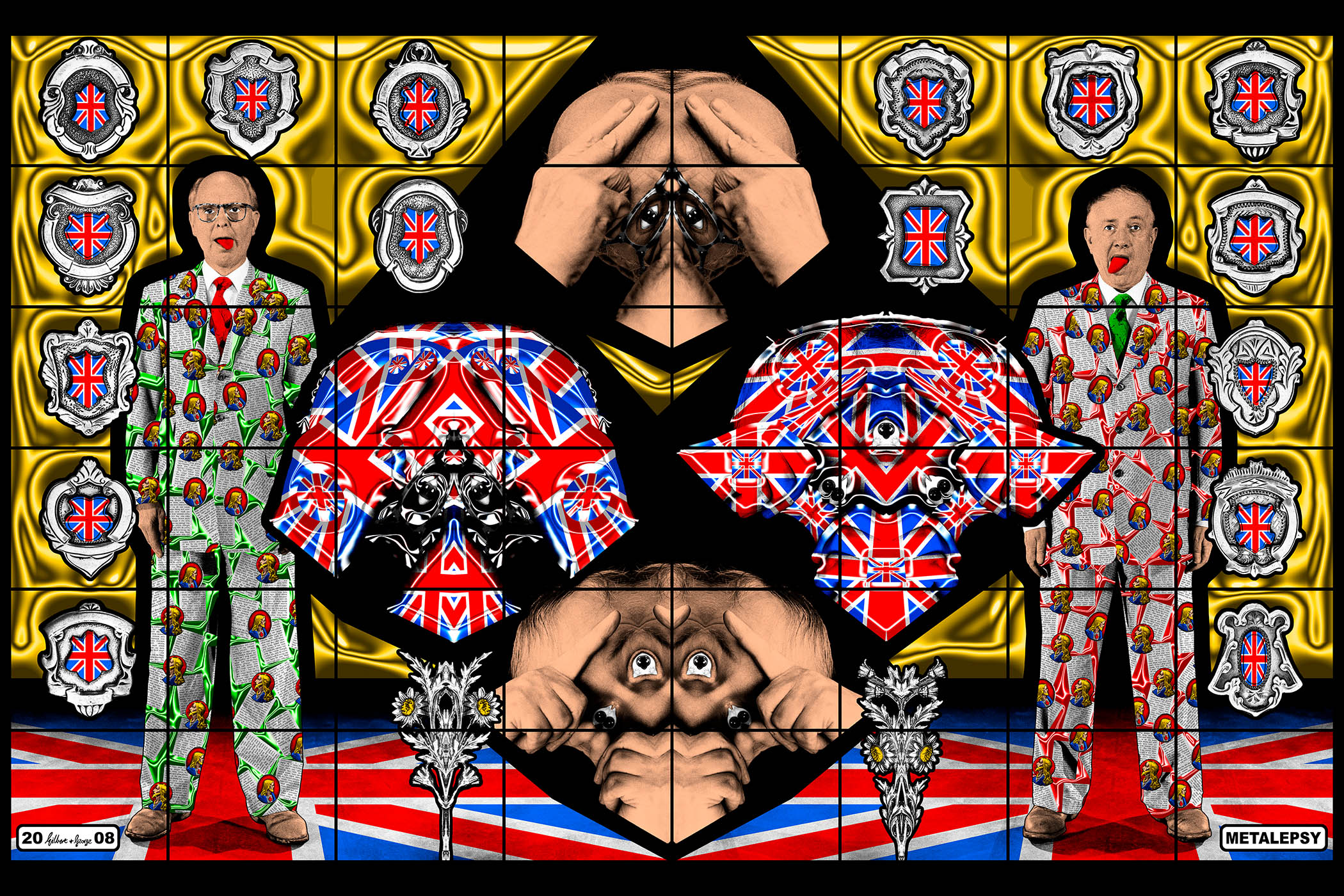

Raucous, gargantuan and gleefully null: what’s new in the art of Gilbert & George? The century passes with barely a shift. The Hayward Gallery’s 25-year tribute, 21st Century Pictures, presents more than 60 works the size of cathedral windows in the usual hyper-saturated hues, from the red, white and blue of the duo’s rightwing royalism to a newly lurid magenta, cyan and lime. Come on in, warm your hands on all this brightness: that’s what the colours say, winking as you notice the same old black and white grime behind them.

This is G&G’s eternal East End as monochrome backdrop: friable bricks and dusty graveyards, chained gates, graffiti and discarded nos canisters. The lexicon of London is picked out in red tabloid nouns: victim, murder, verdict, gangs! The artists’ supposed themes are spelled out in so many (or so few) words. Money, Sex, Religion, Homo, Muslim, Fucking, Queen, with the endless reproduction of what used to be phone-box ads throughout. At least the times are changing here – personal services available on mobile numbers now, as well as 0171 landlines.

Gilbert & George are always present, indivisible from their art and vice versa. Only imagine how meaningless these colossal images would be without the everyman duo in their matching suits. Voguing, mooning, mugging, leering, hands pressed to faces in mock horror, they appear increasingly vaudeville, pretending to be pensive, pious or shocked. Sleep Over has them in crimson, playing dead on a bed of bones. Slugged shows them laid low by a pair of outsize slugs. They are not above humdrum puns.

The format never alters and is, by now, the most forceful aspect of their art: eye-popping colour against monochrome grit, word against image, all the urban sound and fury contained in a tidy black grid. Remove these grids and the art would falter. They keep everything in order, separating hoardings, tags and headlines that would be otherwise indiscriminate, mimicking stained glass leading, as well as gunsight crosshairs; giving graphic zip and register to wilfully ambiguous content.

Fates, a work from 2005, shows G&G flicking the Vs in perfect symmetry. There are ginkgo leaves, hands bearing stigmata, nods at mosque architecture and a couple of Asian lads. The title is spelled out in faux-Arabic script. The artists, as usual, are working both sides of the street, Christian to Islamic. But saying what, meaning what, gesturing at whom? The grids give specious coherence.

I strongly doubt that many Tommy Robinsons will drift in, for all the kitsch patriotism of London buses and ERII stamps

I strongly doubt that many Tommy Robinsons will drift in, for all the kitsch patriotism of London buses and ERII stamps

Of course theirs is a practised neutrality, much vaunted in interviews. Gilbert & George are just free-floating spirits, observers, occasionally spectres, hovering in ghostly grey patches. The digital technology they have used since 2003 allows them to appear babyish, to morph into hominids, spacemen or weird twins, like those little devils sniggering in the margins of medieval manuscripts. It is not just that they never pass judgment, or that they mock all religions as equally superstitious (what a novel idea), but that every motif appears prophylactically sealed behind glass. These grids allow the artists to watch, and depict, the world as if seen through the panes of a window. And that has now become the worst aspect of their work.

Here are homeless people having a can, a fag, a laugh, driven nuts by drugs, piece by neat piece. Here’s Marley Walk, where the sky is raining weed bags emblazoned with Bob’s face (get it?). The artists look up with dismay. In Fournier Street, where they live, townhouses have now exceeded £5m. Passengers pass by on double-deckers, seen only in profile. Graffiti materialises anonymously. The people in the streets are nameless.

“Art for All” is what G&G always claim they’ve been making for the past 50 years and more, apparently unaware that this show is neither free (£20 a head) nor as democratic as they hope. I strongly doubt that many Tommy Robinsons will drift in, for all the kitsch patriotism of London buses, red phone boxes and silver ERII stamps.

It has, of course, been judiciously curated. You will not see Date Rape (with its terrible dried-fruit gag), or Paki (sic), or indeed any work that relates to Ukraine or Gaza, Putin, Netanyahu or Trump, Rochdale rape gangs, trans activism, immigration or surging Reform. Their fence-sitting is beginning to look less contrarian than timid. And by the time you get to the end of this Imax-scale performance, which lacks variation in tension or pace, the visual kick has faded to numbness. The art is in your face, as always with Gilbert & George, but it never gets as far as your heart or head.

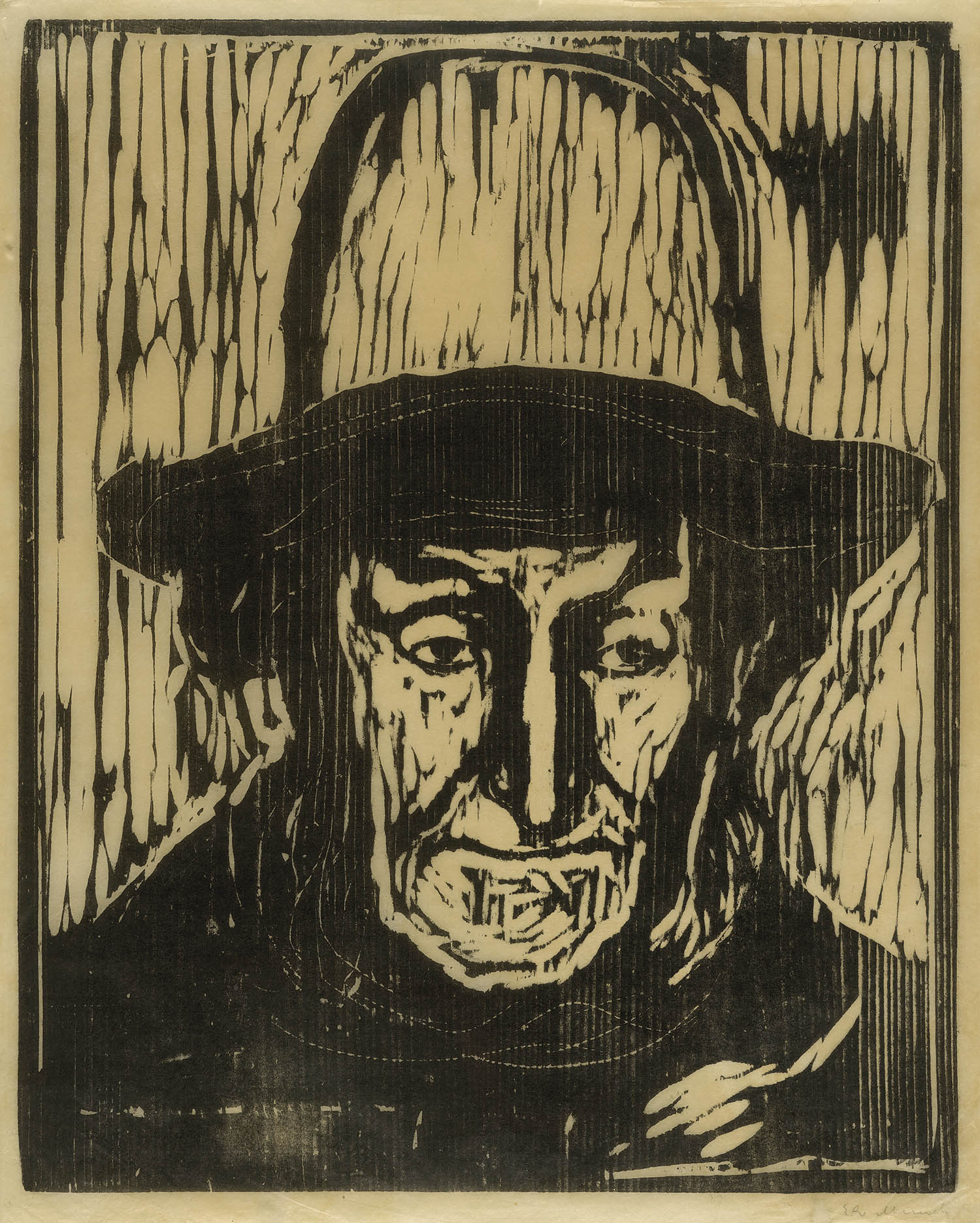

‘Inky darkness’: Munch’s The Old Fisherman, 1897.

For the distinctive clarity of graphic art, go to Nordic Noir at the British Museum. All that unites the 150 and more works on show is that they were made on paper. Munch’s woodcut of a melancholy loner picks him out of inky darkness in a pale glimmer. Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s coloured-pencil firs turn into flying birds or disappear, frame by frame, into the snows of the white page. A screenprint by the Sami artist Britta Marakatt-Labba shows crows transforming into policemen marching upon tents in turn filled with her people. Authority vanishes into ice.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Swedish fishermen, Finnish reindeer, a superb drawing of a lunar eclipse above the Arctic Circle by Norwegian artist Rina Charlott Lindgren: Scandinavia materialises in all its remoteness through aquatint, etching, monoprint and lithograph. There are famous names – Mamma Andersson, Jockum Nordström – and startling discoveries, such as the still and silent landscape art of Finland’s Lea Ignatius. Most stupendous of all is Ragnar Kjartansson’s burst of red and yellow flame, tearing up an outsize print as rapidly as a struck match, a blaze of firewood made entirely out of wood.

Gilbert &George: 21st Century Pictures is at Hayward Gallery, London, until 11 January 2026. Nordic Noir is at British Museum, London WC1, until 22 March 2026

Photographs courtesy of White Cube/Trustees of the British Museum