Photographs by Benjamin McMahon

Bella Freud, known first for her tailoring and more recently for her podcast, has a voice like corduroy and a silken life that, at times, has appeared unravelled. We meet on a cold morning in November at her great-grandfather’s house in north London – a museum now and a place of pilgrimage for many, including hushed groups of tourists who today pose for photos on a replica of Sigmund’s psychoanalytic couch. It is somewhere Bella rarely visits, partly due to the sense that she mustn’t get “seduced” by a dynastic family she was not brought up with, and the enduring feeling instead that “I’ve got to prove myself.” She whispers, embarrassed, as we walk up the carpeted stairs, past cuttings from Sigmund’s begonia, and into a private office lined with books.

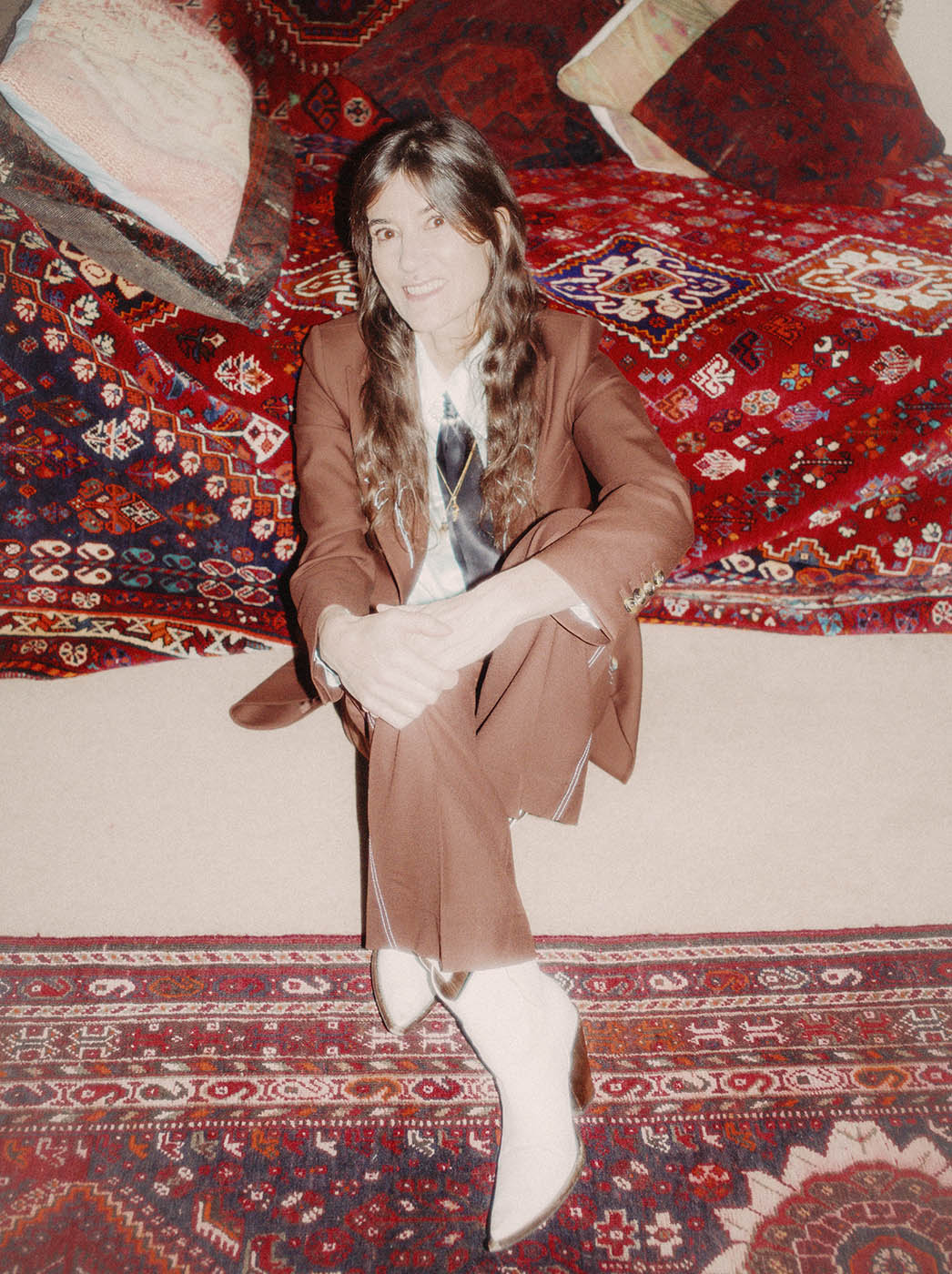

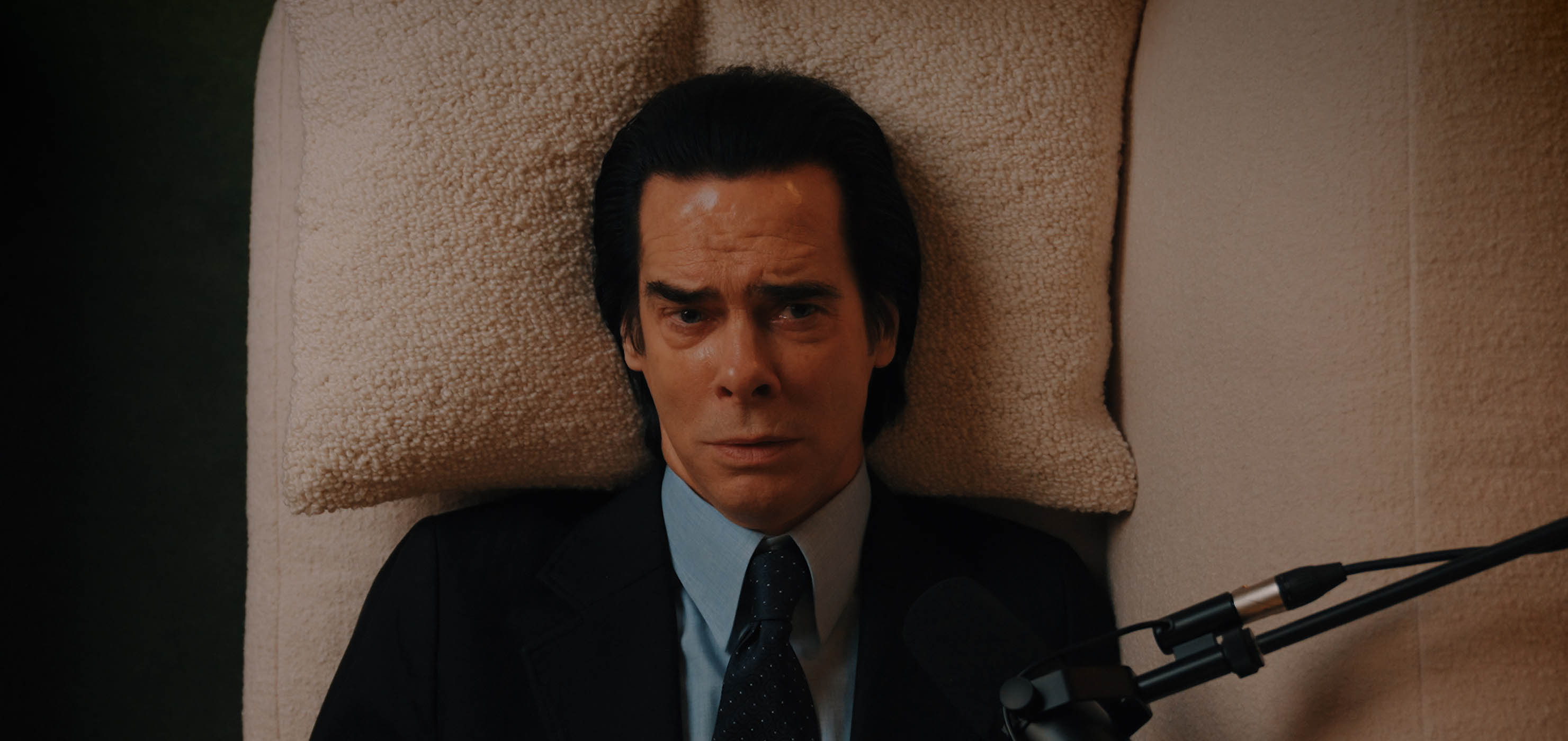

Freud is wearing a slim, chocolate-brown suit, a herringbone tweed coat draped over her lap and pearls close to her neck to reflect light on to her face. Sometimes, she says, she has anxiety dreams in which she’s supposed to be filming an interview for her podcast, Fashion Neurosis – during which she sits in her late father Lucian’s leather chair behind guests who lie gazing upwards on a white bouclé sofa, talking about themselves through the prism of clothes – but doesn’t know who she’s interviewing. In reality, her interviews are meticulously researched and surprisingly intimate. Freud has been a designer for much of her life. With the podcast, she wanted to make something that showed how remarkable fashion people can be: people who are “just trying to make fantasies come real,” she says. “And it’s not really about fashion. It’s about overcoming adversity.” The designer Rick Owens discussed how early body dysmorphia led to his distorted designs. The model Kate Moss revealed a game she plays, “fashion police”, in which she judges tourists from her car. The couch has been visited by so many famous people – Nick Cave and Cate Blanchett and Courtney Love and David Cronenberg and Eric Cantona and Helena Bonham Carter – all of whom have opened up as if to a therapist.

Freud’s clothes are worn typically by female directors or glamorous authors, and last year by the Princess of Wales, too. When she started designing, in 1989, she was working for Vivienne Westwood, “who was one of the great designers of our time. And I was conscious that I didn’t do what she did.” Rather than designing “fashion”, she says, “I was after a look.” When she started making jumpers, she’d draw a picture or write a word, then blow it up on the photocopier and pin it on to see how it felt: the jumpers said things like “Ginsberg is God”, or “Hello cunty”. Growing up, words and language were “an armour”, and she was inspired by slogans she saw on protest signs. “But they’re not a directive. You’re not telling people what to do.” The first time I met her, over 20 years ago, I was interning at the Face magazine and had spent the day schlepping around London collecting clothes for a shoot. When I arrived to pick up a Bella Freud piece at a tiny boutique near Carnaby Street, Freud was there herself. And instead of treating me as a nuisance courier she was terribly kind, and human.

I don’t believe in self-deprivation. I really don’t want that in my life. I want pleasure

I don’t believe in self-deprivation. I really don’t want that in my life. I want pleasure

Her accomplishments have not been linear. But now, 35 years into a career and in her 60s – “Do we have to put my age? I don’t like categorising things that feel like traps; I just want things to feel fluid, with a feeling of freedom” – she is experiencing a new kind of success. Her 2024 collection for Marks & Spencer, which included affordable versions of her suits, sold out in eight hours. Her 2025 collection extended to homeware and slogan knits for babies and dogs, and very good pyjamas. I wondered if the punk in her felt any anxiety about making clothes for M&S? “More the kind of snobby fashion part of me,” she says. “But it was really good. I got a lot from it, and to make money in fashion is really stimulating, and so hard. And those things give you confidence, and when you feel confident you have a better eye and your decision-making process is swifter, and those things then inspire confidence in other people that you know what you’re doing.” By the time her second collection landed, the combination of hit jumpers and popularity of the podcast had helped cement Bella Freud, once only a cult name, firmly in the mainstream.

The decision to interview guests on a couch and play with Sigmund’s psychoanalytic iconography didn’t come easily. Her father Lucian, one of the most important painters of the 20th century, “never talked about his family. So I’ve always been, like, ‘You are only as meritable as the last thing you made.’ But then I thought, ‘Oh, come on, get over it.’ And then it was perfect.” She found that asking podcast guests to use the Freudian-style couch came with “strange” benefits; she discovered, for instance, that “people are different when they’re lying down. And then I’m different, more attentive.” After recording a few episodes she realised she “seemed to be good at this”, and she wondered, quietly, if it was in her blood. She leans forward now for emphasis, talking through her veil of dark hair. “I’m obviously making a joke and taking advantage of ‘my history’, because there could be nothing worse than doing a mawkish kind of tribute…” But being at the Freud Museum was stirring a kind of unusual comfort. “It’s really nice, hearing those voices. I suppose the older I get, the more moving it becomes.”

Freud grew up with a sister, Esther, whose book Hideous Kinky novelised their itinerant childhood, and included the time when their mother, Bernardine Coverley, left six-year-old Bella in Morocco, unable to find her on their return. Bella never had a “big sense of family”, she says. Lucian was always clear that his art came before his (estimated) 14 children. But recently family has begun to loom larger in her thoughts. “And now I feel like I can enjoy that a bit more. Like, I remember my son brought back this graphic novel about Sigmund Freud, so I read it and thought, actually, this is great.” As well as being a route back to some acceptance of family, the book – unavailable in the gift shop downstairs, madly; we checked – remained “so vivid in my thoughts”, like “finding something kind of incomprehensible or inaccessible, and then, suddenly, finding a way to see”.

Bella has been in therapy on and off throughout her life, occasionally revisiting memories from her childhood. She recently drove past the luxurious home of somebody she knew who’d been born into poverty, “and thought, ‘you never forget what you grew up with’”. Though her current house is impossibly chic (a retro-modernist apartment behind a west London warehouse), when she goes home she always half expects to return to the cold chaos of her youth: the baths in sinks, the lack of food, her single pair of socks. “I thought, ‘God, isn’t it weird the way this never evaporates. It’s more like the now stuff evaporates.’ Like, when I ask people on the podcast, ‘What was the first thing you became obsessed with that you wore?’ they can always remember.” For Bella it was a pink gingham shirt that belonged to a girl she met at a summer camp – the shirt represented the glamour of normality. When she asked the same question of Julianne Moore, the actor talked about a brown dress she wore for an appointment with a beloved dentist. Kate Moss told her about a pair of pale-pink shoes she loved so much she wanted to sleep in them. And Nick Cave recalled a pair of herringbone flares.

“These things from childhood don’t fade away at all,” Freud says. “It feels very present. It’s my training, really, everything I went through, but it’s not dominating now in the brittle way it used to.” One therapist told her about the concept of a “threat response”, where the body of someone on heightened alert shifts into a “fight or flight” mode at any sign of perceived danger, “and it resonated. I thought, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s what I lived off for ages.’ And now I don’t.” Under the cloud of the pandemic, she decided her goal was “to be softer”. Lose a layer of defensiveness. “I remember my therapist saying to me: ‘Maybe you can get over yourself.’”

Nick Cave on the couch, 15 January 2025: ‘In my view, it’s an absolute disaster to try and find a decent pair of men’s shoes. Women’s shoes are an entirely different thing, and they’re the most gorgeous shoes in the world.’

An image then, of Bella Freud clambering over the many selves she has created and lived, from the child in chaos, to a teenager drinking with her father and Francis Bacon, or working at Vivienne Westwood’s punk shop Seditionaries, through to the bohemian domesticity of marriage to the writer James Fox in 2001, and motherhood, and amicable divorce, and a loose, merry fame. In her half-sister Rose Boyt’s recent memoir we meet Bella as she moves in with Boyt at 16. Boyt describes her as “her own person, a child coming into my home with too much sexual allure, too much ruthless desire for excitement and danger. She left sixth-form college almost before it had begun, had to be fed because she didn’t want to waste her money on food, and realised her ambition to get stuck into everything cool and dangerous as soon as possible, with hardly a care for herself or for me.” This appears to be how she lived for some time, a restless energy that took her at 21 to live in Italy with a Roman prince 36 years older. She studied tailoring there, and completed her sartorial education by wearing her boyfriend’s too-small 1970s suits, before returning to London to become Westwood’s assistant.

In Freud’s first memory she is a tiny baby being bathed by her mother. “I remember her holding my head up. And this panic, realising I couldn’t control what was happening, and giving up. And then it was fine. It’s amazing what will happen when you stop trying to control everything.” She gazes towards the bookshelves, her chin raised. “It wasn’t a very cosy home. But my mother did hold the back of my head.” In the life that followed, control was something she alternately fought and embraced, sometimes using food, other times fashion. Today, “I don’t believe in self-deprivation. I used to when I was much younger. I thought it was training. But I see it doesn’t work, and I really don’t want that in my life. I want pleasure.”

Julianne Moore on the couch, 12 March 2025: ‘I’m an anxious packer. I think about packing, you know, as it becomes imminent, as it’s on my horizon, and I start to really, really worry as if it were a task I won’t be able to complete.’

As well as being a noted designer, Freud (like her sister Esther and her half-sisters Rose and Susie Boyt) is a beautiful writer. Every week she shares stories on Instagram, in which she transports readers fondly, briefly, into grim or smoky rooms of the 1970s, picking at the thread of a memory. One might be about a teenage friend she revered (and who was having an affair with Lucian), or starry experiences with artists, or living on the edge of a forest with her mother’s new family (“I loved the nature, but I couldn’t bear this emptiness which was all inside me”), or sitting for a portrait for her father. There was one about another friend, an addict, whose psychiatrist knew she’d started using again because she’d changed her hairstyle. Bella asked what she’d done to her hair, she wrote, and “I remember almost her exact words. ‘I had slicked it back with hair gel to go with my new ivory silk Nehru jacket and my jeans tucked into burgundy leather boots – soul girl style.’” The memory led to Freud considering her own hair journey. When she left home at 16 a friend cut her waist-length hair into a punkish crop, and she felt as though she was shedding her unhappy childhood. Soon after, having been frequently mistaken for a boy, she approached Vivienne Westwood at a gig and asked for a Saturday job. “She eyed up my new look, and said yes. It was the beginning of the rest of my life.” When she has time to write the memoir, it will be a bestseller.

More of these memories litter our conversation, each one a lesson in love, work or empathy. Once she was walking through a market in Soho with the model and Westwood muse Sara Stockbridge, all dressed up, and a market trader started laughing uproariously with pleasure, or shock. “And if you can get over yourself in that moment…” she starts. “It was really useful to know people are also threatened by extreme beauty.”

Graydon Carter on the couch 21 May 2025: ‘‘Unlike a lot of people who wanted to extend their adolescence into their 40s… I wanted to dress like an adult as soon as I got to my 20s.’

Later, Freud joined Westwood (not yet thought of as a national treasure) when she was interviewed on Wogan, watching from backstage as Westwood was ridiculed for her attitude and style. “She taught me that you don’t have to have approval. People aren’t going to necessarily like what you do, or even like you, and you need to be ready to cope with that. I mean, it always hurts and it makes you question yourself, but you need to go through that again and again.”

It was a similar lesson she learned from sitting for her father: of discipline, perseverance, tenacity. Lucian would gossip while he painted, annihilating friends, or telling her about meeting Picasso, or reciting poetry. She sat for 10 Lucian paintings, and in the process she learned to enjoy the act of being seen. “I remember the first painting,” she says. “I’d bought this dress in a flea market, and it had an embroidered collar and these clear chiffon sleeves. And he liked it, so that was in the painting. And I felt: he liked how I was.”

I ask what made her a good sitter. “When you are sitting, you’re there completely. I found that I was able to do that, to not be distracted or fidget around. It helped me to find out what I liked about myself.”

The lessons in routine she learned from sitting for her father were useful when, in 2000, she gave birth to her son Jimmy. Last year, she wrote about the moment he was first placed on her chest: “With his black eyes and wet black hair, I thought, ‘I will never be alone again.’” I ask how Jimmy felt when he learned about his mother’s childhood, and she considers the question for a moment. When he was around six, she showed him the film adaptation of Hideous Kinky, “and then I realised it was quite… frightening.” Recently he said to her, “very thoughtful things, like, ‘I admire you so much for what you’ve been through,’” a comment Bella found destabilising.

In 2011, Lucian’s friends and children started gathering to pay him his final visits. He was 88 and dying of bladder cancer, and Bella had been preparing for how she might handle the grief. Amid this sadness, her mother Bernardine, 20 years younger than Lucian and seemingly the picture of health, was told she had a week to live. Bella’s parents had separated when she was two. They died four days apart.

Freud recently popped into M&S, where a woman in her 70s grabbed her arm, laden with clothes from the designer’s new collection. The woman told her: This coat is for me, this suit is for my daughter, and the jumper is for my granddaughter. “One of the good things about being a designer,” Freud says now, “is you can make things for people that help them feel, ‘I’m looking good.’ It’s a huge source of energy. If you feel bad or paranoid about something about yourself, you start to hesitate. I think that’s our service as designers. We can have your back, literally.” The woman in M&S was elated. “She told me, ‘You’ve taken care of all of us.’ And I thought, that’s my job! Being a designer is a service.” As she’s grown into her career, she’s been delighted to discover, quite simply, “I can dress somebody and then send them out, and they can have a good time.”

We walk down into the hushed house, with its rug-strewn couch and, in a glass cabinet, the clothes peg Sigmund used to wedge his mouth open with so he could continue to smoke through the mouth cancer. The graphic novel about him gave Bella access to a history that was made largely of myth. “It’s good to have a container for all that,” she tells me. It helps her think about how to structure her podcast interviews, too. “You need to make it have a beginning, middle and an end.” Her ex-husband once advised her to include “a rattler at about question four or five” of each interview, which, I admitted sadly, I’d entirely failed to do during our interview, instead enjoying our languid stroll through her velvet past.

Freud has been a committed supporter of the Palestinian cause and the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement for many years, and recently joined a number of public figures to call on Keir Starmer to drop plans to weaken human rights law and instead “take a principled stand” on behalf of torture victims. “It’s very disheartening to see how committed to divisiveness our political leaders are and how lacking in vision,” she says. “They seem only to respond to Daily Mail headlines instead of what people need.” She stops. “Although I can’t bear people just going on about how awful everything is! But it’s very catching, all the… against-ness. I find that this obsession with refugees, who they call ‘migrants’, who were people who’ve been displaced, and this terminology of dehumanisation absolutely monstrous. Really, really bad news.”

We stroll through Sigmund’s study, where he worked through 1938 after fleeing persecution in Austria, and gave birth to psychoanalysis, and eventually, miraculously, Bella. “People in fashion are quite political, actually,” she says, pulling her coat on with gentle grandeur. “But no one ever asks them.”

To listen to her podcast, go to bellafreud.com

Hair and makeup by Kelly Orme

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy