‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

Emily Dickinson

Hope is a bird. It never stays still. It darts about inside the human soul like a lark in the sky, surging upwards without explanation, singing songs without knowing any words, sustained only by its own uplifting wings.

A bird is also a form of magic. Birds have the power to leave our world at will. They appear, and vanish, so mysteriously that our language has no words left for their unparalleled motions – swooping and diving, circling and drifting, pecking, hopping, fluttering, twitching, soaring and disappearing into the blue. How to keep this nonstop creature still; how to draw a bird, when stillness is against its nature?

The easiest way, alas, is simply to kill it. This is the mode of still life, or nature morte as art history morbidly calls it. Seventeenth-century Dutch art, with its infinite sub-specialisations in every genre, has many masters of the stone-dead bird, laid out on a ledge with flowers or fruit or other once-vital creatures. Jan Weenix found fame with the most exotic birds he could acquire, shot by hunters outside his native Amsterdam. He started out with cockerel, guinea fowl and partridge, moved on to brilliant turquoise kingfishers, positioned for eye-catching effect in the foreground of these pile-ups of avian corpses, but is most renowned for his paintings of dead swans.

Carel Fabritius’s The Goldfinch, from 1654. Main image: a watercolour of a blue European roller’s wing by Albrecht Dürer

Weenix painted many swans, each commission a boast for its wealthy owner, for it was a restricted privilege to be allowed to hunt these large birds. Nobody quite knows when the Mauritshuis museum’s masterpiece was painted, though Weenix was likely in his late 60s or 70s. Decades of study are condensed in this vision of the spreadeagled swan: the shine on its immense articulated wing, the opalescent whiteness of the breast, running from pearl to gold, the soft underside of the tail. Weenix paints what we could never see: not just the breast but the legs that keep the water ballet afloat. For this noble bird is hung up by one foot, in order to display its majesty at full length. The neck becomes a limb, gracefully descending towards the cruel butt of a gun. Weenix adds a smaller corpse for scale, a finch the length of the swan’s beak. The sight is frightful, unnatural: a stately bird rifled. The finch is given more dignity.

Yet this is also a painting of awestruck knowledge. Because what are they, these creatures, two-limbed like us and yet nothing like us at all? Diogenes is said to have mocked Plato’s definition of man as a featherless biped by turning up with a plucked chicken: “Here is Plato’s man.” For many artists, the difference is so obviously the miracle of flight that the wings become paramount. Leonardo scrutinises the anatomy of bone and ligature in his drawings to try to understand the mechanism of bird flight. Dürer’s watercolour of the rainbow glory of a blue European roller’s wing is equal, in all its astoundingly beautiful particularity, to the serried pennants of the wing itself.

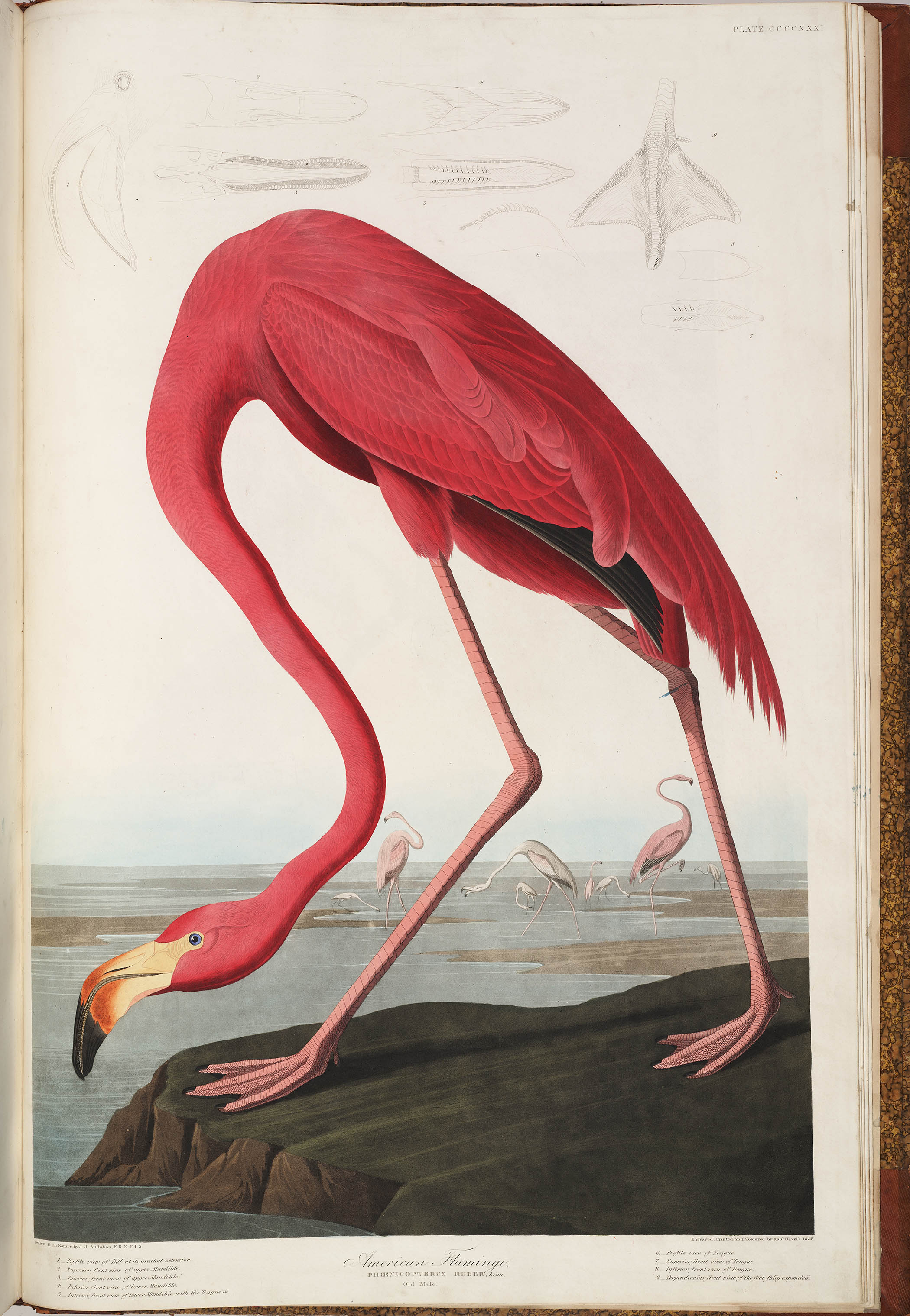

These birds are by definition dead, their wings laid out, their legs examined for backward-moving joints. The American birdman John James Audubon went so far as to kill and eat most of the thousands of species he painted, from bald eagles to snowy owls and even that preternaturally still bird, the heron, while travelling the continent with gun and brush. His American flamingo, from The Birds of America, is an adult male spotted as Audubon passed through the Florida Keys. He captures something of its bizarre anatomy but the bird is subjugated to the design; perfect for what would become Audubon’s most popular poster.

John James Audubon’s engraving of an American flamingo

There is a staggering photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson of a bird keeping still for an artist. The elderly Matisse holds a white dove in his one hand, while sketching it with the other. The bird does not seem to flinch. Three more doves sit on top of a cage, unconfined, as sunlight streams through the studio window. Matisse, quick as a bird, will soon return this dove to its freedom.

Matisse allowed birds to fly all around his house in the south of France. They flitter through his later cutouts. His studio assistant recalled that it was the shape of a bird that first inspired this innovation: “Matisse had cut out a swallow from a sheet of writing paper and, as it distressed him to tear up this beautiful shape and throw it away, he put it up on this wall … Over the following weeks other shapes were cut out and put up.”

Matisse gave his last doves to his old rival Picasso: “They look like some you have already painted.” A white dove became Picasso’s symbol for the 1949 Paris World Peace Congress. You might say it became his own emblem. But that dove, like so many birds in art, is a flight of fantasy – or a feat of memory. For though cameras can now catch the millisecond beat of a hummingbird’s wings, almost everything drawn or painted or sculpted must originate with a recollection.

It is true that some birds can sit still all day, especially birds of prey. A peregrine spent most of one winter waiting motionless on the top of Tate Modern. In Hyde Park, a tawny owl once sat so long in a tree that birdwatchers from all over Britain could depend on seeing it. With their flat faces and human-seeming gaze, owls are more readily portrayed than other birds.

Matisse holds a white dove in his one hand, while sketching it with the other. The bird does not seem to flinch

Matisse holds a white dove in his one hand, while sketching it with the other. The bird does not seem to flinch

Still, the nameless artist who descended beneath the earth, through narrow airless passages and terrifying darkness to the Chauvet cave in the Ardèche had to carry an image of an owl in his head in order to scratch it into the wall. Ornithologists have identified it as an eagle owl, the largest and fiercest in Europe. Made more than 30,000 years ago, it is thought to be the oldest image of a bird.

Only the most intrepid caver could reach it, even then, and now the Chauvet cave has been sealed up for public safety. Why is it hidden down there? To come across it, flashing up by the light of a flame in blackness, must have been an astonishing revelation.

The bird is a mythical messenger (think of angels) or an augury of the future (birds’ entrails). Egyptian gods have the head of a bird, bulls and dragons are winged. Western art depicts the Holy Ghost as a dove hovering above a sacred figure in a blaze of white light: the bird as UFO.

A bird is the spirit of light in itself, of energy, prospect and vitality. It tells us the time – cock crow and starling murmuration – and forecasts the weather. Swallows fly high when it is dry, low when rain is coming; seagulls wing their way inland when a storm is impending at sea. The flight of geese over ancient Egypt announced the shifting of the seasons, just as their sorrowful departure for warmer climes heralds winter in Europe. In art, they may be a warning. Those black crows flying up from the cornfield in Van Gogh’s late painting, as if scattered by the crack of a gun, seem to sense the fatal future.

Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows depicts the birds as if scattered by the crack of a gun

The beauty of birds is scarcely the only reason we have to depict them, or we would not have paintings of shoebills or humdrum sparrows. Birds invite an attentiveness beyond other creatures; they can be heard even when you cannot see them. In Hokusai’s wondrous Bullfinch and Weeping Cherry-Tree, there is no sense of up or down and the eponymous bird is barely visible at first. So giddy is the sense of floating among bright petals, the bird no help with optical orientation, this print is sometimes displayed the wrong way up. Our eyes, like the bird, are lost in nature.

Art may aspire to be bird-like – delicate, airborne – and yet remain earthbound. Forever young, forever strange, no matter that we cage or tame them, birds may inspire works of art without ever quite – or entirely – alighting inside them. It is not just that early painters often worked with corpses or stuffed skins, with no sense of how their subjects moved or behaved in reality. Nor is it that poetry carries the dematerialising spirit of birds so well, from Shelley’s joyous skylark to Dickinson’s darting soul of hope. It is that art must keep a bird captive in order to capture its essence.

And perhaps that is why The Goldfinch of Carel Fabritius rises so high above other images, so to speak, in its peerless portrait of the little bird on its perch, so abrupt and austere, one eye glistening as it turns its head out of profile towards you, face to face in this sudden moment of noticing each other across time and space. Fabritius stills the goldfinch twice: once by showing it imprisoned by the chain around its leg, so that it can never fly away. And again within the frame, for it can never escape this painting. The beauty of Fabritius’s masterpiece is in exact tension with its poignancy: the enigmatic bird, so gentle and solitary, with its flash of golden wing, its alert eye and yearning body, perhaps still full of hope, held here before you as a fellow being, captive, no longer on the wing. It is the greatest painting of a bird in all art.

Birds is at the Mauritshuis, The Hague, until 7 June

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Images by Alamy, Mauritshuis, The Hague and Historical Picture Archive/Alamy