This is a story told in four scenes over 30 years. Scene one starts in Manchester, in 1995.

It is the last weekend of May. The phone rings. It is my brother calling. He never calls so it must be serious. It is. My father has had a heart attack. I need to come immediately to the hospital.

I was 23 years old and had been living in Manchester since leaving home to study at university. In the six years since I had left Luton, I had only returned when the guilt became overwhelming. I had chosen to study in Manchester because I wanted to create as much physical distance as possible from my father to reflect how distant I felt from him. My father, Mohammed Manzoor, had arrived in Britain from Pakistan in early 1963, and even though I was fascinated by the 60s, it never seemed to occur to me to ask my dad what his experience of them had been. Why spend time talking to your dad about his old stories when you could be going to clubs and gigs?

I put the phone down after talking to my brother and called my friend Paul Vine-Jones, who drove me from Manchester to Luton and Dunstable hospital. I arrived there to see my father in a coma from which he never woke. He died on 6 June 1995. I turned 24 three days later.

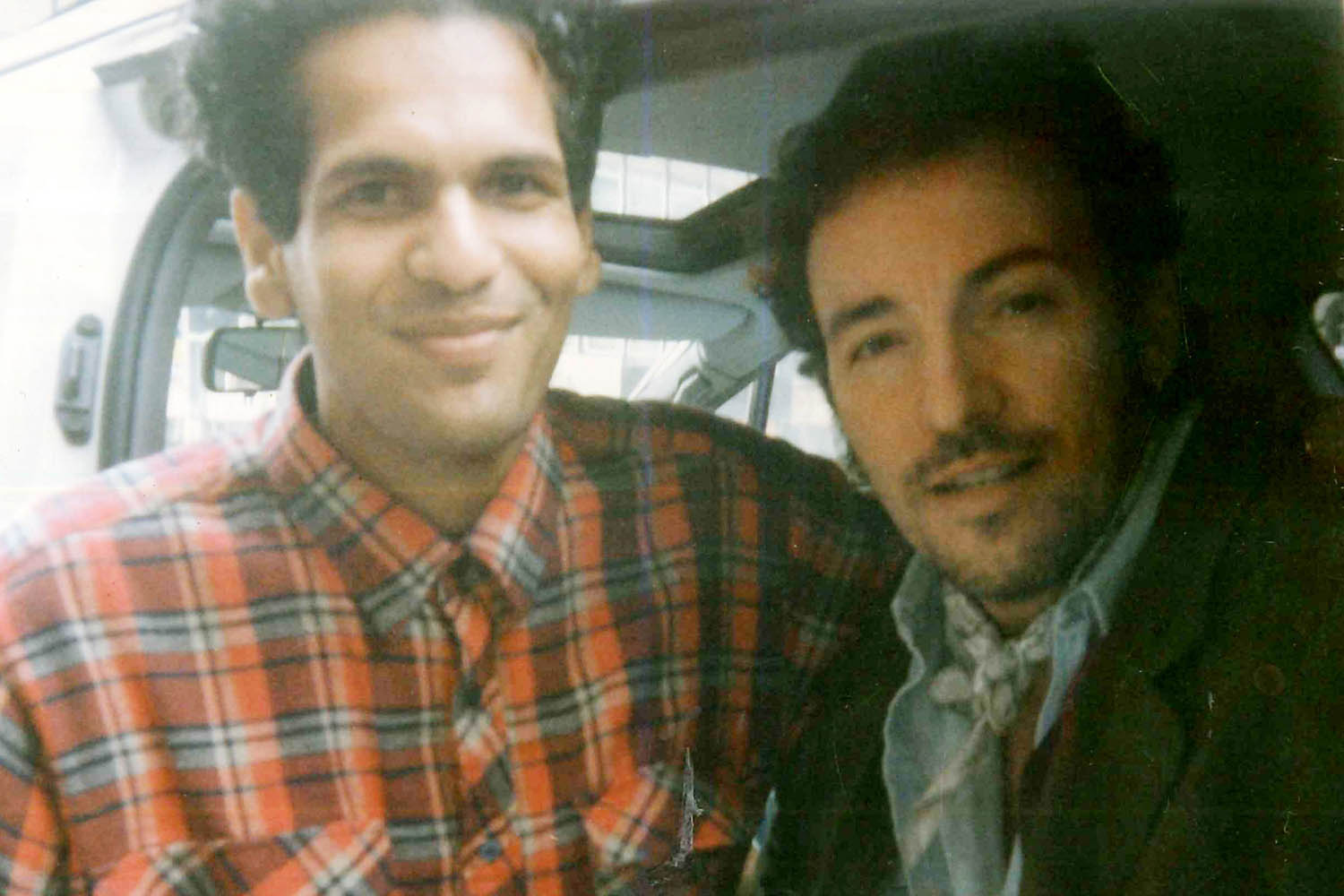

Sarfraz Manzoor with Bruce Springsteen 1993

“No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear,” writes CS Lewis in A Grief Observed, his account of the aftermath of the death of his wife. When my father died I was at an age where one is meant to believe the world feels open, but my own world felt as though it had compressed into a tight ball of pain and uncertainty. I did not have a job and lacked any direction. The death of my father left me aware that if I was going to make anything of my life, I would have to do so on my own. That fear hardened into an urgency, the urgency that comes from knowing you are walking through life without a safety net.

Scene two takes place in London, in 2003.

At the time of my father’s death I had been doing unpaid work experience at Granada TV. The urgency sharpened my ambition. The following year, I secured a much-prized traineeship with ITN. Jobs at Channel 4 and the Guardian followed. In July 2003, I received an email from a literary agency asking if I was interested in writing a book. I met the agent and told her that the book I was most interested in writing was one about the two men who had, I realised, most shaped my life – Bruce Springsteen and my father. When I first imagined writing Greetings from Bury Park, I thought I was writing a somewhat lighthearted and improbable story about the impact of an unlikely musical hero. It was only when I started writing it that I realised that the book was actually the work of someone working through trauma. When I reread it recently for the audio edition, I found parts of it almost too painful to read out loud. The book was, I realised, my attempt to start, and continue, a conversation with my father that had been brutally cut short a decade earlier.

Scene three starts in Hay-on-Wye, in 2017.

Related articles:

It is the last weekend in May. The phone rings. It is the film director Gurinder Chadha. She never calls me so I know it must be important. It is.

It had been 10 years since the publication of my memoir, and seven since I had started working with Gurinder on the script for a feature-film adaptation of it. The second writing journey had often been deeply emotional because, in recreating my teenage years, I had once again had to spend time thinking about my parents not only as parents but as people. I was grateful that it again gave me the opportunity to continue that conversation with my father that had begun in the book. Still, if I wanted the film to actually go into production, there was one person whose approval was pivotal. That person was Bruce Springsteen.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The story in the film focused on only a small portion of my life – from 16 to 18 – and the role that discovering the music of Springsteen played in transforming my life. The film needed his music and the only person who could approve that was the man himself. I had two things going for me: I knew Springsteen had read and liked the book because he had told me so at an event back in 2010; and I had Gurinder Chadha on my side. Gurinder had asked me to write an email directly to Springsteen. I poured everything into that email, explaining how the story was not only mine but that of my parents. The email was sent and we heard nothing for two weeks until the phone call from Gurinder on the last weekend of May 2017.

She told me that she had heard from Springsteen’s people that Bruce had read the script and he had a response. “What is the response?” I asked. “He says he’s all good with it,” she replied. “What does that mean?” I asked. “It means we are making a movie.” Gurinder said.

Viveik Kalra in Blinded by the Light (2019)

Blinded By the Light started filming the following spring. It was billed as being about a teenage boy’s obsession with Bruce Springsteen, but for me the film was really always about my relationship with my father. Javed, the name of the teenager in the film, was the name I was given before my parents decided on Sarfraz, and Javed’s father is called Malik, an Urdu word that can loosely be translated as boss. I remember being on set and spotting Kulvinder Ghir, who played Malik, for the first time. He looked and was dressed uncannily like my late father. It was so emotional that I steered clear of him while he was filming. I could not look at him at all. My father’s death is not depicted in the film, which ends with my leaving for Manchester, but it is the part of the iceberg that lies beneath the story on the screen.

Sarfraz Manzoor photographed at home in London

I remember being in a cafe working on the script and trying to imagine what my late father would say if he was still around. A line came to me and I remember typing it and immediately breaking down in tears. The line appears towards the end of the film when the father says to the son: “Tell your stories but don’t forget ours.”

Scene four starts in London, in 2025.

It is mid-January. The phone rings. It is my brother calling. He never calls so it must be serious. It is. My mother’s condition has worsened and she is being taken to hospital. I need to come immediately.

It was a phone call I had long feared but also long expected. My mother, Rasool Bibi Manzoor, had suffered from Alzheimer’s for a number of years and even before the more recent terrifying symptom of refusing food, we had noticed the remorseless erosion of her memory. When I would visit she would, mostly, be all smiles but I knew better than to ask if she knew who I was. There was a painful irony to the fact that even as I sought in my work to preserve my family’s stories, my mother was forgetting them. I returned to Luton and, for the next three weeks, my siblings and I sat at her bedside in hospital, and later at home, where she died in the afternoon on the first Monday in February. She was buried, following Muslim tradition, the next day.

Kulvinder Ghir looked uncannily like my late father. I steered clear of him during filming

Kulvinder Ghir looked uncannily like my late father. I steered clear of him during filming

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” writes Joan Didion at the start of The White Album. Next weekend, the last of May 2025, is the 30th anniversary of my father’s heart attack. That same weekend, the BBC is, by coincidence, showing Blinded By the Light. The world depicted in that film is long gone, those turbulent teenage years are decades in the past. My parents are both dead but they are not gone. We tell stories in order to live but also in order for the dead to live again. I am looking at my parents even as I type these words. My father is dressed in a white shirt with pale stripes and he is wearing a tie, even though it is a warm day. My mother is wearing a pale brown shalwar kameez with a dupatta draped around her neck. She is smiling warmly. When I look at her photograph, framed and on my desk next to the one of my father, I feel strangely reassured she is not really gone. I look at them both, and when I move closer to their paper faces, I swear I can hear them speaking to me: “Tell your stories,” they whisper, “but don’t forget ours.”

Blinded By the Light is showing as part of a Bruce Springsteen-themed night on BBC Two on Saturday 31 May. Sarfraz Manzoor is on Bluesky @sarfrazmanzoor.bsky.social

Photographs courtesy of Sarfraz Manzoor, Warner Bros, Antonio Olmos/Observer