French flags freeze in mid-flutter against a high summer sky. Pale clouds hang motionless above the glassy surface of a sun-struck harbour. In Georges Seurat’s Sunday at Port-en-Bessin, tiny figures standing sentinel on a distant bridge take the eye far out to a Normandy sea as becalmed as the skies above – completely still and yet somehow composed of thousands of bright dots.

Seurat’s seas are counterintuitive. How could they not be? For other French painters, the sea sweeps and froths, waves ruffling its surface even in the heat of July. Its thrill is tidal, not just aqueous. For Seurat the sea is level, depthless and perpetually immobile. Nobody swims in it, nobody drowns. It is an obverse empyrean: the sky turned upside down.

It is also outstandingly beautiful. The first Seurat show in this country for almost 30 years, Seurat and the Sea is captivating in all its strangeness. It turns out that the artist (1859-91) painted more seascapes than any other subject. There were 24 “marines”, before his tragic death of what might have been diphtheria, at the age of 31. The Courtauld has gathered 17 from across the world, as well as many of the brilliant and free oil sketches.

After working all winter on large canvases such as La Grande Jatte, Seurat would cleanse his eyes of the studio, he wrote, “to translate as accurately as possible the bright light” of the coast. For five summers, he took the train from Paris to small ports, prosaic and contained compared with Monet’s wide-open shores. And what he sought is immediately apparent at the Courtauld: visions of marine light, clear, reflective or opalescent, pale at midday, golden in the afternoon, suffused with pink or hazy grey at dusk. In some of the sketches, light does away with the divisions between sea and air.

Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp (1885). Main image: ‘the most beautiful painting in the exhibition’, Seurat’s The Channel at Gravelines, Evening (1890)

But just as the light changes from picture to picture across the galleries, so the compositions shift all around you. Seurat never aims to ingratiate. He will fill the foreground with an ungainly rock, block the view behind a tangled bush, hide the evening sun behind a cliff so that its radiance is thrown out across the ocean without any obvious source.

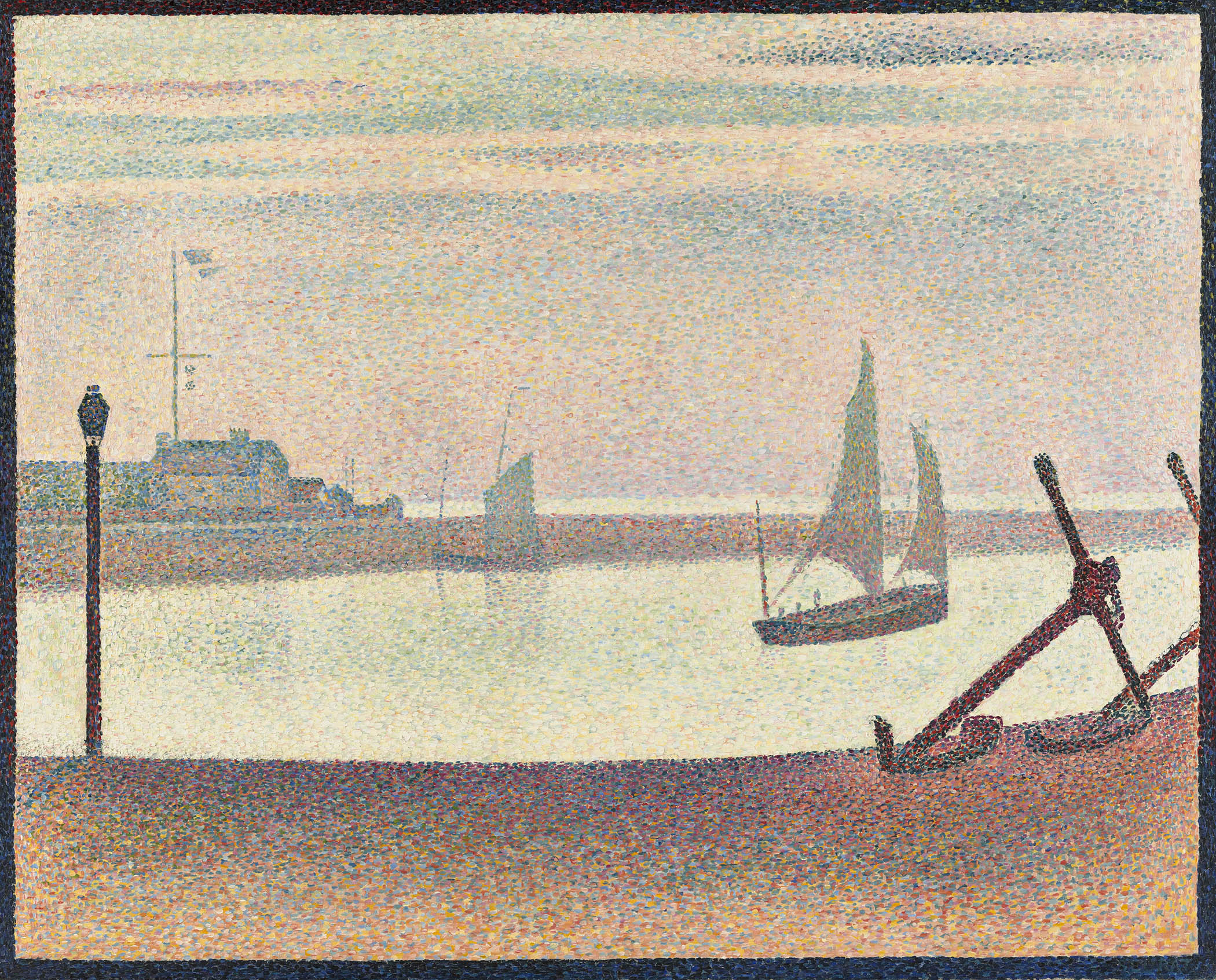

His port scenes are unusually accurate – the Courtauld displays period postcards for reference – yet his shapes can be so outlandish. A watchful bollard, inserted into the foreground of Entrance of the Port of Honfleur – on loan from the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, thanks to a relaxation in its longstanding rules – throws a weird cruciform shadow on the quay. Yachts that might tilt in the wind come straight at you like blades. Sails form into crescents, and in the great painting The Channel of Gravelines, borrowed from Indianapolis, the sandy quay – in reality straight – recedes into the distance in an exhilarating parabola.

So much for the supposed rigidity of pointillism. The science, based on Chevreul’s studies of the behaviour of complementary colours, was always quite conventional compared with the art. And the very first work in this show sidesteps those theories right away: the bay at Grandcamp is sea-green, the sky blue, the land brown, if in each case scattered with white and grey.

What strikes is something else altogether: the strokes lie on the little wooden panel so clearly that each can be numbered. Short vectoring marks, this way and that, invoking a horizon without actually describing it – how hard it must have been to deny himself the odd line – they are so loose that the wood glows through. The whole surface is alive.

Made using a portable paintbox hooked on a thumb, with a slot for such panels, these little studies “were his greatest joy”, according to a fellow artist. But even the finished canvases grow freer and wilder each summer. Steam rising from a ship’s funnel dissipates in a murmuration of tiny dots, before reforming elsewhere into a hazy mast. The glints on a ship’s hull are a running hem of orange on navy blue. Lozenge, pixel, hyphen, cross-stitch, blue spot inside green circle, like a tiny semblance of Monet’s water lilies, Seurat very rarely uses the fabled dot.

Everyone has departed. Peace descends. Masts, lampposts and sails become upright abstractions, held in perfect balance with the horizontal bands of water, harbour and sky

Everyone has departed. Peace descends. Masts, lampposts and sails become upright abstractions, held in perfect balance with the horizontal bands of water, harbour and sky

The pictures go awry when stick figures appear in the foreground, or when Seurat gets diverted by a fish market. Any temporary buzz gets in the way of his seascapes, where time stands silent and still. The most beautiful painting in this exhibition, on loan from theMuseum of Modern Art in New York, shows Gravelines at twilight, where the waters have quietened to a silvery brightness and the sky above is pink-tinged with dying light.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Everyone has departed. Peace descends. Masts, lampposts and sails have become upright abstractions, held in perfect balance with the horizontal bands of water, harbour and sky. Seurat’s studies for this work, shown alongside, isolate and contemplate each element. The composition is so meticulous, so careful in its exacting deliberation, that you hardly need the pointillist border Seurat added later to remind you that this is, above all, a painted scene.

But what is the painting and what the scene? A contemporary critic once wrote that Seurat’s art required equally careful attention, to separate stroke from image, and so it seems from these works. Reserved, so private scarcely anyone knew he had a mistress when he died, Seurat created seascapes characterised by deep and solitary attention. He was only 30 when he made the last, and there is no hint of what was to come. Intense absorption is what the paintings register, what they took to make and what we receive.

A 10th Lucian Freud show in as many years may seem excessive, but the latest exhibition at least promises a more intimate look at the artist’s mind and hand at work on paper. This is partly fulfilled in scratchy love notes and phone numbers, but mainly through sketchbooks, drawings and etchings. Nobody going to the National Portrait Gallery’s Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting, however, will be disappointed to find more than 100 paintings.

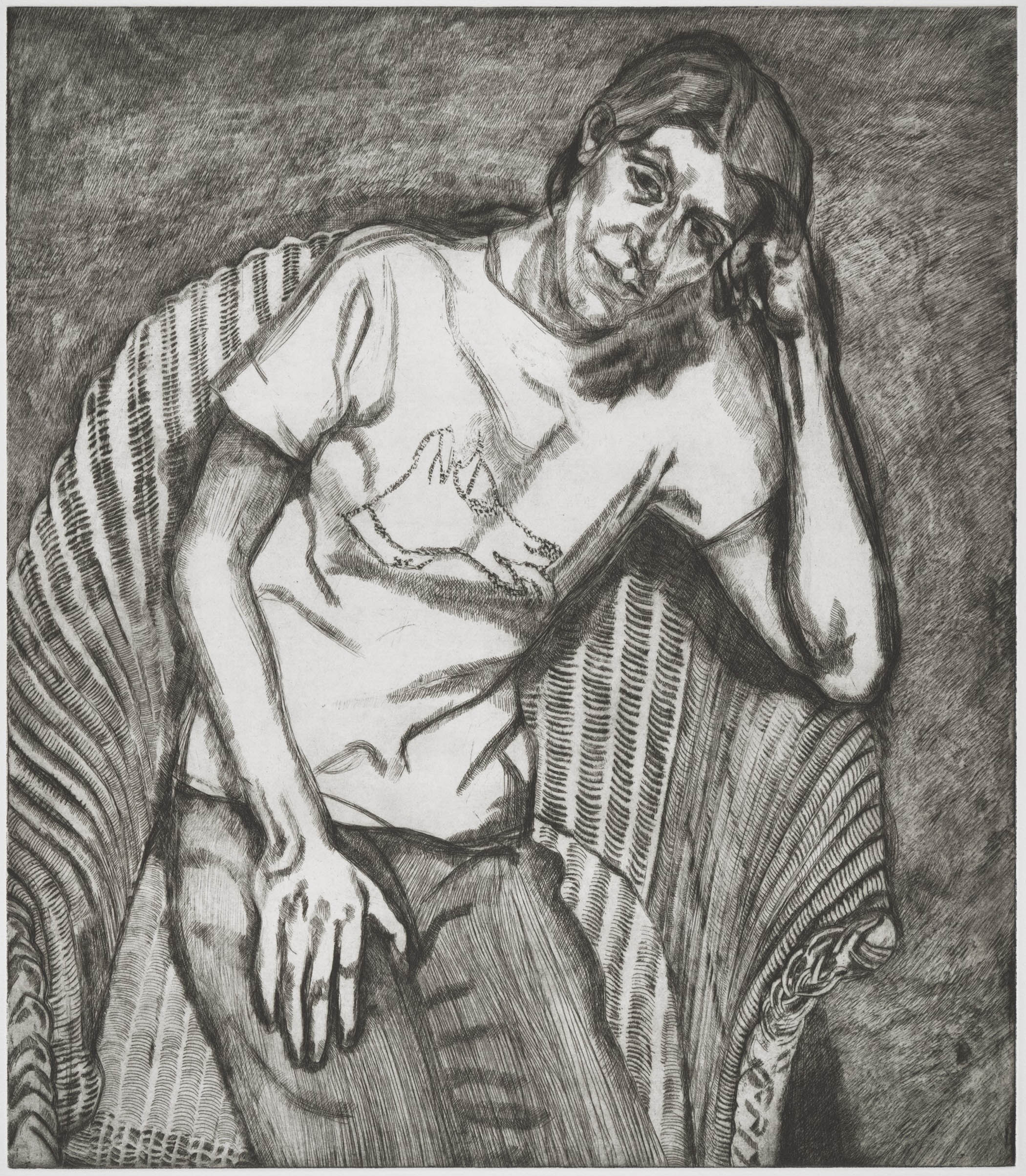

Bella in her Pluto T-Shirt, 1995, by Lucian Freud

It is not obvious that the graphic works are so distinct in any case. Freud’s depiction of people, in any medium, are not quite (or not often) portraits. He worked from the life but not from their lives so much as their animal presence in his studio. So while it is good to see early drawings of Düreresque thorns and Ravilious-like leaves, and to witness the punctiliously graphic aspects of his 1950s paintings of lovers such as Caroline Blackwood, it does not seem much of a revelation to behold the office workers, fellow artists, models, magnates and many offspring in pencil instead of paint.

But the larger the show, the greater the opportunity to catch the tone of these works. Some of Freud’s most famous, and infamous, paintings are here: from his own profound self-portraits, dismayed by the mirror, or defiant in old age, to the jowly little Elizabeth II. It bears saying, yet again, that the tenderest portraits here are of the beloved whippets Joshua and Pluto, and the strongest likeness is of Freud’s daughter Bella.

But Freud’s drawings and prints of the shrewd Lord Goodman, in all his pomp, quiver with the very conversational vitality Goodman discovered in Freud: two magnificent minds in equal tension.

Seurat and the Sea is at Courtauld, London, until 17 May

Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting is at National Portrait Gallery, London, until 4 May

Photographs by Museum of Modern Art, New York/Tate/National Portrait Gallery