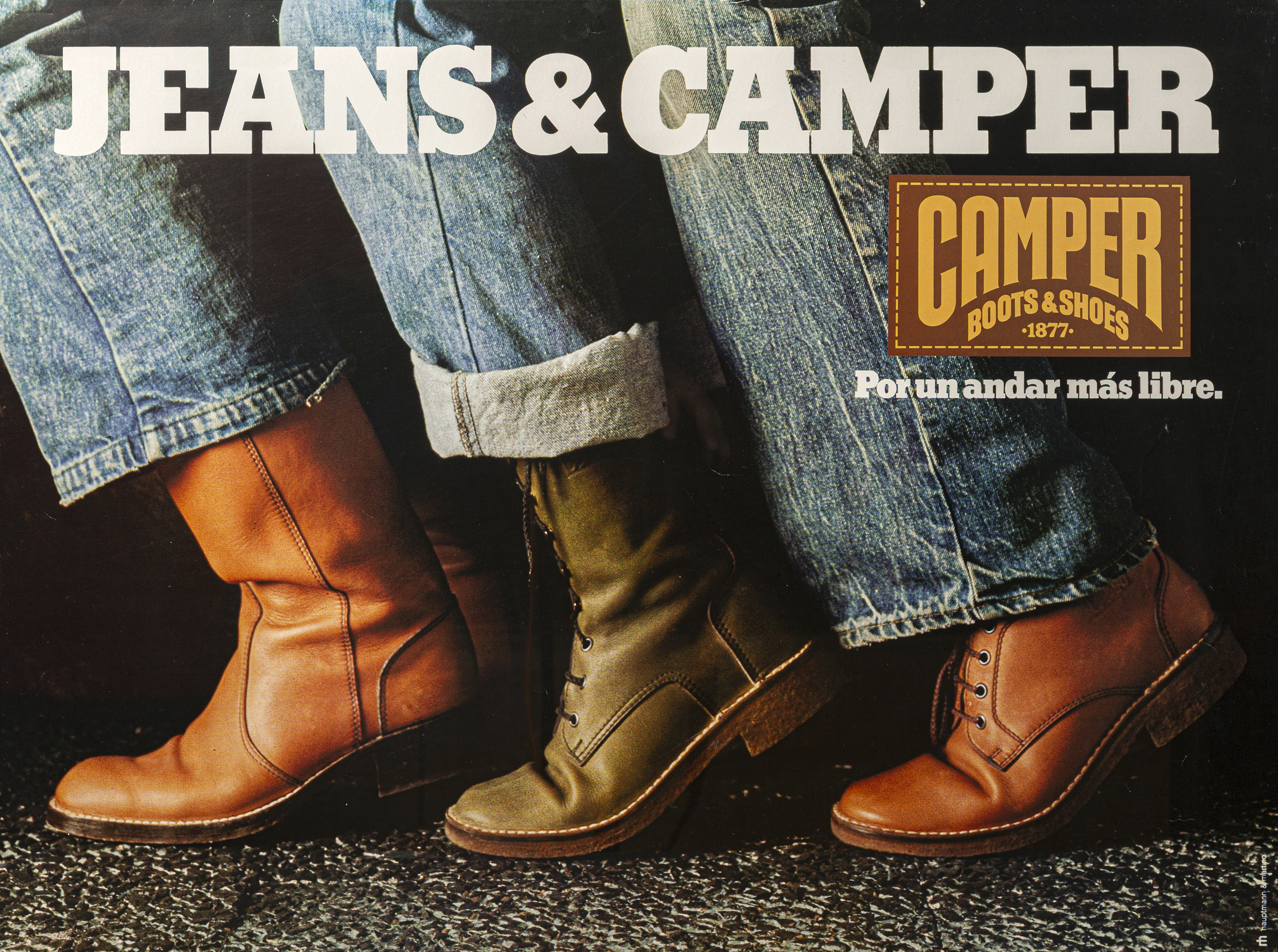

Lead photograph by Martin Parr

The road from Palma to Inca takes you from the Mediterranean coast to the rustic interior of the island. Mallorca may be known as the island of calm, but its third biggest town, Inca, is a scrubby, industrial place, far away from the tourist trail – and the unlikely home of the idiosyncratic, innovative shoe brand Camper.

Miguel Fluxà is the brand’s CEO and on the day we meet, he had woken up to the confusion of Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs. “The US is not such a big market for us,” he tells me in a clean-cut white meeting room in the company’s modern glass and concrete HQ that looks out over snow-capped mountains. “So, that’s kind of OK, in a way.” Camper’s biggest growth markets are in Japan and South Korea; they manufacture in Vietnam, but also produce in Portugal as well as Spain and Mallorca. Even so, his calm response is notable, as is his footwear, a pair of Tossu trainers that, on closer inspection, reveal their unusual construction: a cage-like outer shell over a knitted sock, made from injected TPU, a flexible, rubber-like plastic material, and 3D-knitted recycled PET, all recyclable.

Camper is a family business. Miguel took over from his father, Lorenzo, in 2012. His entrepreneur great-grandfather, Antonio Fluxà, started the first factory in Spain in 1877.

Antonio Fluxà travelled to England – very probably speaking no English – and brought back a sewing machine, and the newly patented Goodyear Welt technique of making high-quality shoes, to the sleepy rural island. “The only industrial revolution that happened in Mallorca was shoe making,” says Miguel. “Actually, it was because of him.”

Today, Camper’s annual turnover is more than €200m with shops in over 40 countries. The brand has expanded to include the quirkily designed Casa Camper hotels in Barcelona and Berlin (Miguel’s uncle Miguel Fluxà Rosselló is the president of Grupo Iberostar, one of the world’s largest hotel chains) and there are plans to open the next one in Istanbul.

The business is still family-run. “We have a very normal family,” says Miguel. He remembers going to the local Jesuit school in Palma proudly wearing his green Twins – Camper’s unconventional mismatched shoes which, for many children, would be a reason not to go to school. “You know, people were looking at me like, ‘OK, are you crazy?’” But Miguel enjoyed wearing shoes that were different.

Like Camper, Miguel is “50 years young”. From the start, Camper treated its branding and communications with the same level of creativity and innovation as its shoes. Collaborators have included the British graphic designer Neville Brody, the artist Javier Mariscal, the beauty artist Isamaya Ffrench, fashion designers Bernhard Willhelm, Romain Kremer and Kiko Kostadinov and the product designer Jasper Morrison. It was Morrison who made a simplified version of the original Camper shoe, the Camaleon, based on the traditional Mallorquin country shoe made from canvas, tyres and string. The latest collaboration, with Issey Miyake, has produced the Peu Form, a development of a Camper classic called Peu (which means foot), a squishy- looking, unstructured supple leather slip-on designed by Issey Miyake’s artistic director Satoshi Kondo.

For the 50th anniversary, Camper invited Martin Parr to capture the spirit of Mallorca for its publication The Walking Society, a large format book and future collector’s item packed with eye-popping Technicolor images of not-so-calm island life. Locals are pictured in familiar Martin Parr seaside territory, taking siestas, bird-watching or with their shopping baskets on the way back from the weekly organic farmer’s market.

Fashion shots of Mallorcan-born film star Rossy de Palma (she named herself after Mallorca’s capital) and New York-based face-of-the-island model Alicia Gutiérrez inject the glamour. Creative director Achilles Ion Gabriel is photographed lying down on his studio desk, wearing an exaggeratedly square-toed pair of Quetal boots, a recent addition to the Camperlab collection.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Gabriel’s first design for Camperlab was the Traktori boot. “I wanted something very Mallorcan, so I thought of farmers, but in the most surreal way,” he says. The resulting boot is a bit like a chunky wellington with a zip down the side and a chunky sole. He developed it into a clog, a Mary Jane and an over-the-knee padded boot that comes in fuchsia pink. “I never think of gender, ethnicity, age or any background when I design. For me, good design belongs to everyone.”

Camper is unusually open-minded in its approach. Junction is a range of shoes that comes with interchangeable colourful rubber toe caps so you can customise your otherwise sensible shoes into something altogether more crazy, while also protecting them from wear and tear.

Last summer, Camper hosted a design workshop for international students and graduates to take part in creative brainstorming sessions led by London-based upcyclists Matthew Needham and Katy Mason at the Finca Son Fortesa, a beautiful farmhouse near Inca owned by the brand. The theme was “Life After Death”. The designers used waste materials including shoe boxes, wooden palettes, old cables, buckets and discarded shoe components to explore different ways to make and unmake shoes. “It’s a good way to experiment. It’s a good way to be in touch with younger generations,” says Miguel.

One of the brand’s early innovations is the Pelotas, now a classic. Since 1995 they’ve produced 11m pairs at the HQ in Inca as well as in Portugal, and they come with a lifetime guarantee. Pelotas means “balls” in Spanish, referring to the 87 rubber balls that make up the sole as well as the stylistic connection to the classic football boot.

While Camper is part of the cycle of overproduction and overconsumption, it seeks solutions to both; the brand has been working on how to make shoes that can be repaired or recycled at the end of their lives, rather than adding to the millions of shoes that end up in landfill each year. In 2000, they produced a shoe called the Wabi. “It was only made out of three parts,” says Miguel. “It was an injected kind of mould, and then you have the insole, and then you have the sock, so one could be recycled, then the other two were biodegradable.” The latest evolution of the Wabi is the Roku, a slightly cartoonish, Flintstones-looking trainer which can be taken apart and – in theory – recycled at the end of its life. “It looks quite simple, but it’s not that simple. There’s no glue.” Instead, the sole is attached to the canvas upper by a complex system of lacing, and inside the upper is a knitted sock. Each of the six components is available to buy separately, meaning you can mix and match colours and customise or repair your own pair. They come with an instruction leaflet, a little like a piece of flatpack furniture.

The catch, however, is that shoes made from injection-moulded foam cannot be processed with your household recycling. Miguel agrees that recycling systems need to be “sorted out on a global level”. But, he says, “At least from the design concept, it’s like, OK, you don’t have the materials mixed. If something breaks, if the elastic breaks, you can buy elastic. So in the end, it allows you to repair it.”

In 2002, Camper ran a campaign designed by Marti Guixé with the message: “If you don’t need it, don’t buy it.” This was almost a decade before Patagonia’s famous “Don’t buy this jacket” advertisement. They also have a scheme in several countries called Recamper, where customers can exchange old shoes for a €30 voucher. The shoes are sent back to Inca where they are cleaned, taken apart and carefully reworked into new shoes which you can buy from the website. Although Miguel says it is difficult to scale, this seems like a good solution to the problem of too many shoes in the world – according to Tansy Hoskins, author of Foot Work: What Your Shoes are Doing to the World, 66.3m pairs of shoes were being made every day in 2018, making a total for that year of 22.4bn pairs per year.

“Nobody needs anything today,” says Miguel. “We have too many things, that’s for sure. We always try to emphasise that we make useful products now, shoes that can be worn, but it’s true that nobody needs anything.”

He also believes in the “positive power of business”. Camper employs around 1,200 people around the world; 300 in Inca. When I ask if repairs and resale of existing shoes with schemes like Recamper will slow down his sales, he shrugs. “I don’t think so. I would be worried if sales reduce because of other things, like we have a bad collection. But if it reduces because people repair their things more, yeah, let’s see what happens. I think it’s a great initiative.”

What’s certain is that a shoe like Roku is a talking point. It makes you think about how multiple materials fixed together with glue are impossible to break down and recycle, and that in itself is powerful. “I think for us in the end, there’s nothing more sustainable than making high-quality shoes that last a long time and that can be repaired,” says Miguel. “It’s as simple as that.”

Photograph by Martin Parr