A confession: the Henry Moore Institute is my idea of art-world integrity. It has a remit so tough most museums would have dropped it long ago. Rooted in the ambition of Henry Moore, founder and first patron, to promote sculpture to the widest possible audience, it somehow manages to unite novel research with traditional art history, to fund wild projects and mount some of the most original exhibitions anywhere – all while keeping Moore’s principles (and very often his sculptures) in view.

The Henry Moore Institute has shown ancient Greek statues, depilated Victorian nudes and outlandish scholar’s rocks from 17th-century China. It has invited us to think about sculpture in terms of time, movement, colour and scale, not to mention electricity and humour. It has shown ideal portraits and living monuments, inflatable forms and prosthetics, sculptures made of words, sealing wax or string. And just about any contemporary sculptor to whom a large survey is devoted at some grand institution was shown first in this smaller one (this year, Do Ho Suh at Tate Modern).

Now the institute presents the first major sculpture exhibition in Britain created by blind and partially blind artists and curators. Beyond the Visual is an immediate challenge to the senses. This is not just because some of these works take their power from sound – Aaron McPeake’s sonorous brass hoops, say, or the rainy patter of Jennifer Justice’s wooden droplets on brass chains. Nor because some of them have a particular scent, redolent of marshy landscape or industrial welding. Nor even because one of them is quite literally barely visible – an object inside an opaque vitrine that can only be experienced, or revealed, so to speak, through the words that describe it on an audio loop.

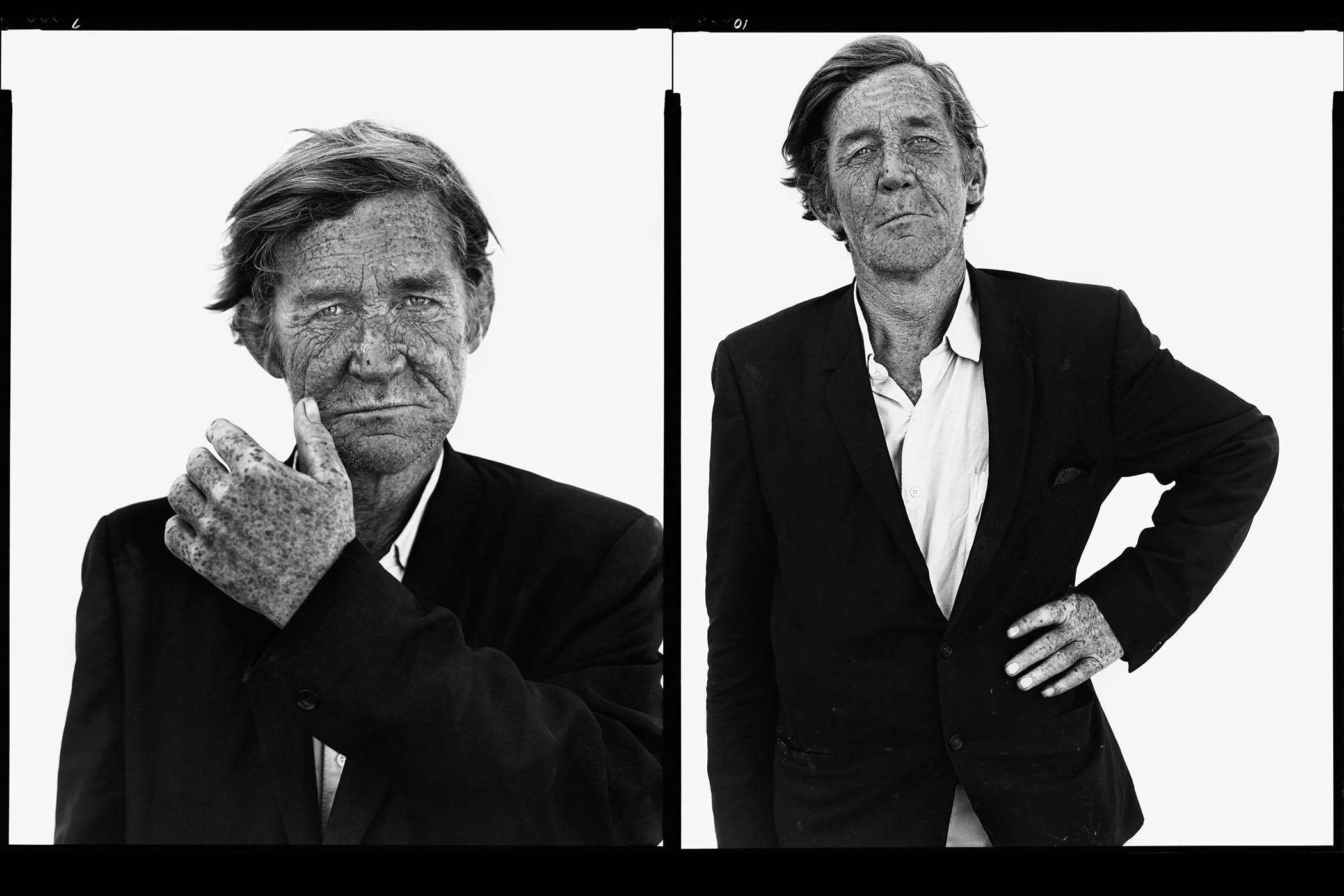

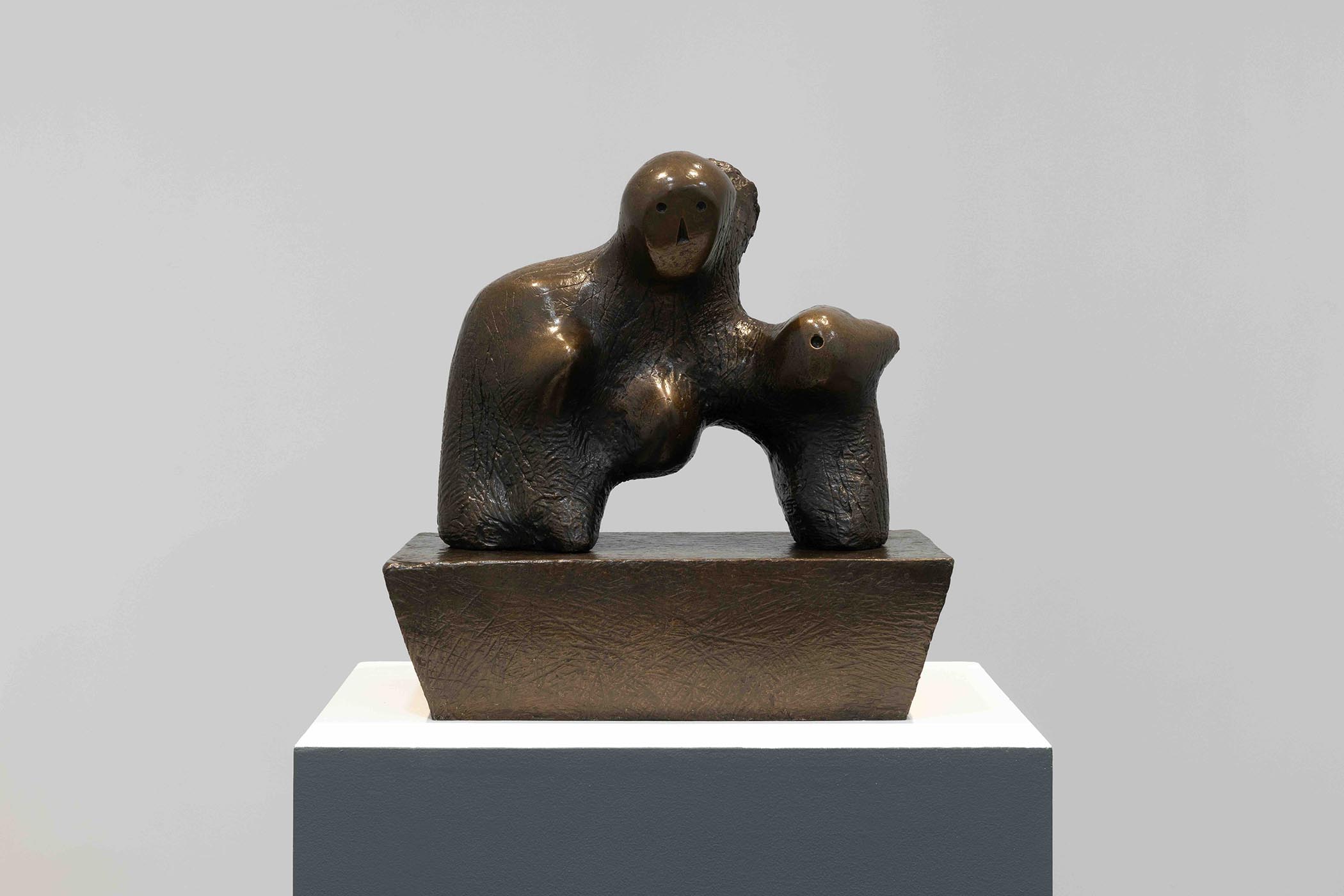

It is rather that the sight of these artworks is far from their only outstanding attribute or quality. That might have been true of some of them all along, specifically the tabletop bronze by Henry Moore that turns out to have a ringing echo when knocked and a chill beneath the fingers.

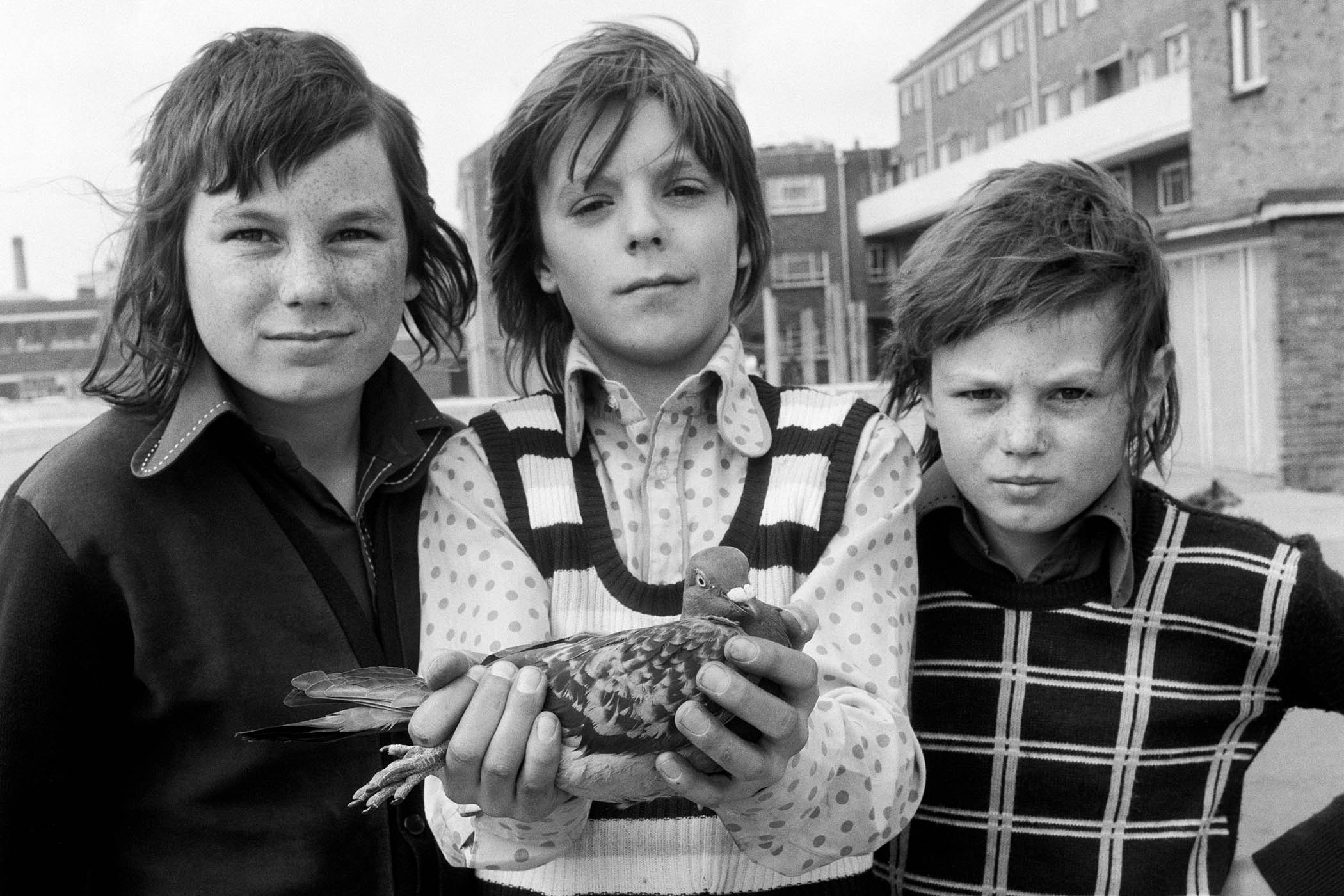

Henry Moore’s tabletop bronze turns out to have a ‘ringing echo when knocked’. Main image: Aaron McPeake’s sonorous brass hoops

Moore’s bronze sculpture has ‘a chill beneath the fingers’

Its tactile properties are peculiarly null, for a sculpture, compared to the wonderful abstractions in white plaster laid out on tables in another gallery. Lenka Clayton’s Sculpture for the Blind, by the Blind, made in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, is a riveting experience. You run your hands over these ovaloid objects and feel nameless events in the weight and surface and shape. Some seem to have edges, or unexpected dips, or to culminate in anatomical protrusions; others seem lonely or mysterious. None of these sensations could be predicted, perhaps even perceived, by the eye.

Visitors are invited to touch everything in this show: the spinning washer on its taut wire, the panels of rusting, welded metal that invoke the volcanic landscapes of Iceland, pitted with sudden holes and emitting an eerie resonance when brushed by the fingertips. The Barry Flanagan elephant from 1981, as good a representation of this gentle herbivore as any I have seen.

The strength of its legs; the papery flatness of its ears; the curious balancing act of trunk and tail: all of these became newly evident through touch. And all are described, and analysed, by the blind writer Joseph Rizzo Naudi, in a narration on headphones that exceeds the wall texts of most museums in its figurative eloquence.

A programme of films is screening downstairs, all carefully voiced, including an extract from Pete Middleton and James Spinney’s intensely moving 2016 documentary Notes on Blindness, with its incomparable portrait of the theologian John Hull whose gradual sight loss eventually became the source of his philosophical masterpiece, Touching the Rock. One senses Hull’s significance for other artists in the show, including the Canadian Collin van Uchelen. His glowing wall panels translate starbursts and pyrotechnic fireworks into brilliant lights, but also into linear indentations in the surface. The travelling touch through these vectors – across sharpened ridges, through conjunctions, to abrupt conclusions – has an explosive force that the constant LED colour somehow cannot achieve.

Related articles:

‘A riveting experience’: You run your hands over Lenka Clayton’s Sculpture for the Blind, by the Blind

There are other revelations for all. A table with four chairs appears humdrum enough, but run your fingers under the tabletop and you feel something: a sequence of tiny lumps evocative of the last sitter’s chewing gum. This substance is resinous, however, still mobile and alive. It is a sharp new experience for any visitor; the ordinary becoming, through sculpture and hypersensitivity, super-real.

In one room, you are invited to reach through circular holes and rummage inside boxes of hidden objects. A toy cockerel turns out to be a dog, when I withdraw it; I can only identify some cellophane by sound. How ignorant are my hands. A polished marble egg, not incidentally, now seems amazingly dull compared to all the sculptures in this show; such is the banality of expensive facsimile.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The marvellous marble “windows” of the Dutch sculptor Lucia Beijlsmit, by contrast, conjure castle battlements, cathedral windows, church arches and all kinds of rocky outcrops. But they also dramatise more abstract distinctions, between slow sheen and quick polish, between gouge and incision, crag and plane. And all of this is made as apparent to the hand as to the eye.

It is this expansion of what sculpture – and exhibitions – can offer to the senses that makes this visit so special. Beyond the Visual actively alters one’s experience of art, taking it beyond the dominance of sight. All are welcome, all can touch, all are equal. Another small revolution for the Henry Moore Institute.

Beyond the Visual is at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds; until 19 April

Photographs by Joanne Crawford/Rob Harris