On a November morning grey as houses, I crossed a bridge over an expanse of railway tracks leading to the Gare du Nord – or away from it, depending how you look at things. Duran Lantink, the young Dutch fashion designer who last year became the creative director of Jean Paul Gaultier, lives in a cul-de-sac backing on to the train lines. In another part of Paris, architects have designed a public park, the Jardin Atlantique, to sit like a lid over a similar network of train lines and Gare Montparnasse itself, concealing its ugliness. But here in the 18th arrondissement, the tracks bisecting the urban sprawl are part of the neighbourhood’s identity, as are the high, graffitied walls surrounding them, and the construction workers smoking and leaning against the glass front of McDo (as the Parisians call it) in tracksuit bottoms and big North Face puffers, and the man outside the Metro selling blackened corn from a shopping trolley, his face disguised beneath a camo cap. Around the corner is a district called Barbès, after which Jean Paul Gaultier named his most famous collection – autumn/winter 1984-85 – and with which he paid homage to the area’s diversity and chaotic energy. “It’s where I feel the most free,” the designer wrote of the neighbourhood years later.

Lantink loves this neighbourhood, too. Right now, most of his life is spent on the seventh floor of the nearby Jean Paul Gaultier studios, leaving him scant time to explore the rest of Paris. But he derives much of his inspiration from this area anyway: between Goutte d’Or and Quartier de la Chapelle, a working-class district with a high immigrant population, the streets congested with day markets selling fruit and vegetables next to unbranded tracksuits and saris. “It’s unpretentious,” he told me, when I met him at his home. “You have these amazing different cultures. And everybody looks really great.”

I asked in what way they looked great, precisely.

“In their own ways,” he said.

Lantink’s home is the largest single-occupancy building on his street. When I visited, the exterior appeared grimy and unloved, a long-dead climbing vine still somehow clinging to the brick wall. But inside was an oasis of sleek lines, chic fittings and open spaces. My first sight of Lantink came from the home’s doorway. Down several steps into an enormous kitchen-cum-living-cum-dining room he was sitting alone on a big grey sofa, smoking a cigarette, totally still.

Lantink received the invitation to become the second-ever permanent creative director of Jean Paul Gaultier in April, and hightailed it from Amsterdam to Paris, putting his eponymous line on hold and bringing with him just a suitcase. (This house came furnished and is not really to his taste; he’d like, for example, to cover up the wall of street art with a white sheet.)

Jean Paul Gaultier, Women, Spring Summer 2026

In October, he debuted his ready-to-wear spring/summer 2026 Jean Paul Gaultier collection at Paris fashion week. Now he’s working on his first couture show and several other future collections. To head a major fashion house is an unrelenting sort of existence and pressure. The rate of production is dizzying. Lantink must design up to five collections a year, along with the shows at which he must display the collections. The pressure is increased by the fact the shows are, at this point, closer to full-on theatrical spectacles than simple runway events.

It’s been an adjustment, especially for a designer who has always danced to the beat of his own drum. Lantink began his career not by designing clothes from scratch but by repurposing pre-existing vintage items and designers’ deadstock into Exquisite Corpse-style creations. As soon as he got wind of major houses introducing repurposed items into their collections, he switched it up again, altering not the clothes themselves (or not just the clothes) but also the body beneath them, padding out garments so that the wearer’s chest or hips would bulge out, distorting the viewer’s expectations of the human form. The route Lantink has taken through the industry is novel: most fashion designers come up by assisting well-known designers. Even Gaultier started as Pierre Cardin’s assistant, though he was only 18 at the time and had had no professional training. In contrast, Lantink turned down all opportunities to assist. “I would find it very hard to work for somebody telling me what to do,” he told me. “I need to be free in the approach I want to take.”

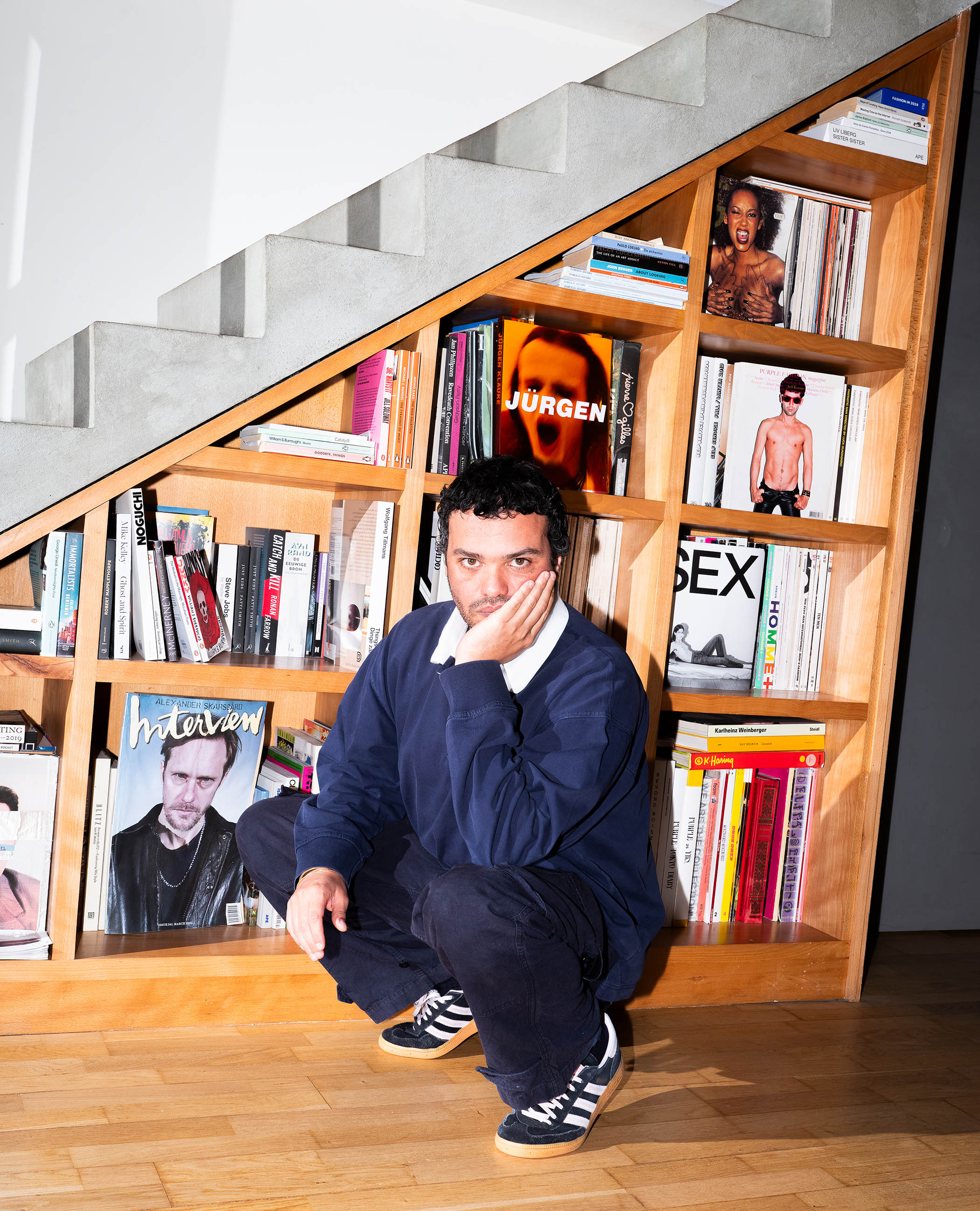

We were talking at a long, polished dining table looking out on to a small, leafy courtyard through glass double doors. Lantink, who is small, was wearing a loose, dark-blue polo shirt, dark-blue cargo pants and Adidas Spezial trainers. He drew his feet up on to the rung of the chair between us so that his body was slightly curved, and crossed his arms over his chest. He has a lovely, open face, and during our time together he laughed a lot, sometimes at my questions though mostly at his own answers. When I asked how he planned to prevent his curiosity and playfulness as a designer from being tempered now that he’s a high-profile fashion figure, he replied, “Obviously it’s harder, and it’s a different platform, but also I’m here to challenge that and find my own way, even though there are certain restrictions,” and he followed the comment with a stream of mischievous laughter.

‘Even in art school people think things should be done a certain way… I had to really fight’

Long before he took the Gaultier job, before he began accruing prestigious fashion prizes – the International Woolmark prize in 2025, the LVMH Karl Lagerfeld Special Jury prize in 2024, the ANDAM Special prize in 2023 – before he launched his namesake label in 2019, before he even studied fashion design in the early 2010s, Lantink would watch in awe as his parents and their friends shed their ordinary clothing at the weekend and transformed themselves into “these creatures that belong to the night”, destined for the clubs.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

He recalls seeing them wearing gold and silver catsuits (in Junior there are gold-sequinned coats and gold bikinis, subversively inflated). He remembers a white muslin Margiela dress (in Junior there’s a floaty, white-pleated dress, but the front sticks out to reveal a Breton-striped leotard with straps running down the legs that connect to Breton-striped socks, a nod to Gaultier’s endless reworking of that French staple, the marinière top). He remembers, even, someone wearing the ruched-velvet, cone-bra dress from Gaultier’s Barbès collection, which remains one of the designer’s most iconic designs. (In Junior it is reimagined as an orange catsuit, the bullet bra protruding not outwards but sideways.)

Lantink wanted to begin his tenure at Gaultier by paying tribute to these moments from his early life – all those adults in his childhood home in a state of glamorous metamorphosis – because it was then that he first recognised how fashion could offer you access to another life and another world. It’s a cliche to say that knowing you are gay as a child can make you feel like an outsider, but it can also feel liberating, Lantink told me, because it emboldens you to go out looking for a world that isn’t really here yet. When he said this, he reminded me of the theorist José Esteban Muñoz’s characterisation of “queerness” as a category that cannot exist “here and now” (the “here and now” Muñoz terms a “prison house”), but always “then and there” – a horizon towards which we must strive.

Jean Paul Gaultier, Spring Summer 2026

Lantink always seemed to strive towards the horizon. He was a punky kid with piercings and, at times, a pink mohawk who sometimes wore his mother’s dresses to school. He began experimenting with collaging clothes when he was 14. Rather than letting his stepdad throw out his old Diesel jeans – a potential tragedy – Lantink cut them up and made them into belts. Then he asked one of his schoolfriends’ mums, a talented seamstress, to stitch together the belts with strips from his grandmother’s plaid tablecloths, turning them into skirts. His grandmother also helped with the sewing for his early creations. “Do you like this?” he would ask her, and she would always reply evasively: “I think it’s special…”

Lantink laughed recalling the memory. “It’s the story of my life!”

With industrious spirit, Lantink took the skirts to a steampunk-adjacent Dutch retailer who agreed to stock them, and they sold out immediately. Off the back of this win, he thought it would be cool to organise a fashion show. His friends were all tall, skinny kids who wanted to model, but were too young. One of their parents ran a beach club in a small town outside the Hague, and they held their catwalk on the club’s terrace, all of Lantink’s tall, skinny friends parading up and down in the chimerical garments he had been constructing.

When Lantink finished school, he briefly attended the Amsterdam Fashion Institute before deciding the college’s attitude to fashion was too traditional. “It was terrible for me,” he said, “because it was very much a system.” His conceptual approach was better appreciated at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, also in Amsterdam, where he enrolled in 2010. Nevertheless, he was still always having to justify his preference for assembling work out of pre-existing clothes, like a Frankenstein with many monsters, rather than making clothes from scratch, as the other fashion students did. “Even in art school, there are people who think traditionally, and they think that something should be done in a certain way, because they are used to that. I had to really fight in the first two years to push through the way I like to work and the way I see myself evolving.”

At his home, Lantink told me he had been thinking a lot about validation recently. You will not survive as an artist if you don’t have someone in your corner who actually believes in what you’re trying to do, he said. Lantink was lucky to find such a person in Niels Klavers, who turned up as head of the fashion department at the Rietveld academy in Lantink’s second year. Klavers recognised that Lantink was instinctively working at the cutting edge of fashion, advocating for reuse at a time when such practices were not common in the industry. Klavers was the first person who really appreciated what he was doing, Lantink said, and told him to keep pushing forward with it.

‘I would find it very hard to work for somebody telling me what to do. I need to be free in the approach I want to take’

Klavers and I emailed back and forth after my meeting with Lantink. He described the outfits Lantink constructed at art school as “mind blowing”. He sent me a link to the 2013 Rietveld graduation show, in which Lantink’s was the closing collection. (Just recalling it now gives him goosebumps, Klavers told me.) The collection already contained elements that now feel quintessential to Lantink’s design style: one model wore an outfit that had been cut in half, then stitched back together with a see-through plastic panel over a pale stomach; another model, clad all in white, wore drag-style 80cm, 3D-printed acrylic heels covered with various religious symbols, and was wheeled in at the end of the show on a high white podium.

The event was performative and playful, but it was also the work of someone who seemed to have already formed a coherent and totalising vision for what they were trying to achieve. Later, over email, Lantink told me that while coming up with his graduation collection, he had been fascinated by how design choices can place limitations on function. “When a person wears the 3D-printed shoes, walking becomes impossible, so they must be carried,” he told me. It was the impracticality of 3D-printed skyscraper heels that allowed the show to end in the most unusual way, with models ceremonially rolling their otherworldly wearer across the stage.

For Lantink, limitations are not a hindrance but an opportunity to be steered in new directions. His first standalone Duran Lantink collection show took place in the midst of the pandemic in 2021. “It was an amazing opportunity for me,” he told me. He couldn’t produce a show in person, which allowed him to become more inventive. He came up with the idea of filming the show with drones that viewers operated themselves remotely. That way, he said, “I could create my own world.”

Out in the courtyard, a glimmer of sunlight appeared among the trees. Lantink went to fetch a gold ashtray, then lit up another cigarette. Junior was shown in the industrial basement of the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac. Several hundred metres away, the Eiffel Tower sparkled enticingly. He might have chosen the tower as a runway destination, but he decided instead to take his audience underground, a decision that reminded me of those two possible architectural responses to the sight of the railway lines that run through Paris: do you cover them with a facade, or do you embrace them, warts and all?

Lantink’s Junior collection produced delight and excitement in the fashion world. Vogue’s Nicole Phelps told me that it didn’t look like anything else she’d seen this season, “and I think that’s Duran’s speciality. He’s fearless.” But it also sparked outrage and subsequent fears that Lantink would never live up to Gaultier’s legacy. (Gaultier himself was very moved by Junior: it felt like a recovery of the “old energy” that coursed through his early collections, he said, and he reminded people that he too had courted a fair amount of controversy when he began working.) When I asked Lantink about the negative reaction he received to his first collection, he seemed unfazed. If anything, he said, he was pleased his work had stimulated conversation.

Felice Noordhoff walks the runway during the Duran Lantink Ready to Wear Autumn/Winter collection as part of Paris Fashion Week 2024

The main target for condemnation were the collection’s skin-tight bodysuits printed with hyper-realistic nude male bodies, resplendently hairy and well hung, worn both by male and female models. Was it anti-feminist? Was it a joke? If so, at whose expense? When I asked Lantink how he came up with the idea for the bodysuits, he let out a long whistle. They began with Gaultier’s predilection for trompe l’oeil – clothing as optical illusion – such as Gaultier’s tops printed with hyper-realistic tattooed and pierced naked torsos, or his bodycon dresses printed with overtly sexy naked women. And then Lantink started thinking about Borat…

“You know, the guy with the thong, super hairy?” he asked.

I knew the guy, I said, though I added that I hadn’t expected the Sacha Baron Cohen mockumentary to pop up as a reference for a Gaultier show. (It made me like the hairy bodysuits even more.)

Lantink continued. One day, his team had found a T-shirt printed with a hairy torso on Amazon, and they decided to use it. On social media, critics later described the collection pejoratively. Many said the bodysuit looked “as if it were from Amazon”.

“And they were absolutely right,” Lantink said, smiling naughtily.

Lantink decided to extend the T-shirt into a bodysuit, because it thrilled him to imagine a woman walking down the street wearing, as he put it, “dick leggings”. “I wouldn’t think shock-factor,” he told me. “I would think: ‘Ahh, yes!’” When the New York Times responded to the hairy bodysuits by declaring that “provocation for provocation’s sake is just puerile”, they were missing the point. Lantink’s aim is to expand our conception of what is possible and appropriate in today’s society. By creating garments that allow the wearer to perform, in the crudest way possible, another gender, he might awaken audiences to the performative nature of gender more broadly.

Gaultier blurred the line between what we think of as male versus female clothing. Now Lantink wants us to question the boundaries of gender itself. You might say this is a facetious, even anti-intellectual way of going about it. But I’d call it exciting that someone is choosing to make these kinds of risky, irreverent statements on the fashion world stage at a moment when gender-nonconforming bodies are facing so much hostility.

Naturally, Lantink wouldn’t share plans for his next collection. Recently, though, he’s found himself wanting to explore once more the hybrid, cut-up approach with which he began his career. I asked him whether he had seen anyone cutting up his own designs to make them into something new.

“No,” he said, “but I would fucking love that!” He was practically fizzing with excitement. “I mean, some students have my archive now. I would be very happy if that happens.”

Jean Paul Gaultier, Women, Spring Summer 2026

His belief that fashion ought to function as a cycle in which nothing is ever lost extends to his own work. He is both confident and egoless enough to take pleasure in imagining his designs being destroyed so that something new might grow from their ashes.

During our conversations, Lantink frustrated my expectations of a fashion designer. I had assumed that the symbiotic relationship between designers and the hyper-wealthy patrons of their houses would cause them to become more detached from reality. But Lantink seemed absolutely grounded. When I attempted to describe him afterwards to my (mostly fashion-illiterate, mostly fashion-cynical) friends, I always opened with the same story, which I think demonstrates best what makes him particular.

Between his undergrad and his master’s, Lantink and his friend the photographer Jan Hoek received funding from the Dutch government to travel to Cape Town. There they met Sistaazhood, a self-organised trans community of sex workers, with whom they started collaborating. They ran workshops and designed outfits and runway collections together, paying the Sistaazhood to model for them.

They created a Dream Collection, for which the women could suggest their dream fashion looks, and then Lantink would endeavour to create them. One woman wanted to be Victoria Beckham, but if Victoria Beckham were also a drug dealer in Miami. Another decided to be the Statue of Liberty’s fire. Lantink was especially animated and expressive when describing how they went about curating these dream looks, with minimal resources. It felt as if he were offering the truest representation of a fashion designer’s role: to liberate the fantasies of others.

The collaboration with Sistaazhood lasted five years. “We haven’t seen them for a couple of years,” he reflected, before reaching for a final cigarette from his packet. “It doesn’t feel right.”

After he told this story, I left him alone in the courtyard, where he sat smoking, totally still as he had been when I arrived, in a brief window before his next appointment. And then I was back out in the 18th arrondissement, alongside the railway tracks, among all those people dressing in their own ways.

Images by Yannis Vlamos; Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images; PPS Backgrid; Alamy