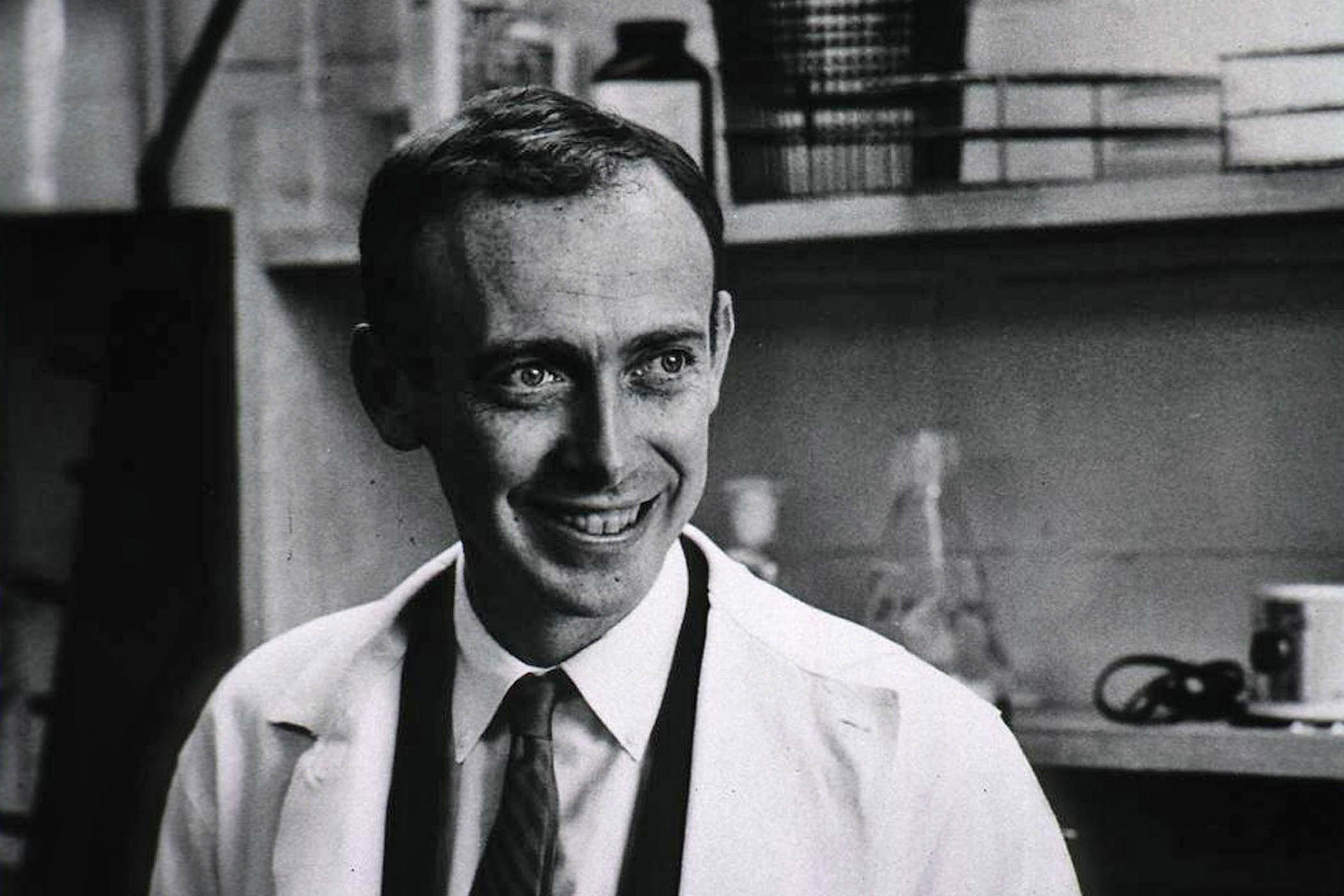

James Watson, who died last week aged 97, may be linked for ever with Crick, yet their partnership lasted only two years. Watson was born in Chicago in 1928 and arrived in England aged 23 to join the Cavendish laboratory, which was leading the way in DNA research in the 1950s.

Watson found in his English counterpart a willing collaborator, but the men were opposites. Crick was 12 years older and enjoyed parties, pranks and, later, LSD; Watson was awkward, single-minded and often insensitive to the feelings of others. After their discovery, Watson returned to the US, although the pair remained fond of each other. They won the Nobel prize in 1962, alongside their colleague Maurice Wilkins.

At Harvard, Watson focused relentlessly on understanding DNA, believing it to be more important than evolution or taxonomy, fields he described with characteristic bluntness as “stamp collecting”, since they were merely attempting to describe the world. His colleague EO Wilson, an evolutionary biologist, said Watson’s desire to wipe away other fields made him the “Caligula of biology” and described him in 1994 as “the most unpleasant human being I had ever met”, although they later reconciled.

‘I don’t need a building named after me. I have the double helix’

‘I don’t need a building named after me. I have the double helix’

In 1968, Watson took over the Cold Spring Harbor laboratory in New York state, an institution he led for 40 years. The same year, he married Elizabeth Lewis, a research assistant 21 years his junior, and they had two sons, Rufus and Duncan. Rufus developed schizophrenia, which motivated Watson to map the human genome.

He was appointed head of the Human Genome Project when it was established by the US National Institutes of Health in 1990, but resigned after two years when he fell out with the NIH’s director, Bernadine Healy. She had wanted to patent the gene sequences emerging from the project, something that would have potentially stymied future research. Watson’s reputation for outspokenness finally derailed him in 2007.

He gave an interview saying that Africans were, as a group, not as intelligent as white people. “All our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours – whereas all the testing says not really,” he was quoted as saying In the furore that followed, Watson apologised, saying there was “no scientific basis” for the statement – overall IQ test results have been rising for decades, indicating that intelligence testing includes a social or environmental dimension – but he stepped down from Cold Spring Harbor a week later.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The scandal dogged him for the rest of his life and he disappeared from the public realm, except to offer his Nobel medal up for auction in 2014. That he was the only laureate to ever do so was taken as an implicit rebuke to the scientific community for turning its back on him. The medal was bought by Alisher Usmanov, a Russian oligarch, for $4.1m at Christie’s, and then returned to Watson.

There was to be no rehabilitation. In 2019, he was asked if his views on race had changed. “No, not at all,” he said. He died last week after a short illness and is survived by his wife, his sons and the legacy of his double helix.

James Watson, molecular biologist, was born on 6 April 1928 and died on 6 November 2025

Photograph by Avalon