Photographs by Joshua Bright

In the summer of 2019, shortly after a Russian act of aggression against Ukraine in the Kerch Strait, I stood in a Moscow hotel room and chose a blouse to wear. It was of vivid blue linen, and embroidered with floral motifs; its neck and sleeves closed with tasselled drawstrings. Once dressed, I made my way down to Red Square and wandered about the perimeter. Now and then passersby looked me up and down impassively, but I’ve often been too tall and stately to pass without notice – my clothes too noteworthy or strange, my hair grown out in heavy, whitening sheaves or shaved to the scalp – so I was untroubled, if uncertain what to make of their glances. Back at the hotel, a Russian journalist waited to speak with me about my latest novel (which deals, as it happens, with personal culpability in state atrocity), and as she poured black tea she looked acutely at my blouse. “I’m sorry,” she said, “but do you know what you’re wearing?”

“Of course,” I said, and gave the correct term for the embroidered clothing which is as distinctively Ukrainian as a kilt is distinctively Scottish. “This is a vyshyvanka blouse. I’ve always worn clothes like this. But clothes aren’t neutral, they’re never nothing: for women in particular it’s always been a way of showing politics.”

“And you wear it now? Where have you been?”

“It was a long flight,” I said, “so I went to stretch my legs just over there” – I gestured towards Red Square. We spoke for a time about the suffragettes’ coloured sashes, and the red ribbons worn by Frenchwomen to signal pity for victims of the guillotine, then moved on to other things; and though I thought little more of it I was amused to find my fondness for vyshyvanka clothes noted in the newspaper. Now the war on Ukraine is in its fourth year, and that blouse has been lost and replaced by another – this one antique, its hand-embroidered cotton worn thin – and once, as I wore it through the city where I live, I was stopped by Ukrainian women surprised and delighted by what they saw.

I have been in love with clothing all my life. I measure out my years in yards of printed cotton, in bolts of linen and silk; it’s never the scent of cake that recalls times past for me, but the drape of a skirt. Say it’s Christmas, and I am eight years old – I wear a dress in brushed cotton smocked by my grandmother, its collar bought by my father from a lacemaker in Belgrade. Then I’m 12, and my mother gardens on a fine day in a short-sleeved shirtwaister in faded apple green: I ask if I can have it when she dies. Then abruptly I’m 16, and baptised by immersion in a chilly chapel – I’ve sewn weights into the hem of my sober dress to prevent it rising in the water, and afterwards change into a top in rough fabric of forget-me-not blue.

I look back, and see dresses on the path behind me as if I had shed them as I walked. Some by now are indistinct; others appear in no less detail than on the day they were made or worn. From a distance of almost 30 years, I make out, for example, a length of blue velvet, and recall hours in a cold bedroom sewing myself a dream of beauty to wear to the sixth form prom. I’d never been to any kind of party which might entail music or dancing – that wasn’t the done thing for members of the chapel my family attended – and exulted at this opportunity for extravagant dress, but there were difficulties. This was the 90s, when ideally a woman should display a pelvis sharp enough to cleave firewood, and meanwhile I had the broad-hipped body of an Edwardian music-hall star. Besides: I had no money. So – thanking God I was descended from a long line of dressmakers – I sewed a dress myself: square necked and empire-line, the velvet £4 a yard from a Chelmsford market stall, the bodice sewn all over with blue-black beads like fragments of beetle. At about this time I coveted the Fendi “baguette” bag, which was both the height of 90s chic and incomprehensibly costly – so I made my own from offcuts of velvet, painstakingly beading the interlocking “Fs” which constitute the Fendi logo. I felt rather foolish in that dress, drifting among slender girls in tight black frocks and vertiginous heels; and it is perhaps because of this that many years later I bought myself a Fendi bag, and – taking it reverently from its butter-yellow box – felt I was handing it through time to that girl forever pricking her finger with the needle.

The study of clothes is no less noble than the study of architecture, or botany. Its language is polyphonic

The study of clothes is no less noble than the study of architecture, or botany. Its language is polyphonic

Though I’ve never mastered the art (I keep a suitcase in the attic full of noble failures I can’t bear to throw away), I have sewn all my life with the lunatic optimism of the alchemist, transforming the base metal of fabrics into gilded dreams of beauty and strangeness and power. During the pandemic, when it seemed absurd to think I’d ever have cause to be seen in such thing, I had six yards of cotton printed with a painting by the Dutch master Otto Marseus van Schrieck – an unsettling, unstill life of cyclamen and lizards on a green-black ground – and made this into a dress with a full and curiously structured skirt, a narrow waist, and a scooped back cut to display the tattoo on my spine. Summoned recently to a black-tie event in Atlanta, and having by now developed such refined tastes I could find no gown I liked for less than a king’s ransom, I set aside my manuscripts and turned again to my sewing machine. I scoured the internet for precisely the silk I required (black moiré, which is to say pressed between heated rollers until it resembles moonlight on rippled water), and made the only dress of which I’ve ever been proud, though it wouldn’t escape my grandmother’s expert eye unscathed: its full skirt is drawn in minute gathers to a tailored waist, and it circles my bare shoulders with a folded band; its bodice is lined in silk chiffon stitched invisibly by hand into the seams. In it, I appear as I wish to be seen: bewilderingly poised between Moll Flanders, and a bereaved Victorian housekeeper.

Often, clothes have represented for me the promise of joy when life has brutally withheld it. One autumn, as I watched a family member die of cancer at shocking speed, I bought myself a coat by the designer Walid al Damirji, constructed – like all his clothes – from antique cloth, lending the virtue of sustainability to the pursuit of style. It is breathtaking to wear and behold, its shining embroidered silk almost insolently opulent; I felt no guilt when I bought it (though possibly I ought to have done), only a sense that our lives are briefer than we ever take them to be, and that if possible nothing should be forestalled, still less kept for better days that might never come. Now – as if out of gratitude for extending beauty as certainly as if he’d opened a window in a bleak sealed room – I have become Walid’s devotee; and when in due course I recently finished working on a manuscript about that time of dying, I bought a dress to match the coat, and its yards of turquoise floral linen – softened by time – feel to me like a blessing.

It’s a mistake to think a love of clothes is merely a preoccupation with fashion, or even with beauty. It is a question of narrative, and I dress in the same spirit in which I write – with language, metaphor, and sleight of hand. Say I must persuade a doctor to give me a course of treatment; I might tell in my clothing the story of a woman who matches a GP’s intelligence, but (vital stuff, this) will submit to their expertise – a woman courageously tired, though with no indication of poor mental health. I’d choose then a pair of brogues, and my handmade Bonfield coat in pale brown wool, the neck unbuttoned to show the frill of a cream silk blouse; a single ring possibly, though nothing flashy (one must be alert to the balances of power). A mature woman, this: something sensible in those shoes, something charming in that frilled collar, though possibly there’s mischief in that ring with its silver skull: the appointment goes well, though I cannot say whether it is because I have signalled my virtues with my clothing, or because I think I have.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The writer Sarah Hall, sharing my love of clothes and attention to its narrative potential, took me recently to Castlerigg, a neolithic stone circle set in a theatre of Cumbrian hills. Laughing, we’d conferred on our outfits: who would we be that day – cocky boys traipsing in peaked caps perhaps, or witches with their pockets full of tarot cards? In the end, I wore a corseted black velvet coat by Renli Su over a striped dress with sleeves gathered at the wrist; Sarah chose a tweed jacket tailored to the waist over a long linen dress by the Swedish maker Nygardsanna, and soft leather boots that buttoned to the knee. The effect (as we well knew) was that we seemed to have arrived, through a thin place between the stones, out of a vanished Edwardian spring, and were gratified and amused by how other walkers in their North Face fleeces paused to take a look.

Occasionally, I dress as a means simultaneously of aggression and defence, buckling myself in like Joan of Arc in her breastplate and greaves: if I’m especially nervous I will bring out the Margiela Tabi shoes, which give the effect of a cloven hoof, and are nauseatingly odd or dauntingly chic according to your fancy. With these I might wear the coat made for me by IA London, with shoulders that open like petals at the seam: inscribed on the hem beneath a pattern of blotted scarlet roses are the words KEEP YOUR MIND IN HELL, AND DESPAIR NOT. Frequently, I dress to confound, and thumb my nose to the patriarchy’s expectation that I should whittle myself down and assert the smallness of my waist. Many of my clothes are so voluminous that the body underneath might vary by several stones in each direction, and they amplify my presence to a yell when a woman’s body is expected to whisper: dresses from Egg Trading constructed with extraordinary skill from yards of stiff brown taffeta or partially transparent linen, or the dress made by Lemuel MC from offcuts of deadstock silk for men’s ties, with puffed shoulders that do nothing to diminish me to a respectable size. Still, my mistakes are numerous and excruciating to recall: uncertain what to wear for my PhD viva, I made a black skirt banded at the hem with yards of coloured ribbon, and throughout the exam – the examiners regarding me with eyes like drill bits, and frequently getting my name wrong – I felt its romance exposing me brutally to their disfavour.

I dress in the same spirit in which I write – with language, metaphor, and sleight of hand

I dress in the same spirit in which I write – with language, metaphor, and sleight of hand

Possibly you think me frivolous but you cannot absent yourself from the language of fashion – the attentive observer will note whether your jeans are bootcut or skinny or tapered or cuffed, whether your trainers are Vans or Converse or Nike, or unbranded out of discretion or economy. To refuse an interest in clothes is to show interest in them – there’s often more pride in a thoughtless outfit than a considered one. The study of clothes is no less noble than the study of architecture, or of botany: its language is polyphonic and figurative, its history broad and deep and not infrequently violent. Take, for example, the ubiquitous summer dress with its shirred bodice and full sleeves: it is the echo of smocks worn by English farmers, and of late Victorian leg-o’-mutton sleeves. Is the fabric floral? Well, then: it has arrived in Europe courtesy of the East India Company, and there’s blood in that pretty print. Are the seams frayed, pinked, overstitched, taped, or French; the skirt gored or gathered or tiered? Dwell on it too long, and you go a little deliciously mad, scouring the world for the distinctive turn of a cuff. Once on a London bus I saw a man in what resembled the clothes of a 19th-century exquisite handed down through generations of sons: a rumpled frock coat, a stand-collar long-cuffed linen shirt; a fraying bucket hat, and brogues upturned at the toe – and knew at once that he was dressed entirely in Paul Harnden, a designer so prized, so costly and so remote it’s considered bad manners even to acknowledge you have recognised his work, and I thought of him with envied awe for days.

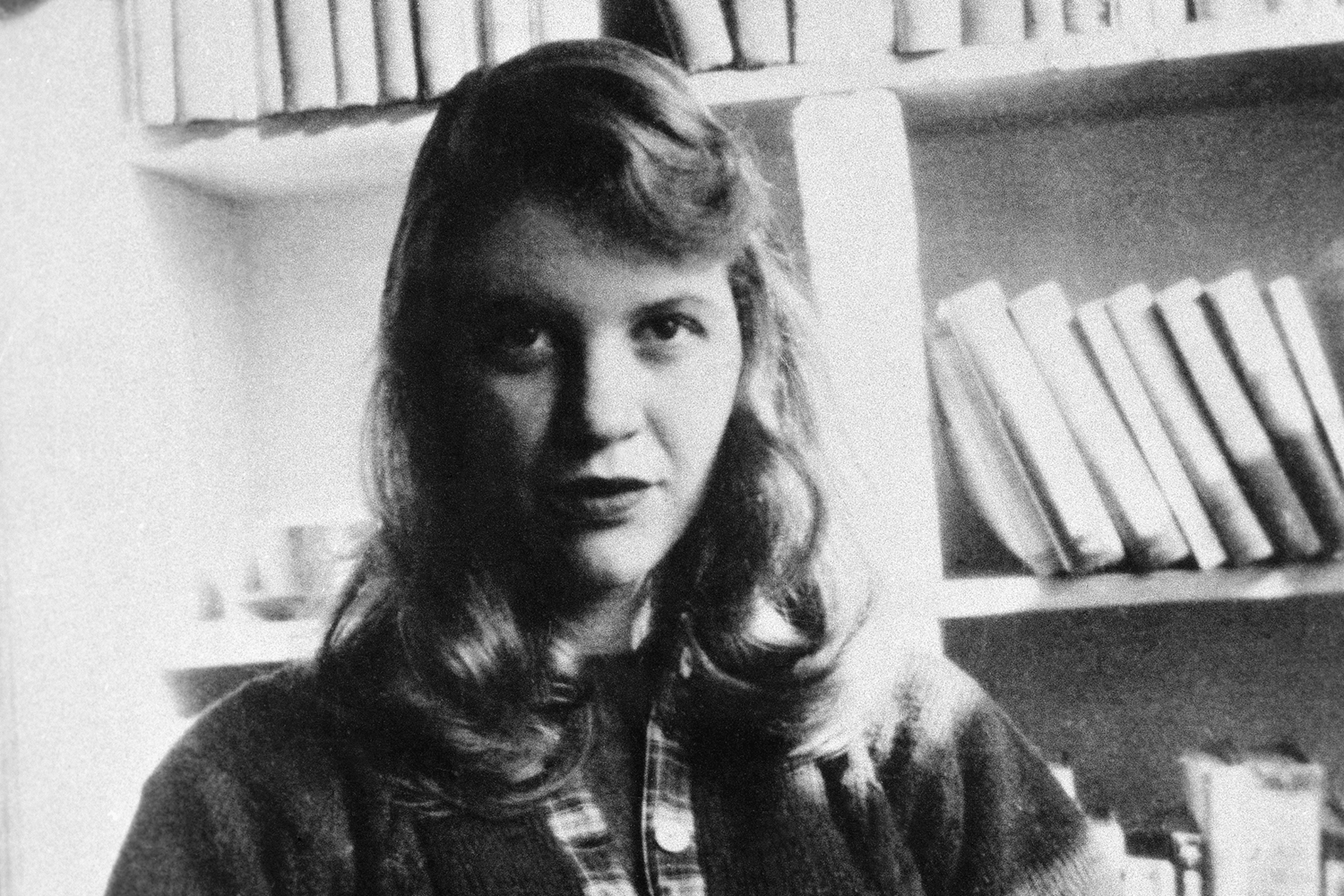

Often, it occurs to me that in fact I care more about clothes than I do books – that my stockings are not blue but silk, that I nullify my intellect with taffeta and velvet. Then I console myself that writers have frequently been associated with style – though it’s not the usual customers, however I venerate them, who seduce me most. Sylvia Plath was pretty, Joan Didion was thin: so what? There’s no skill and certainly no risk in happening to possess genetic traits that align with social aesthetic standards. I’m infinitely more moved by Hilary Mantel’s capes and kaftans, draping in chiffon or cloth-of-gold the body that gave her so much pain; by Audre Lorde’s insouciant stance in her tunics of Ankara waxed cotton. George Eliot – once bitchily described by Henry James as “magnificently ugly, deliciously hideous” – disliked her own appearance, but nonetheless acquired clothes that increased in opulence as she increased in affluence: a mantilla of black lace; a wasp-waisted gown of midnight blue taffeta embellished in beads and ribbons and braid. Virginia Woolf in Orlando wrote: “Vain trifles as they seem, clothes … change our view of the world and the world’s view of us” (and she was forever anxiously buying hats).

After I left Moscow that summer, I travelled to Tolstoy’s estate, Yasnaya Polyana, where at the conclusion of a literary festival, and at about midnight, I was invited by a group of Russian women to swim in the lake. We walked through Tolstoy’s orchard picking apples, and when we came to the water I took out my swimming costume and was greeted with laughter: whatever was I doing, putting on clothes to swim? After a little persuasion and a lot of the vodka they’d brought, I stripped off and slid down the muddy bank. Now and then we spoke to each other; largely we drifted apart in peaceful solitude. The moon was heavy and full, and struck the vodka bottle and the apples on the shore; without embarrassment I saw my body rise above the untroubled surface of the lake. It does not escape me that for all my lifetime’s pursuit of the perfect fabric in the perfect cut, I have perhaps been most contentedly myself among strangers whose names I don’t recall, and wearing only water.

‘Clothes are never neutral’

“Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than merely to keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us”

“Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than merely to keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us”

Virginia Woolf, Orlando, 1928

“Why can’t I try on different lives, like dresses, to see which fits best and is more becoming?”

“Why can’t I try on different lives, like dresses, to see which fits best and is more becoming?”

Sylvia Plath, The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath, 1982

“The list enabled me to pack for any piece I was likely to do. Notice the deliberate anonymity of costume: in a skirt, a leotard and stockings, I could pass on either side of the culture”

“The list enabled me to pack for any piece I was likely to do. Notice the deliberate anonymity of costume: in a skirt, a leotard and stockings, I could pass on either side of the culture”

Joan Didion, The White Album, 1979

“I want to look into my wardrobe and know the truth: that seasons change, and spring comes back again and again and is always filled with colour and pattern”

“I want to look into my wardrobe and know the truth: that seasons change, and spring comes back again and again and is always filled with colour and pattern”

Zadie Smith, Vogue, 2024