The “Two Roberts”: so they were known, from their native Scotland to 1960s Soho, a couple who lived and worked together before homosexuality was eventually decriminalised. Colquhoun (1914-62) and MacBryde (1913-66) met at Glasgow School of Art in 1933 and were never apart. Their relationship survived meteoric success, depression and eventual poverty, ending only with Colquhoun’s death in 1962, of a heart attack brought on by alcohol and overwork at 47.

Dramatist John Byrne wrote a two-handed stage play in homage. The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art mounted a substantial retrospective in 2014. But England has mainly ignored them. Now the Scottish author and broadcaster Damian Barr has written a novel, The Two Roberts, and simultaneously curated the first English show since Colquhoun’s premature death. The captions are as joyous, as loving and open-hearted as his novel, and as tenderly written. But the art is darker, more wayward and knotted.

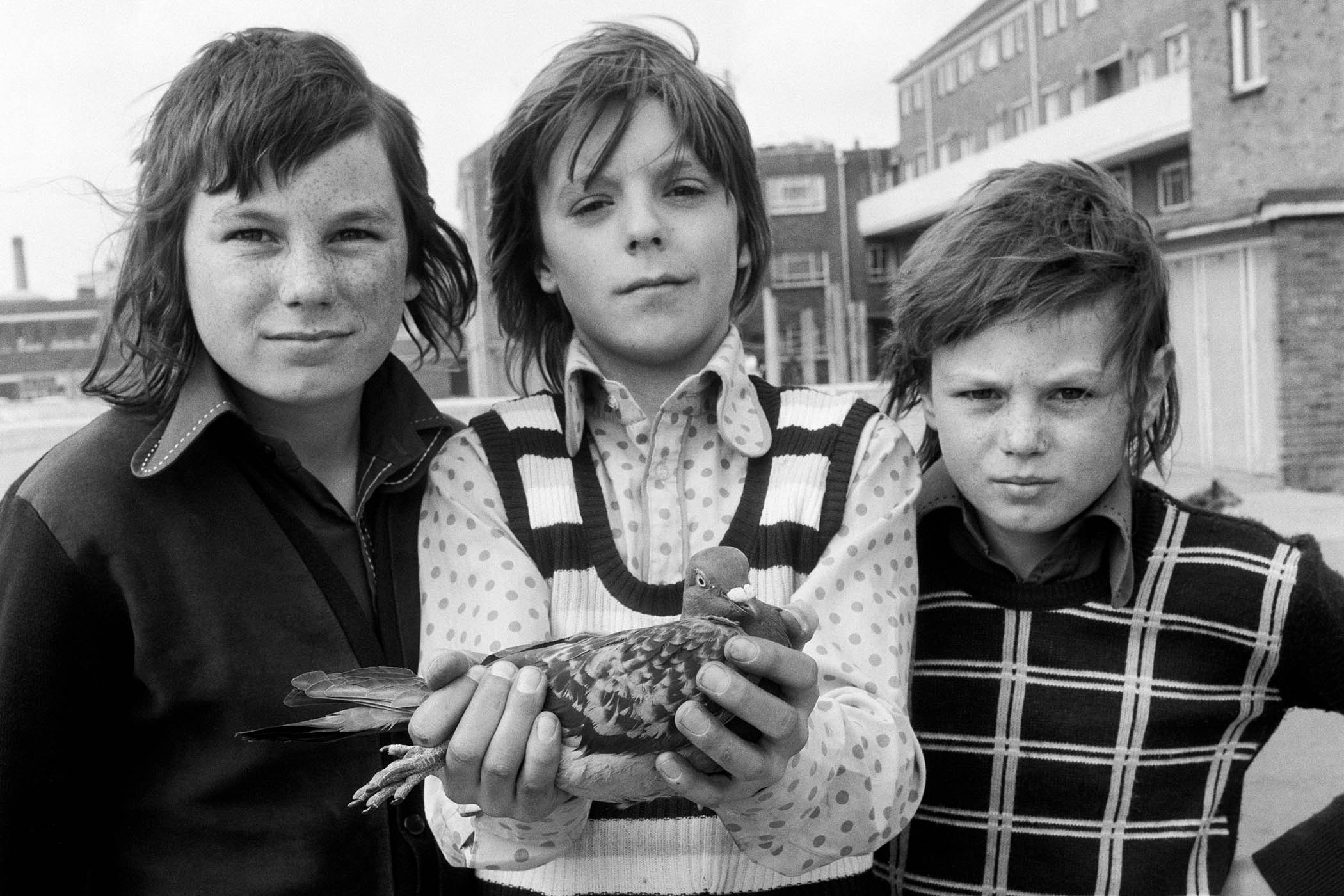

Both artists came from Ayrshire and left school at 15. There are hints of Colquhoun’s hard childhood in his powerful painting The Potato Diggers, with their furrowed heads and red-raw working hands. Some memory of a woman with a goat recurs, the wild creature on equal terms with its bent and stoic keeper. In a lithograph from 1951, a boy balances a bird in one hand and its prison of a cage in the other. Colquhoun’s unyielding father kept birds in the back yard. As Barr observes, the artist knew the longing to fly free.

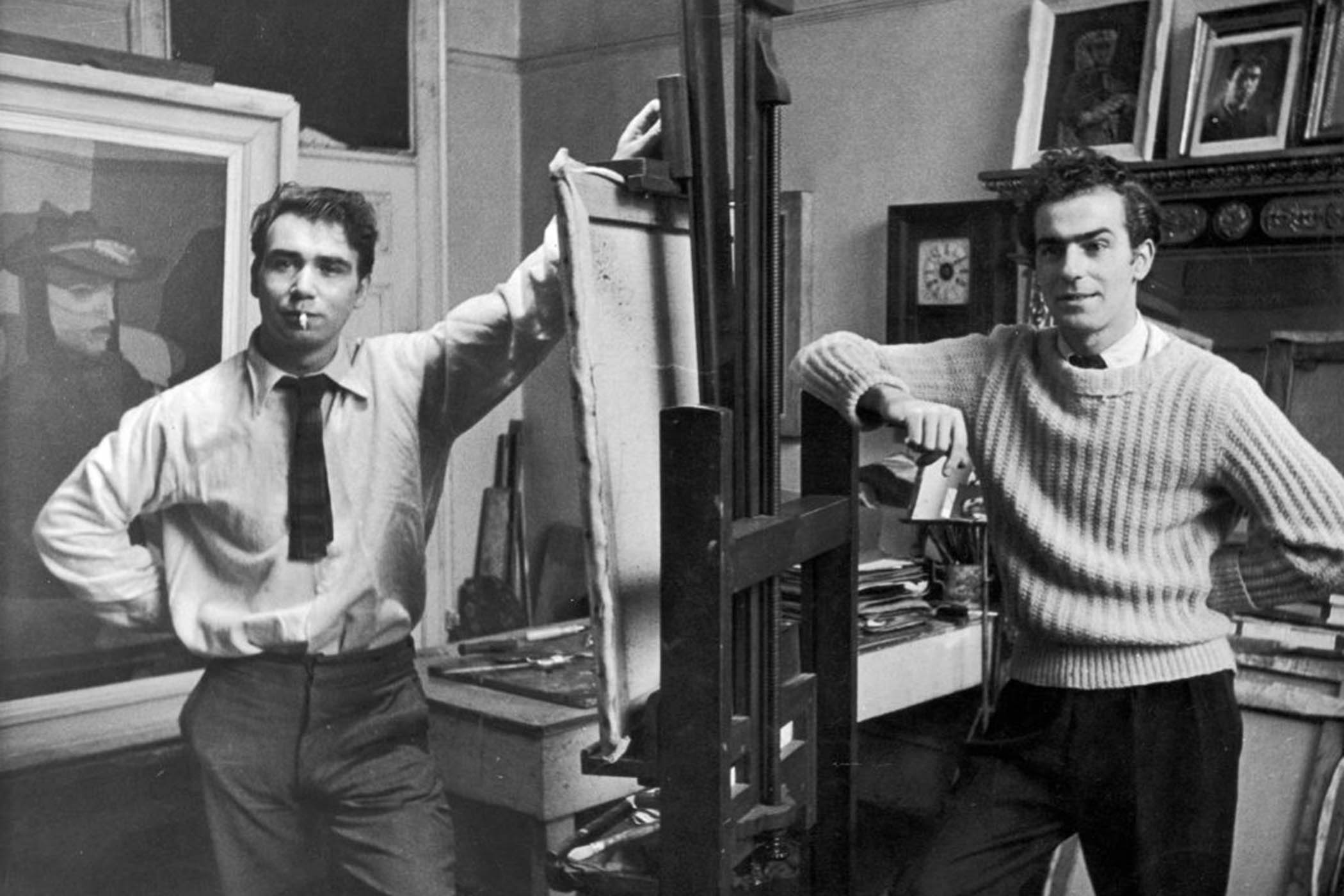

Colquhoun’s Woman with a Goat. Main image: The Two Roberts in their Kensington studio

He was such a star at Glasgow, and so inseparable from MacBryde, that the art college doubled his travelling scholarship money so the two men could journey through Europe together. One of the earliest works here is his ink drawing of MacBryde reclining in a Roman bedroom like Manet’s Olympia. Their tutor, Ian Fleming, paints them together with a great emphasis on Colquhoun’s splayed legs, as if he had some knowledge of their secret relationship. Colquhoun is long faced and pensive, MacBryde evidently more sociable. Some sense of their opposite natures is reflected in this show, where it seems as if MacBryde is too gregarious to paint.

For he doesn’t materialise until halfway through, after the second world war, with still lifes of curvaceous mandolins rhyming with halved peaches or fish heads eyeing us, quite cheerfully, from platters. Colquhoun, meanwhile, has been conscripted – an angular but refined self-portrait in pencil shows him shorn and dangerously underweight in army uniform. An arsenical green and yellow painting of two women grieving towards the war’s end looks, as Barr observes, as if it were made by candlelight during a London blackout.

Barr’s captions are telling and generous. Alongside Colquhoun’s monumental post-cubist Woman Ironing, from 1958, he reminds us that the Two Roberts cared about their appearance but were too poor for an iron, MacBryde using the back of a heated spoon on their clothes instead. He is excellent on their great adventure through the galleries of Mayfair, Picture Post cover stories and Muriel Belcher’s Colony Room club, along with Bacon, Freud and other Soho alumni. It is a pity that you can’t make the Two Roberts out in Michael Andrews’s group portrait of the bar; or indeed that there are quite so many paintings by Jankel Adler, John Minton and others to swell a progress.

MacBryde’s Apples on Paper

Lefevre Gallery, shouts a poster, is showing Bacon, Sutherland, Freud and Nicholson alongside the Two Roberts in 1946. Colquhoun’s startling Woman with Leaping Cat, the creature struggling from her grasp, is bought by the Tate. Barr has sought out many unseen figure paintings by Colquhoun, rather than more famous works like Leaping Cat, including his wonderfully human The Three Graces, looking like Ayrshire land girls.

This show is unlikely to dislodge the old cliche of McPicasso and MacBraque, or the idea that one painted people and the other only still lifes. In fact, MacBryde’s tabletops, with their ripe split melons, textured surfaces and gorgeously graphic outlines, seem to prefigure the art of Patrick Caulfield by a decade. But it is impossible to know what the Two Roberts would have painted next, after all the years of Scottish modernism that fell out of fashion in the late 50s with abstract expressionism, minimalism and pop.

Related articles:

The show’s ending is intensely moving, as Barr leads us into Ken Russell’s 1959 film portrait where you see Colquhoun alive and hard at it, still bringing cups of tea to MacBryde, painting in the next room. But Colquhoun’s hands are shaky, and he has trouble steadying the brush. Alcohol is taking its toll.

Colquhoun died at 5am in a makeshift studio in Museum Street, London. He collapsed in front of his easel. MacBryde, devastated, adrift, fetched up in Dublin without a fixed address. Four years later, he was killed in a hit-and-run incident outside a pub. He was 52.

Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun: Artists, Lovers, Outsiders is at Charleston in Lewes, East Sussex, until 12 April

Photographs by Bridgeman Images/Pallant House Gallery/Felix Man/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy