Photographs Chiara Goia

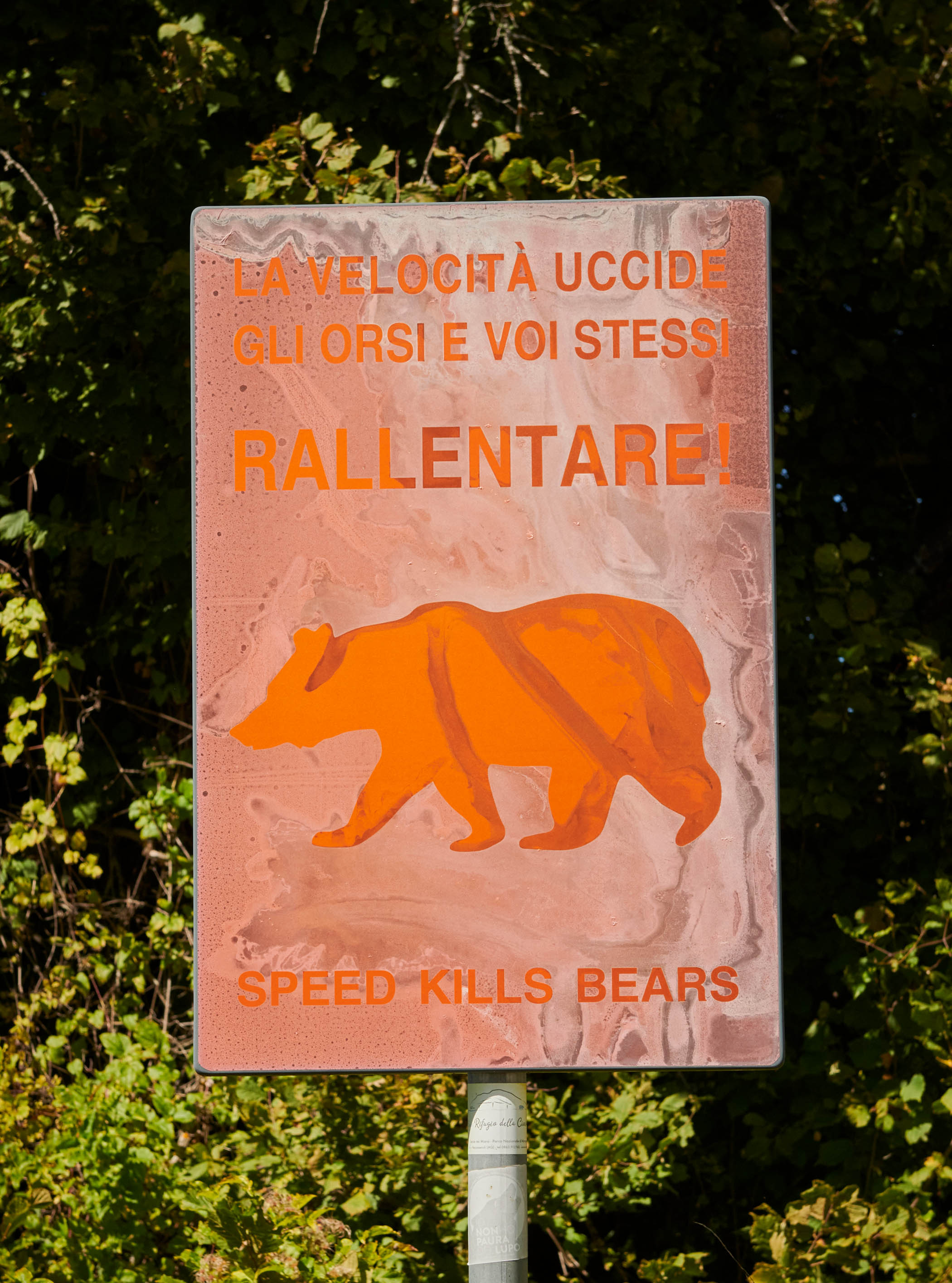

We slow down at a short run of houses and, before the next bend in the road, take a right at a church far too big for this whisper of a hamlet on a mountain pass. We park up behind Gioia Vecchio’s church, by a row of green metal bins. There’s a picture of a bear on each, and a sign saying “Close lid tightly”. A fed bear, as they say here, is a dead bear.

I am here on a five-day group trip to hike in the unsung Apennine mountains, said to be the most spectacular in Italy after the Alps, and to spot the wolves and bears that coexist with humans here in the Abruzzo National Park. Our base is the nearby town of Pescasseroli, at the heart of the park.

It is a Sunday evening in September, and a dozen amateur wildlife enthusiasts are lined up against a wooden railing, the spectacular Marsican mountains all around, the valley floor stretching out below. I take my place at this popular observation point beside a man with a whopper scope on a tripod. Nice kit, I think, eyeing up his thermal imager, binoculars and natty padded jacket. I pull out my weedy binoculars and, copying everyone else, scan to the right, over the mountain ridges, down to the woodland and the valley floor, then repeat. The plan is, “glass” the landscape like a pro, channel some David Attenborough animal magnetism and, come twilight, yours truly will be the first to whisper, “Bear, valley floor, two o’clock!”

It won’t be easy, though. I’m rubbish with binoculars, the Marsican bear (a subspecies of the Eurasian brown bear) is shy, and in the 4,000 years it has lived in the region, the Apennine wolf has learned to avoid humans, aided by a patchwork coat of tawny, red, grey and brown, camo befitting an apex predator once hunted almost to extinction. Today, there are around 3,300 of these wolves in Italy, with about 40-50 of them living in Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park. But, as our Coexistence Adventures guide Francesco Romito tells me, “They are like ghosts. If they don’t want to be seen, they won’t be.”

In the event, we leave Gioia Vecchio, having watched elegant roe deer up on the mountain ridge and a slow, show-off sunset. My group seems happy with that, judging by the excited chat over dinner in our family-run hotel in Pescasseroli, and I’m happy with the whole group shtick. It doesn’t seem to matter that we don’t know each other – a shared interest in wildlife swerves painful small talk. This lot do know their onions, though: one woman designs digital tracking collars, another protects jaguars in the wetlands of Brazil’s Pantanal, and there’s a bedpost notcher-upper (of wild animals, not sexual conquests) who’s seen every trophy animal going, many times over. Bottles of organic Pecorino Terre di Chieti ease the bonding as we tuck into steaming bowls of pasta e fagioli.

It’s a different kettle of fish at 5.30am the next morning, a time at which I cannot bond, a time at which I find myself in a minibus heading for a dawn wolf-spotting excursion. Everyone is chatting – it’s like a crepuscular mobile cocktail party, without the liquor. I rest my head on the window and emit negative energy, like a lone deer deflecting a hungry wolf. Happily our guide, Umberto Esposito, recommends silence as we sit on the side of a steep hill. The cows didn’t get the memo, though: they moo nonstop, somewhere in the valley. But it’s peaceful all the same, the possibility of glimpsing this mythologised and demonised creature seeing off any sense of impatience. I tune in to the sounds and colours of the meadow and mountains, quite forgetting the cold. I unfurl with the changing light.

I nearly cartoon-tumble down the hill when time is called on our morning watch two hours later. I lunge at a shrub as I clamber to my feet. Back at the hotel, I reward myself with four different kinds of cake (the chestnut gets my vote), and then explore Pescasseroli. It’s quietly charming. A hub for winter sports and a starting point for biking and hiking trails, mountains edge the town. Wrought-iron balconies drip with bright flowers and laundry, and there are several unshouty but very good regional restaurants (the tagliolini porcini e carpaccio di tartufo at Ristorante Luci is mouthwatering). A lady sits in front of her house, painted bears on the wall behind her. Men play cards outside the tabacchi.

After coffee and a pistachio ice-cream at Bar dell’Orso (Orso meaning bear) on Piazza Vitorio Emanuele, I chance on a chic boutique selling the perfect cashmere cardigan, and narrow streets off Via della Piazza lined with grand houses. There’s even a small palace, now a museum. It turns out that people make the two-hour drive from Rome to Pescasseroli on weekends. Many have second homes here. That explains the cashmere.

We hike every day, each walk upstaging the last, dense forest giving way to plateaux of grazing horses, hoof fungus growing on giant tree trunks, lilac cyclamen brightening the forest floor. “It’s like a magical Tolkien forest,” says a member of the group as we wind our way through a 500-year-old beech forest, a designated Unesco world heritage site, in the Valle Cervara. “Look at their shapes and sizes, how huge they are,” Umberto says, pointing to the monumental trunks which attract insects, mushrooms and woodpeckers.

The sun is pushing through the canopy of a new-growth beech forest the next day as we head up to Mount Meta, home to chamois. When I was a child, friends’ dads used to hold up squares of yellow cloth before performatively cleaning their cars – no mention of the curly-horned ungulates that produced the cleaning cloths. Now I want to see chamois undulating about on their rocky perches. In the event, we spend too long lying on our backs after a picnic lunch, counting griffon vultures and watching rutting stags, and don’t have time to reach the summit. On the descent, I walk behind the group’s conversational livewire, who is armed with Nordic poles. She got her dodgy ankles, she volunteers, on account of climbing up a ladder into the mouth of a giant sculpture by Anish Kapoor at Versailles. “What shape was it?” I ask. “Horned,” she says, “and bright red. The locals called it the queen’s vagina,” out of which she then shot “like a cannonball.”

By the time we go canoeing on Lago di Barrea, a beautiful manmade lake below the medieval hill town of Villetta Barrea, I am resigned to not seeing wolves or bears. The bonding continues apace, even when m y canoeing partner and I get stuck in a side channel of willows and poplars. I admire their trunks growing in the water, to which he replies that wolves love a riparian forest – so now I know the word “riparian”, which I shall use whenever I can.

That evening, minutes after we’ve lined up against the railing at Gioia Vecchio, a much more thrilling word travels up and down the row: “Orso! Orso!” A solo Marsican bear is crossing the meadow, muzzle down, its gait at once purposeful and delicate. Whoop-whoop goes my awestruck heart at seeing this endangered species walking, seemingly unafraid, in its natural habitat. Now I know what awestruck feels like.

The next morning, on another dawn recce, three juvenile wolves appear. I’m the last one to find them in my binoculars, obviously, and I lose them when they walk near rocks or bushes, but then two of them play with a plastic bottle in plain sight. I am enchanted all over again. Local farmers, by contrast, would be spitting blood. For them, coexistence with wolves is a luxury many can ill afford.

As a national park, Abruzzo is unusual because, unlike Yosemite, for example, humans live here, too – and, like the Apennine wolf, always have. Today their coexistence is a political hot potato. There are very few traditional shepherds left, leaving sheep, along with dogs, deer and other livestock, vulnerable to wolf attacks if fencing is absent. Some farmers seek EU compensation for killed livestock, even when wolves are not the proven culprit. For them, the downgrading by the EU earlier this year of the wolf’s status under the Bern Convention from “strictly protected” to “protected”, which allows for culling, is welcome. Not so for local conservationists.

Their biodiversity initiatives and creation of wildlife corridors that protect both wildlife and humans is further thwarted by private companies acquiring grazing land without bringing grazers to market and claiming EU agricultural subsidies. “It is a pity to talk about this,” says Umberto, “but this is Italy, and there are big organisations that are working on this new method of gaining money.” The mafia is moving with the times.

For details of Coexistence Adventures in 2026, see theeuropeannaturetrust.com

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy