Portrait by Rafa Jacinto

In the magnificent medieval civic hall of the Palazzo della Ragione in the main square of the walled city of Bergamo, my name rings out from amid a 30-strong scrum of Italian journalists wielding a battery of cameras, microphones and smartphones. “Andy!” calls Maurizio Cattelan, the artist best known for taping a banana to a wall, and he reaches out to me as if I offer some form of sanctuary from the media maul. “It’s madness,” he whispers conspiratorially, as he draws close. “Crazy! The same questions over and over again!”

The headline artist in the biennial Thinking Like a Mountain organised by Bergamo’s gallery of modern and contemporary art (GAMeC), Cattelan is previewing to the Italian press his marble sculpture November, which he had shown to me the previous day in far more sedate circumstances. It depicts a homeless man lying on a park bench wetting himself – the stream of water leaking onto the floor from his open fly, a tragicomic reworking of the classical Roman fountain.

The self-styled enfant terrible of modern art is now 64, though he retains a lithe youthfulness as he skips around eluding the repeated demands to explain the meaning of Seasons, the title of his exhibition for the biennial.

It’s a scene straight from a Fellini film, something you might associate with a rock star but seldom a visual artist. Hailed as a sublime talent and condemned as a cynical rogue, Cattelan is the rightful heir to the polarising reactions that Marcel Duchamp inspired back in 1917 with his urinal entitled Fountain – it’s no coincidence that one of Cattelan’s most high-profile works was the fully operating gold lavatory that was stolen from Blenheim Palace in 2019.

One, an installation in Maurizio Cattelan’s Seasons exhibition, features a sculpture of a boy atop a statue of Giuseppe Garibaldi

The questions in which the pioneer of dadaism delighted also attend Cattelan’s exhibitions: does his true creativity lie in his work or his self-promotion? Great artist or a con artist? A sly 2016 documentary, Be Right Back, made in collusion with Cattelan, sought to challenge his mythology while only adding to it. In one scene, the gallerist and collector Adam Lindemann said: “I think he’s probably one of the greatest artists that we have today, but he could also be the worst. It’s going to be one or the other. It’s not going to fall in the middle.”

The man himself seems to revel in the uncertainty he generates. He insists he is not a conceptual artist, although his ideas often overshadow his creations. He has even said that he is not an artist at all – he does not have a studio and the fabrication of his work is subcontracted – while maintaining that what he produces is art.

Writing last year in New York magazine, the art critic Jerry Saltz called him “an astonishing icon-image-object maker”. His work, Saltz wrote, “courts a beyond good and bad analysis. He always fails and succeeds at the same time. This creates another category.”

Related articles:

As The Observer’s art critic Laura Cumming noted of the notorious Victory Is Not an Option show in 2019 at Blenheim Palace: “Cattelan has always been a curious figure in contemporary art. His sculptures are one-liners, cartoons in three dimensions, almost abrasively direct ... But what counts is context, every time, precisely where the artist places these provocations.”

He certainly possesses a gift for recruiting surroundings to his cause. Perhaps it’s an outsider’s eye, the perspective of someone who knows all about upending social conventions and expectations. Over lunch last week in a chic Bergamo restaurant, he told me the story of his idiosyncratic rise to international recognition.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

A working-class altar boy from Padua, he grew up in a home where the only art was religious iconography; he didn’t attend university or art school. His father was a lorry driver and his mother a cleaner who spent long periods in hospital during his childhood, a result of the lymphatic cancer that would eventually kill her when Cattelan was in his early twenties.

His first job was selling Catholic imagery at his local church when he was 12 and his first act of iconoclasm was to draw moustaches on statuettes of Saint Anthony. He had lost his faith by then, he says, a subject he returned to in his 1999 piece La Nona Ora, a statue of Pope John Paul II felled by a meteorite. He suggests that, despite some protests from the church, the work wasn’t intended as an anti-Catholic statement. As he once put it: “The pope is more a way of reminding us that power, whatever power, has an expiration date, just like milk.”

Cattelan went on to work in a series of jobs in which he had little interest: caretaker, postman, an orderly in a hospital and an assistant at a morgue. He could not abide rules. At the hospital, he would cut himself, he says, so that he could take time off and travel.

In his twenties, he began fashioning little pieces of furniture that he would take to Milan to sell to Lucio Zotti, the manager of a furniture shop who would become his artistic collaborator. Cattelan says there were 15 years of uncelebrated labour before his apparently sudden breakthrough in the 1990s. “I always felt like I had imposter syndrome. But as they say, as long as nobody is complaining...” he breaks off with a little chuckle. “Even when things changed in terms of recognition, I still thought something was wrong. I said sooner or later [it’s bound to end], but it’s still working.”

This self-doubt did not prevent him from taking some bold risks when opportunities did arise – though they were risks, by his own reckoning, that were born out of insecurity and desperation. For his first gallery show, he failed to produce any work and visitors were greeted with a small sign that read Torno Subito (Be Right Back).

On another occasion, he removed a fellow artist’s work and presented it as his own. When he was invited to show at the 1993 Venice Biennale, he sold his space to an advertising agency that erected a giant ad for Schiaparelli perfume. He called it Working Is a Bad Job. (As with Duchamp, his titles are asked to do a lot of work, especially when, as in the case of Torno Subito, they are the work.)

The following year, he debuted in New York with a show at the Daniel Newburg gallery featuring a live donkey tethered beneath a crystal chandelier. It was closed down after a day because of neighbours’ complaints about the braying and health concerns regarding the animal’s droppings (but that didn’t stop him from restaging it 22 years later at Frieze New York).

By such attention-grabbing stunts, or ingenious indolence, Cattelan earned a reputation as a prankster; someone who seemed willing to go a long way to avoid the hard graft of solid production, and then presented his minimalist effort as a commentary on the pretension and venality of the art world.

Had this notoriety been his only mode of expression, he would most likely have run his course many years ago. But he has also frequently shown himself capable of genuinely original and unsettling work. One notable example was the 1996 installation Bidibidobidiboo, in which a stuffed squirrel lay slumped across a kitchen table, a squirrel-sized handgun at its feet on the floor.

Superficially amusing, it also packed a gut-punching pathos, a bleak scene of suicide enacted in a mundane and yet surreal setting. The fact that the table and chairs were based on those in Cattelan’s childhood home pointed to a parallel biography, the constrained life he didn’t lead.

Referring to some petty crime (forging train tickets) he committed in his youth, he tells me: “Art saved me twice from a miserable life. From a life of slavery and probably from the underworld – though I didn’t have the stamina or the evil genius to be in the underworld, so that probably would have been a bad ending.”

Cattelan’s gold lavatory, America, was stolen from Blenheim Palace while on loan from the Guggenheim

If art freed him from a life of crime, then crime later collected the debt by coming for his art. In September 2019 a gang of thieves broke into Blenheim Palace, which had taken his gold lavatory artwork America on loan from the Guggenheim. In five minutes, the gang managed to liberate the loo from its plumbing and moorings and drive off into the night, leaving only the security camera footage of the escapade.

Police believe the lavatory was immediately taken to a number of locations, melted down and sold off. When Cattelan previewed the piece, he spoke of how he liked its democratic spirit: “Whatever you eat, a $200 lunch or a $2 hot dog, the results are the same, toilet-wise.”

Some of the gang were later caught, charged and, earlier this year, convicted. In court it emerged that one of the guilty, Michael Jones, had availed himself of the gold lavatory’s facilities on the first day of the exhibition. Asked what it was like, he replied: “Splendid.”

What did Cattelan make of this Guy Ritchie-like drama?

“This is what you hope for!” he says. “Because a mediocre work became a good work. If you don’t produce the narratives yourself, you hope that someone will complete the work.”

So the burglary felt like a continuation of his vision? “Oh yeah, yeah. I mean, I cannot say that I’m a supporter of theft. But I remember before the opening saying, it would be nice if sooner or later this work is stolen.”

Because it was mediocre?

“No, it was an interesting work but it was missing some charm. Before it had just the scatological side, but now it has a Hollywood side.”

Cattelan doesn’t like giving interviews. He grants very few, because, he says, he only ever works out what he ought to have said the day after he’s spoken. He wants to be quotable. “Aphorisms are fantastic!” he says.

GAMeC’s director, Lorenzo Giusti, mentions to me a project to promote Bergamo’s scientific district to which Cattelan has contributed a slogan on a poster that is visible from the main highway: “Accelerate. Life is short.” I’m not sure it would pass the UK’s health and safety regulations, but I ask Cattelan if that’s his philosophy.

“I would say it’s an encouragement to take life seriously because you don’t have so much time,” he says.

Some of his conversation can seem on the page unsubtle, even gauche, which is partly accounted for by English being a language that he came to relatively late. He didn’t speak a word, he says, when he first went to New York in his thirties, though he now divides his time between that city, Milan and global travel. But what’s missing in the text is his cinematically expressive face. Dominated by a large connoisseur’s nose, it can look grave and thoughtful, and yet his features are ever-ready to crease into amusement; he adds a running commentary of eye rolls, raised eyebrows, pouts and other comic gestures to his verbal output.

Watching him pose for our photographer, you see a natural physical comedian. It’s this exuberance that can sometimes make his work seem a little too playful, as if its main thrust is the punchline. Equally, it can also mask surprising depths. At Bergamo, he is showing five works in three different locations. Three pieces are new, one is a reworking of Him, his 2001 wax model of Hitler in a grey suit kneeling in apparent penitence. The difference with the new version, retitled No, is that the figure now has a paper bag over its head.

Cattelan tells me that the bag was a solution he reached when the Chinese authorities refused permission for him to show the original because it contravened the country’s strict political censorship.

“What about if I put a paper bag on top?” he asked an official. “Fantastic!” came the reply.

“It started as a way to overcome a problem but when I saw it,” he says. “I said ‘Wow! This is a new work.’” And in a way it is. It’s not just an absurdist comment on censorship but there’s also a sinister suggestion of something else: unspeakable infamy, the hint of torture, an evil too potent to be seen. The work it shares a room with is entitled Empire and features a house brick stamped with the word “Empire” inside a glass bottle. “The unit of every empire is a brick,” says Cattelan. “Also, I don’t know, it’s a message in a bottle...”

He trails off, as if all too aware of the perilously short distance between succinct and facile. On the way to the next location, I ask him about the legal controversies that form a kind of recurring motif in his oeuvre. Last year, lawyers acting for the British-American artist Anthony James sent Cattelan a legal letter suggesting he had a plagiarism case to answer under the terms of the copyright act.

Cattelan had just opened his show at the Gagosian gallery in New York in which the main piece was 64 reflective gold panels pockmarked with bullet holes. James also had a show elsewhere in New York featuring his Bullet Paintings, 18 stainless steel panels also pocked with gunshots. “There’s no chance that he hasn’t seen them or that they haven’t come to his attention,” James was quoted as saying. Cattelan maintained a diplomatic silence at the time, save mentioning to the New Yorker critic Calvin Tomkins that the similarities were “uncanny”. The artist still seems surprised by what he insists was a coincidence, but dismisses James’s legal manoeuvrings by saying – accurately – that there are a long line of artists who have used bullet holes to creative ends.

What about Daniel Druet, though, the French model maker who created the Hitler sculpture, as well as the pope – not to mention the bust of the former model Stephanie Seymour commissioned by her billionaire husband, Peter Brant, and informally known as Trophy Wife? Three years ago, Druet tried unsuccessfully to sue Cattelan, claiming that he deserved recognition as the true artist of the works. Did the Italian feel betrayed?

“No,” he says. “But you have to defend yourself, otherwise you lose your paternity. It wasn’t that he wanted to be recognised as someone who helped. He wanted to be the artist; that was never going to work.”

The word “paternity” is telling. Cattelan doesn’t have children. “I have a family of puppets,” he says. Perhaps as a result, there remains something rather childlike about him: open, curious, a youthful spring to his movements. It’s notable that many of his artworks depict children.

“Childhood,” he once said, “this strange place where traumas happen and you dream incredible dreams, is a place I always return to.”

He was speaking then in relation to arguably his most disturbing work, a 2004 installation that featured three lifelike, or more precisely deathlike, children hanging in nooses from a tree in a Milan square. One passerby was so offended by the suicidal sculptures that he got a ladder and cut down two of them. Unfortunately, as he tried to do the same with the third he lost his balance and fell to the ground, ending up in hospital with concussion. The local Milanese council then debated whether the installation was art and if the saboteur should face criminal charges.

Although Cattelan’s friend Massimiliano Gioni (who has sometimes pretended to be the artist in interviews) hyperbolically compared the sabotage to the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, the whole episode seemed to be a quintessential Cattelan happening – full of unpredictable turns and public drama.

Gioni, artistic director of the New Museum in New York and the Nicola Trussardi Foundation in Milan, is not the only art world figure Cattelan has recruited to his cause. He dressed the Parisian dealer Emmanuel Perrotin in a giant pink penis outfit with bunny rabbit ears at his 1995 show at Perrotin’s gallery. And he once affixed his Milan dealer Massimo De Carlo to a gallery wall with heavy-duty duct tape. The dealer had to be cut loose when he began struggling to breathe.

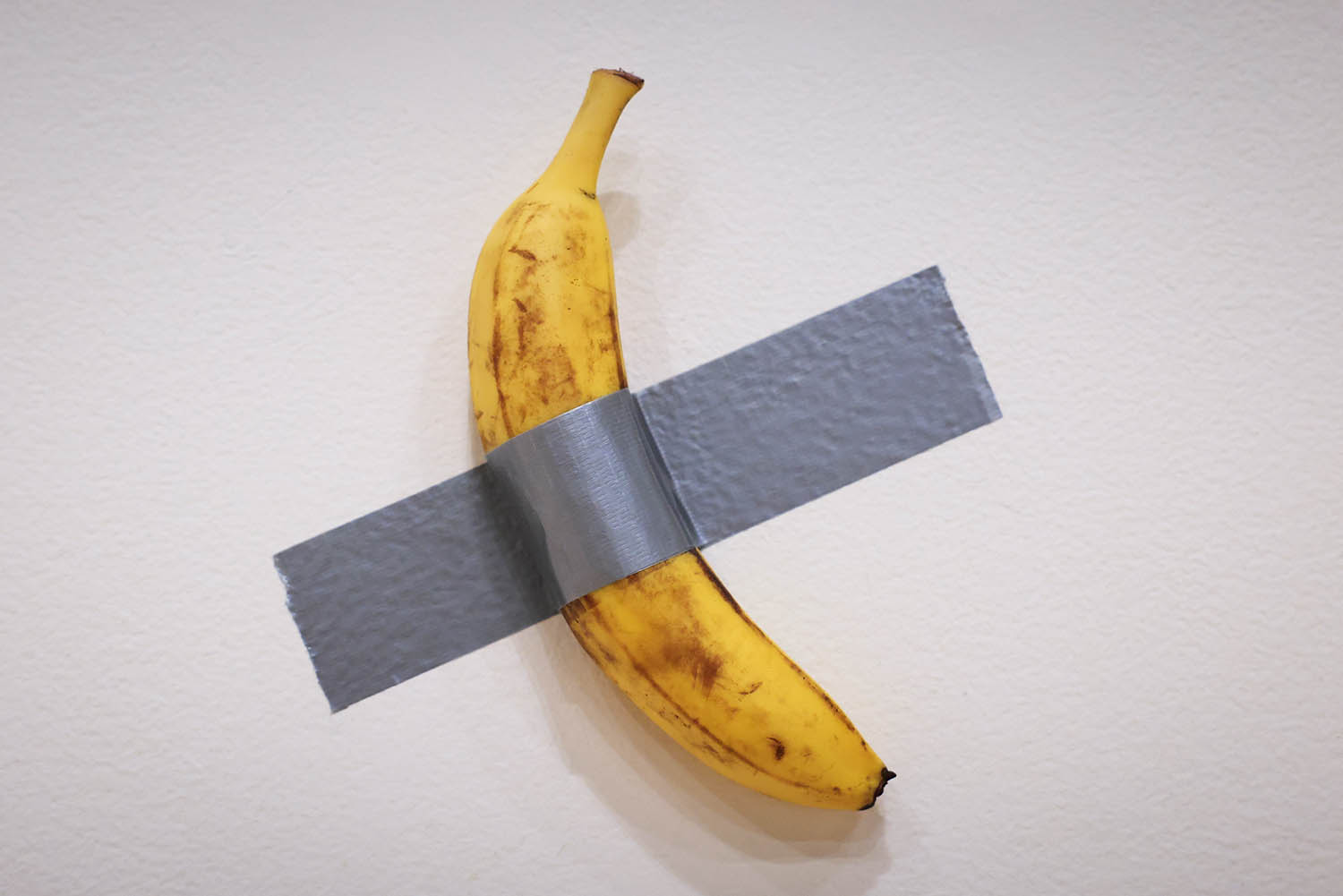

Cattelan credits Comedian, his 2019 work featuring a banana taped to a wall, with ‘refreshing his image’

De Carlo was destined to be trumped in 2019, however, by the banana that Cattelan duct-taped to a wall at Art Basel Miami Beach. Cattelan is still grateful for all the noise and publicity that ensued. “I would say it’s a work that refreshed my image in the new century. It will haunt me for ever but also it’s the work that gave me a second chance.”

Did he feel he was in need of one?

“You know,” he says, “we are all afraid of dying. Our society is based on consuming tons of stuff that will make us younger, thinner, more beautiful. When you get over a certain age, it’s a fight, a war that you never win.”

In 2011, he staged a retrospective of pretty much all his work at the Guggenheim in New York and hung it all from the ceiling. It was intended, at the time, as his swan song, his farewell to the business of producing art.

“I thought it was a final retirement,” he says. “At a certain point, they should kill the artist because after that [point], he starts to repeat himself.” He was exhausted by the stress of having to come up with something new. He returned after five years. “You must solve your ego problems to retire, but I didn’t,” he admits. “That’s why I came back.” It wasn’t just the desire for further recognition that drove his return. There was also another concern. “The market doesn’t like it when you stop producing,” he explains. “There is no interest to support you and you cannot make money in the secondary market.”

Which brings us to the warping effects of commerce on contemporary art, the gravitational pull of big money and the aesthetic demands of what is, in essence, a form of commodity trading. The taped banana, entitled Comedian, came in a limited edition of three, each of which sold for $120,000 (the three bananas together cost less than a dollar). Last year, the Chinese-born cryptocurrency trader Justin Sun bought the second of the three for $6.2m. It seems emblematic of these overtly corrupt times that Sun also bought $19m of the $TRUMP meme token, a digital coin associated with the US president, not to mention the $75m million he has poured into the World Liberty Financial – another crypto venture that directly benefits Trump-owned entities.

Given that some of Cattelan’s works – such as the gold lavatory America”, made on his return in 2016, and the bullet-ridden gold panels of Sunday – are seen as satires on the violence and greed of capitalism, there are surely some uncomfortable ironies in these billionaire acquisitions. The artist says he has no relationship with his collectors, and neither does he personally profit from auction prices on the secondary market. Once his pieces are bought, he says: “I consider them orphans. They have to fend for themselves.” His creative motivation, he says, is not materialistic. “My life hasn’t changed. I still have the same bicycle.” He pulls back his shirt sleeve: “I don’t have a watch. I don’t hang expensive art on my walls.”

Perhaps, but he leads a transatlantic life infinitely more comfortable and liberated than he could ever have envisaged as a boy. What compels him to work, he says, is essentially psychological in nature. In art, he confronts himself with aspects of his past of which he was not previously aware, at least consciously. There is a therapeutic quality, in other words, but it comes at a mental cost. If he could escape his ego, he says, he would no longer have to “sit down and try to hurt myself with anxiety”.

We visit the church-like Oratorio di San Lupo, where his giant white marble eagle lies sprawled on the tiled floor. The sepulchral setting lends the piece – a subversion of fascist symbolism entitled Bones – a ghostly power. Similarly, the vast historic space of Palazzo della Ragione adds a majesty to November. The face of the homeless man is based on Cattelan’s late friend and collaborator Zotti, whose son is putting the finishing touches to its presentation. I ask Cattelan if he feels nervous before the opening of a show.

“No, it’s the best time. It’s afterwards I don’t like, when everyone tells you what you should have done.”

The following day, Cattelan is looking fatigued by the attention and he invites me into his chauffeur-driven limousine, while the rest of the press pack are ferried by several small buses to the next location on the tour. In the car he talks about how the Young British Artists of the late 1980s used their group strength to converse with the media and how people such as Takashi Murakami are now using digital media as a means of interface. I say that he seems to manage quite well with old-fashioned methods. He shakes his head. “I consider myself a beginner, naive in communication.”

We arrive at One, the final work at the Rotonda dei Mille, Bergamo’s equivalent of Trafalgar Square. In the centre is a huge statue of modern Italy’s founding father, Giuseppe Garibaldi, that has stood in this location since 1922. On his carved shoulders is mounted Cattelan’s contribution, a young boy in a red top with the index finger of his right hand pointing upwards to the sky.

“The old and the new,” says Cattelan, looking up at what is a triumph of humour and engineering over civic red tape. Within seconds, the army of local journalists arrives and once again Cattelan is buried beneath their outstretched recording devices, all asking him the meaning of the pointing boy. I make my way through the scrum to announce I have a deadline to meet and a plane to catch. “It doesn’t matter if what you write is positive or negative,” he says, as he bids me goodbye. “Just make sure you pump it up.”

As I turn to leave, he calls me back. “Andy, remember – pump it up!”

Seasons is part of the Orobie Biennale project in Bergamo.

Images by Rafa Jacinto, AFP and Leon Neal/Getty