I ’ve never been so deeply moved by a heap of shit. There it was, carefully aimed at a small bush and then spread out by massive scrabbling feet, the better to advertise the male who let it fall. To me it was the Hallelujah chorus remastered in coprological form.

It wasn’t just because it came from a black rhino. It came from a black rhino in the great, glorious, beloved Luangwa valley in Zambia. I first came here in 1989, and left a piece of my heart beside the Luangwa river. Ever since then, I’ve come back whenever I could to reconnect with it. So there I was once again, co-leading a trip with Wildlife Worldwide and pointing out hourly wonders.

Before this magic moment, I had never seen unmistakable evidence of rhinos in the valley. Rhinos went extinct here in the mid-1990s; when I first arrived, they’d only just been removed: poached to feed the ludicrous trade in rhino horn. There used to be 4,000 of them.

The prime reason for most local and global extinctions is the destruction of habitat: cut down, ploughed up, concreted over. That’s not the case here. The valley has miles and miles of perfect rhino habitat. The habitat hasn’t gone; just the rhinos.

There are two national parks in the valley: South Luangwa National Park, which is 9,059 sq km; and North Luangwa National Park, which is 4,636 sq km. Both are mostly surrounded by wild Game Management Areas. There’s plenty of wooded savannah here, on either side of the Luangwa river, which flows undammed and uncanalised for 770km from the Mafinga Hills to the Zambezi.

The South Park is well visited, especially round the bridge at Mfuwe, and it offers some of the best wildlife-viewing in Africa. But the North Park is remote: it receives just 500 visitors a year, who mostly arrive in light aircraft. I first reached it in 1992, when there were no roads and no option but to walk everywhere.

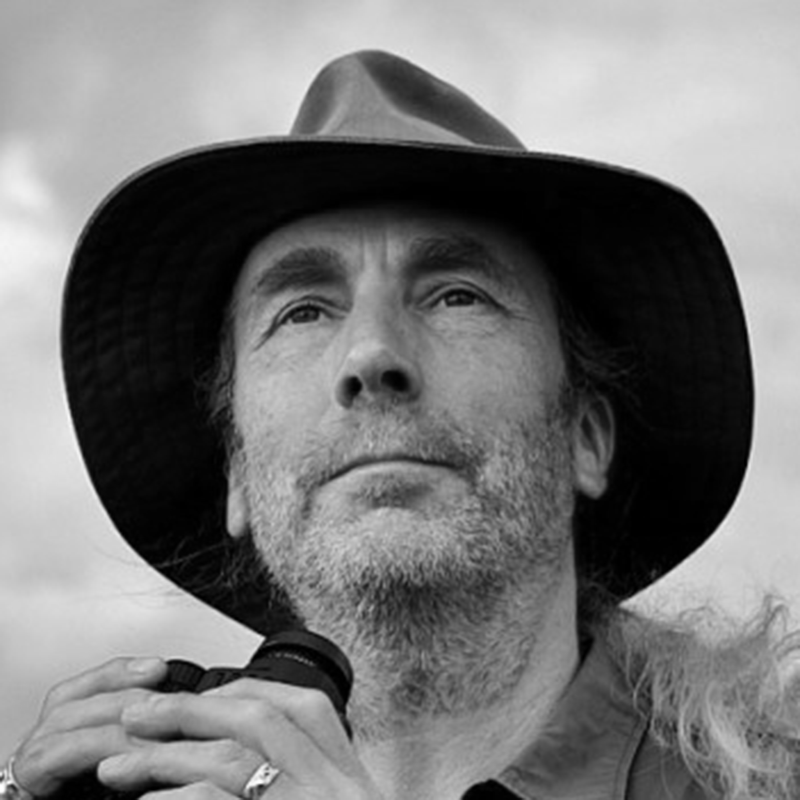

A black rhino in the Luangwa valley

It was around that time that a mad idea somehow germinated. Let’s put black rhinos back into the North Park. And, crucially, let’s keep them safe.

The threat to rhinos is dizzying in its extent and dismaying in its idiocy. In traditional Chinese medicine, rhino horn is used to treat fever, pain, rheumatism and convulsions; laboratory tests have shown that it does absolutely nothing. Perhaps the cost makes it work as the ultimate placebo: it is sold for up to $60,000 a kilo.

This has led to a more exuberant interpretation of the value of rhino horn in Vietnam as new prosperity sends its richest people deliriously giddy. They use it for just about anything, from curing hangovers to relieving cancer. It’s also considered the ultimate prestige party drug. But rhino horn, like your fingernails, is made from keratin.

Across the world, one rhino is poached every 15 hours, mostly from South Africa, where many are in private hands. The trade is banned internationally; in South Africa and Zimbabwe, people claim that a legal trade would be good for both humans and rhinos. Others believe that increasing the supply would only widen the market for poached animals. But there’s one certainty: every rhino project in the world is dauntingly difficult.

The North Luangwa plan is operated by Frankfurt Zoological Society in partnership with Zambia’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife. The first step was the establishment of a headquarters in the North Park, involving small fenced enclosures called bomas and a wider fenced area for eventual release and containment.

Also a serious airstrip. In 2003 five pioneer rhinos arrived by Hercules aircraft, each inside a packing case. John Coppinger, owner and founder of the safari company Remote Africa Safaris, was there to witness the great moment. He was asked to help with the first of these and to release its massive contents.

“I was all choked up,” he remembered, still with some surprise in his voice. “The first rhino to set a foot on the Luangwa valley for a quarter of a century...”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The Famous Five settled in and were later released from their bomas o roam the park. In 2006 another 10 arrived, followed by two more lots of five in 2008 and 2010. Eight years later, two more males arrived to refresh and deepen the gene pool. The fenced area they live in has been expanded: it’s now 1,300 sq km. Mwaleshi Bush Camp, where I was staying, is within the fence, which is thigh high to a human and electrified: all terrestrial species except elephants can get over it or under it.

And here is the truly miraculous part of it: so far – it’s hard to type while touching wood, but I’m doing my best – not a single rhino has been lost to poachers, and while we’re at it, not a single elephant either. The rhino population is now between 50 and 100 individuals; about 50 rhinos have been born in the Luangwa valley since 2003. Which is one hell of an improvement on nought.

I spoke to Ed Sayer, conservation director for the Frankfurt Zoological Society in Zambia. “The [droppings] you saw around the Mwaleshi river,” he said. “There are two bulls associated with the area, both them born and bred in the Luangwa valley. There are also six cows.”

We found tracks on the dusty floor of the dry season floodplain: triple-toed, looking like the ace of clubs with an unusually thick stem. Rhinos had walked here the day before, going about their daily business. They’re hard to see: black rhinos are browsers rather than grazers, and like to strip bushes of their leaves in thick scrub – dry and forbidding places at this time of year.

So there I was, breathing the same air as a rhino – and doing so in my beloved valley. Rhinos have died since the project began: often enough from combat, because they relish a good punch-up and can take it to the mortal level when equals meet. But every death has been natural and every body recovered still had its horns attached.

“The community is our greatest asset,” Sayer said. “We employ 400 people and 98 per cent of them are local. The more the community is connected to the project, the better chance the rhinos have. The project works for the socioeconomic development of the area: and conservation is the biggest employer. The community is involved in decision-making. It just wouldn’t be possible to make this work without community engagement.”

They have to withstand blows to the safari industry, another significant employer. These came after 9/11 and the consequent American reluctance to travel, and then the two-year disruption with Covid. But the rhino project has carried on, though not without hiccups.

Simon Barnes is a trustee of Conservation South Luangwa UK

In 2021, a rhino managed to cross the fence, quite a feat in itself, and set off on his travels. He went down south, by which time he was known as the walkabout male, and a decision had to be made. He travelled 220km, apparently quite comfortable in a part of the South Park where there are no roads. If he stayed there he would be poached: so a rescue was launched. This involved two helicopters plus aerial surveillance from the excellent local NGO Conservation South Luangwa.

Rhinos have been transported by helicopter before, darted and unconscious, travelling beneath in a sling, all four paws in the air. But it had never been done over such a distance. The journey was undertaken on April 8 2022, with two stops for veterinary examination, relieving the pressure on the rhino’s legs and refuelling the helicopters. Eventually the animal was lowered to the ground for the third time, this time into a boma back in the North Park – and he recovered and was later released back into the park, where I trust he is siring his fair share of young rhinos. Certainly he has enough travellers’ tales to fascinate any potential admirer.

The fight against global and local extinctions continues all over the world, in the face of an ever-increasing human population with ever greater demands on resources. In the Luangwa valley, a massive local extinction of a massive once-local animal has been put into reverse: a massively heartening achievement.

And for me there’s a deeply personal element. I spent two months living in a hut on the banks of the Luangwa river on a reckless unilateral sabbatical: the place is part of me and in the course of my many returns, I have seen and heard and smelt and experienced a million wonders.

Sit down with me around a campfire, pour me a glass of whisky and I’ll tell you tales of lions and elephants, buffaloes and leopards: four of the famous Big Five. I never exaggerate, for I have no need. And now I can add a story about a rhino – the last of the Big Five. Just a scattered, scrabbled aromatic pile of glory, but as wonderful as any other tale I might tell. Or perhaps even more so, for I have seen extinction itself work backwards.

Simon Barnes is a trustee of Conservation South Luangwa UK and a patron of Save the Rhino

Photographs by Edward Selfe, Nature Picture Library/Alamy, Chris Breen