In the days leading up to this year’s Frieze art fair, I had been feeling apprehensive about my place in the art world. I’d dropped out in 2018, closing the gallery I had started four years previously. In 2020, my former friend and business partner Inigo Philbrick was arrested by the FBI. He later pleaded guilty to wire fraud amounting to $86.7m and was sentenced to seven years in prison. (He was released at the beginning of 2024.)

I wrote a book, All That Glitters, about Philbrick’s crimes in which I tried to explain the realities – and secrets – of the market. For the most part, the book was well received but its lack of discretion (considered chief among art dealing virtues) made me some enemies too. I knew there would be people who would be wary of talking to me and I wondered what new secrets or old ghosts I might encounter over the coming days.

The art world is about many things: money, power, secrecy – even sex. But more than anything else, it’s about access. Until the evening before Frieze opened, I’d been feeling smug: for the first time, I had been sent a coveted 11am VIP invitation. (The “V” in VIP diminishes in impact throughout the day: 11am for the big collectors and a shiny smattering of celebs; then 1pm for artists, their friends and families; followed by 5pm for basically anyone who has the phone number of a gallerist.) I was not at all surprised, however, to learn that, on that Tuesday evening, there had been an even more exclusive exclusive event for guests of Deutsche Bank Wealth Management, a longtime sponsor of the fair.

At 11am, the queue of people winding their way up the gentle ramp to the fair entrance on the edge of Regent’s Park was quiet, pensive even. I had been expecting a tidal wave of fat cats; the reality was somewhat sludgier, slow-moving, sediment-rich. There was an air of consternation among my fellow VIPs: these people are not the queuing kind. In front of me, a vulpine Frenchman distracted himself by playing Sudoku on his phone, furiously swiping away adverts for a free Paint by Number app. All around me, people greeted each other with air kisses, A-frame hugs and elongated “daaaahhhlings”. As the line finally started to move, a woman in a wheelchair, dressed all in black, was stuck like a rock in a stream as she desperately tried to find her invitation.

After a post-pandemic rush of money into the art market, the mood has been down lately. In recent weeks, global mega galleries David Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth had both reported a near 90% drop in earnings at their London outposts; last year, Sotheby’s, the international auction house, announced pre-tax losses of $248m. Gallerists I had spoken to were nervous.

Pandemonia, a persona created by an anonymous artist, holds court at Frieze

Directly in front of the entrance to the fair were two galleries, one called the Pit, the other called Soft Opening. Nearby, in Thomas Dane Gallery’s booth, was a footpump-operated kinetic sculpture by the artist Michael Landy: the pump, which could be employed by anyone who cared to use it, made the sculpture repeatedly hit itself in the head. Sometimes, life provides its own metaphors.

The fair’s big tent seemed designed to be a hermetically sealed plutocracy cut off from the worries of the outside. There’s no need to worry about someone nicking your Patek Philippe here, no requirement to feel any guilt about your wealth. The most fraught moment I witnessed in three days was an older couple bickering about an artwork one wanted to buy. As they left the booth in question, the husband said to his wife: ‘We came here 20 years ago and I found that Grayson Perry and you wouldn’t let me buy it, so I don’t see why I should let you buy that.”

Any art fair is a marathon of looking, but it’s the listening that often provides the best sense of what’s really going on. It was only 11:39am when I heard the first cork pop at one of several Ruinart champagne carts; behind me, an older woman in a pink fur shawl exclaimed: “Oh, what a relief!” as she made for the open bottle. (I hastily emailed my editor to enquire as to the champagne budget for this article. No response.) Shortly thereafter, I overheard a bevy of young dealers already coordinating the acquisition of a nocturnal pick-me-up. “Let’s keep this plan internal,” one of them said as they went their separate ways.

If there’s business to be done at an art fair, a high proportion of it will be done over the first 48 hours. As an asset class, art is a peculiar thing: it is something nobody needs, bought for the most part by people who can afford not to care. The urge to own an artwork is often coupled with the desire for someone else not to. The groundwork for those hours will start weeks beforehand, when a flurry of pdfs will land in collectors’ inboxes, previewing what galleries will be showing. Last year, I met a London gallerist for lunch in mid-September who told me she had already sent out her Frieze preview. Panicking a little, a week later, having heard nothing back, she wrote again to her collectors offering discounts across the board. Pouncing ensued.

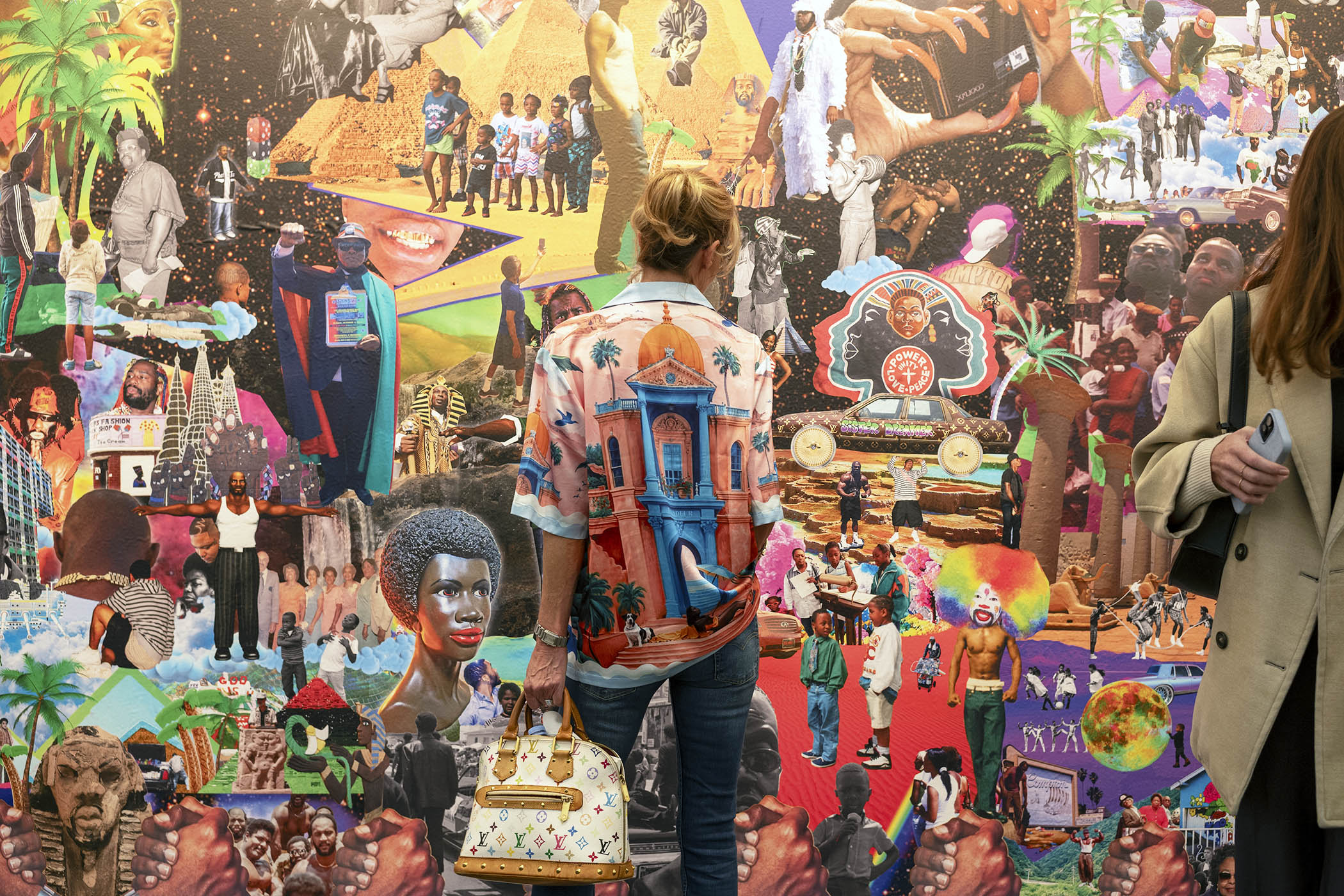

Life imitates art as a Frieze visitor views a colourful work by Lauren Halsey in the Gagosian booth

The first exhibitor I spoke to this year, a pugilistically moustachioed man in a dark navy suit, told me that so far he’d had “lots of nibbles”, but no firm sales. This brand of edgy hopefulness became a leitmotif for the conversations I had with dealers and gallerists. Everyone seemed to be constantly checking in with each other, as if the fair were an arena fraught with micro-aggressions rather than paintings, champagne and 1%-ers.

There were good things to see. On the Approach gallery’s stand, London-based artist Kira Freije’s metal freestanding and wall-based sculptures captured fleeting gestures of frailty and celebration, providing a rare sense of human intimacy amid the hurried impersonality of the fair. On a smaller scale, at JL’s booth, was a work by Gareth Cadwallader that I returned to again and again. A small painting, no larger than a religious icon, showed an androgynous figure, hair obscuring its face, standing next to a round polished table. The figure seemed to be in the act of catching an egg as it rolled off the table’s edge, but it was the view out of the window – a dreamlike tangle of tree trunks and branches – that ensnared my imagination and kept me wanting one more look.

It wasn’t all great. There was a profusion of mirrored works at the fair. At one booth, there were a variety of disco balls, providing an Instagram-ready hall of mirrors. One gallery had brought mirrored modernist furniture and another was showing a distressed-looking mirrored surface with the words “SAINT I AINT” in the typography of the fashion house Yves Saint Laurent. A queue of influencers, iPhones primed, were waiting for their moment. Scattered throughout the fair were mirrored placards imprinted with the words “Reflections of commitment”. These were provided by Deutsche Bank as: “A reflection of art. A mirror of commitment. Together they invite contemplation and celebrate Deutsche Bank’s partnership with Frieze.”

After a couple of hours, when I made it through this looking-glass world to the tent where the bigger, more established galleries were exhibiting, I was already wilting. At one of the Illy coffee carts, I paid £4.95 for a double espresso. (More or less the whole time I was at Frieze, I was drinking an espresso. It cost me a fortune.) Of the world’s true mega galleries (those with premises on more than one continent, such as Gagosian, David Zwirner, Hauser & Wirth, Pace, White Cube), only Jay Jopling of White Cube was present at his gallery’s booth on VIP day.

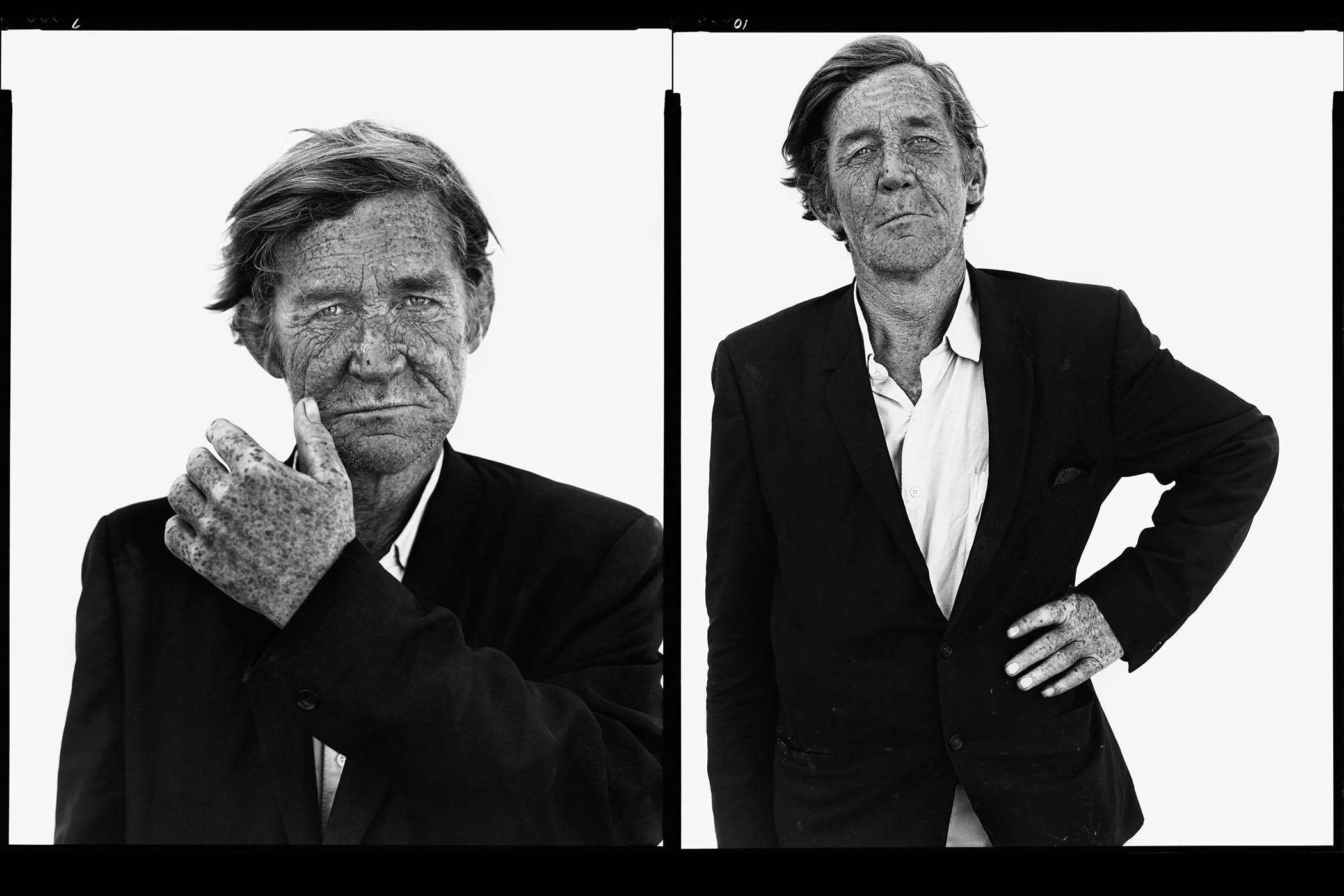

I couldn’t figure out whether his glare was that of a deer in the headlights or of someone scoping out their prey

I couldn’t figure out whether his glare was that of a deer in the headlights or of someone scoping out their prey

Larry Gagosian, the world’s biggest contemporary art dealer, was in London, several people told me, but he loathes fairs. I spied Jopling, who had been Philbrick’s mentor and backer before becoming one of his victims, in his booth’s capacious storage cupboard. He appeared silvery, a trifle Ozempicky, perhaps, as if he were the portrait in the attic to his doppelganger nephew Caspar, who was also working the stand alongside his uncle.

At lunch, I muscled my way into the Gail’s queue and then stood with my sandwich talking to Kimberly Brown, an LA-based art adviser. She told me that market conditions had made things “really hard”. “Everyone is doing less [business],” she said, and every sale seems to require “six times more effort”. Brown also said she thought too few Americans had come to this year’s Frieze, perhaps preferring to go to Art Basel Paris the following week.

One American who was in town was Andre Sakhai, a New York-based collector and art investor who had been a close friend and collaborator of Philbrick’s before, like Jopling, becoming a target of his fraud scheme. I hadn’t seen Sakhai for years, but he’d featured in my book and on the two occasions I saw him around the fair, I couldn’t figure out whether his glare was that of a deer in the headlights or of someone scoping out their prey.

Later in the day, I caught up with another art adviser, this time at the nearby Frieze Masters. If Frieze London can have the energetic feel of a thousand school trips happening in the same place at the same time, then Masters is more akin to the library in a National Trust property: low lighting, hushed conversations, expensively fragrant couples in their sixties peering at illuminated manuscripts. He suggested that the health of a fair could be monitored by close attention to what he called “the Birkin index”: the number of Hermès Birkin handbags (prices ranging from about £10,000 to more than £1m) seen at a fair. The index, he thought, was down.

At least someone was smiling…

The tale of two cities was a running theme. Since long before Frieze held its first fair in London in 2003, there had been an art fair in Paris in October. Until 2021, that fair was Fiac (Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain) but in 2022, Art Basel took over the date. There’s no doubt that Brexit has affected London’s status as European capital of the art trade (in recent years, a number of prestigious London galleries have opened outposts in Paris) and the idea of the French getting the upper hand – the Emily in Paris effect – rankles many of the London dealers I spoke to.

As if to counter this narrative, Sadie Coles, thedoyenne of London’s contemporary art scene, has just opened a new gallery on a townhouse on Savile Row; Stuart Shave’s Modern Art gallery and Maureen Paley’s eponymous gallery are expanding, too. Add into the mix big institutional shows by Peter Doig and Kerry James Marshall, plus commercial gallery shows of market darlings Dana Schutz and Christopher Wool, and it’s clear that London isn’t out of the game just yet.

If commerce and creativity are the ego and super ego of the art world, then its decadent social scene is its unrestrained id. On the eve of the fair, David Zwirner and Victoria Miro galleries had teamed up to give a party at the nightclub Tramp, in the news again that day as the venue where Prince Andrew is alleged to have danced with Virginia Giuffre. (Evidently, Pizza Express in Woking was fully booked.) At the new Chancery Rosewood hotel, in the former US embassy building in Grosvenor Square (rooms from £1,280 a night), two lines of ballgowned violinists serenaded arriving guests and, later, Mark Ronson was on the decks. One dealer lamented that Frieze week parties were so much tamer these days, telling me wistfully about the annual orgies one collector used to host, providing rowed seating for his more voyeuristic guests.

By the time I made it back to the main fair on the opening night post-5pm entry, the aisles had become hazardous with outstretched arms, faces aglow in the cool blue of smartphone screens, eyes anticipating the incoming heart-shaped doses of dopamine. Claudia Schiffer was in town. Leonardo DiCaprio too, his trademark all-black LA Dodgers hat jammed down almost to his eyebrows. On Instagram, the art critic Martin Herbert wrote “Frieze … turns 22 this year. Enjoy Leo being there, guys! Once you turn 25 it’s all over.”

I spied the Turner prize-winning Keith Tyson, husband of Elisabeth Murdoch, wandering the aisles in a powder-blue chalk stripe suit, looking every inch the Tom Wambsgans of the art world. Art has recently become big business for the Murdochs: Tyson’s brother-in-law James owns Lupa Systems, an investment company that has a controlling stake in the parent of Frieze’s main rival, Art Basel.

UBS estimates that the global art market was worth $57.5bn in 2024. While that represents a 12% drop from the previous year, it’s still clear why the Murdochs would want in on the action. Collecting art is one thing; collecting art fairs is quite another. As one artist said to me as I left the fair that evening: “You forget how rich rich people really are, don’t you?”

A couple at the Southern Guild gallery, which featured a sculpture by Zanele Muholi

A few days before Frieze opened, I’d gone to Christie’s to see the artworks that would be up for sale later in the week. I was there that day to see one painting in particular: Self-portrait Fragment (c1956) by Lucian Freud. From an expanse of white canvas and a few charcoal lines, a painting is in the process of emerging; Freud as a young man, his eyes hesitant, his hand touching his cheek as if to confirm that the man looking back at him in the mirror is real, is really him. The work marked a departure for Freud, away from the wide-eyed, delicate portraits he had made previously. But Freud abandoned the painting in the act of its – and his – becoming, as if the reality of his reflection were just too much to bear.

I wanted to speak to someone about the auction houses’ role in Frieze week and sent Charles Stewart, chief executive of Sotheby’s, a message. To my surprise, a few days later, having somehow passed muster with the Sotheby’s PR team, I found myself sitting in a shiny, oak-lined boardroom with him.

The room was hung with blood-red Damien Hirst butterfly paintings that reflected in the glare of the table. Stewart had landed from New York the day before but he had a puppy-dog pep to him. He was bullish about London’s enduring place in the London art world, insisting that “for emerging artists … artists that you’re less likely to be familiar with, I think Frieze is [still] much more interesting ... You feel that energy.”

I have always felt that art fairs are a terrible way to look at art and, especially for young galleries, an unsustainable way to do business: a small booth in the main section of Frieze costs £25,000 plus VAT and another £5,000 for lighting, meaning that on a 50-50 split with your artists, even without shipping and hotels and champagne and coffee, you have to sell more than £60,000 of art just to break even. But Stewart told me he believed in the “convening power … the community, the ecosystem coming together”.

I was curious to hear what he might have to say about the Middle East. I’d spoken to several artists and gallerists who had told me they were disappointed by Frieze’s recent announcement of their first art fair in Abu Dhabi, given the country’s human rights record and prohibition of homosexuality. (Art Basel already runs a fair in Qatar.) When I told Stewart this, he simply said he was confident that people would “vote with their feet” and that “among [Sotheby’s] clientele there is a great interest in travelling to the region”. (Sotheby’s has recently received investment from ADQ, the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund.)

Art is something nobody needs, bought for the most part by people who can afford not to care

Art is something nobody needs, bought for the most part by people who can afford not to care

From his corporate perspective, I could understand Stewart’s reticence to engage with the issue, but later that day, when I’d returned to the fair, a similar sense of caution struck me: this Frieze was the least political I’d ever seen. The fair held booth after booth of bright and cheerful artworks, paintings of the lower halves of cowboys sporting bright red chaps, cabinets filled with pencil drawings of apples, and innumerable vibrant abstract paintings.

It felt like spectacle or entertainment, oddly – and determinedly – disconnected from the fraught times we’re living through. One American dealer I spoke to told me that even established artists have become wary of showing political work from earlier in their careers for fear of commercial reprisal, or cancellation on social media. (The photographer Sally Mann has recently spoken out about censorship and what she called “a new era of culture wars” when photographs by her were seized in a police raid from a museum exhibition in Texas.)

Art, and by extension the art world, should be a site where the unspeakable is said. So at 3:30pm on the Thursday of Frieze, I went along to see the Qatari-American artist Sophia Al-Maria’s advertised performance, Wall-Based Work, an artwork that, the press release said, “takes the form of a comedy act by an artist who has never done standup” and promised an exploration of “the tragic absurdity of late-capitalist cultural production”. By now, this felt just what I needed.

But Al-Maria was late. The show was meant to begin at 3pm but by 3:40pm still nothing had happened. I stood around watching my fellow Friezers, tote bag-toting art students and wealthy older collectors united in tight-lipped politesse until, without warning, a brick-wall backdrop was unfurled and the song Up Against the Wall Motherfucker blared from two speakers. A spokesperson, reading a prepared statement, announced that Al-Maria was on strike and outside the fair, but willing to speak to anyone about her decision not to perform.

When I spoke to her later by phone, she told me that she was striking “in solidarity … not only with the genocide going on in Gaza, but with all of the genocides happening around the world”. She went on to tell me it didn’t feel right to “carry on with business as usual”. It was sort of a relief that someone was willing to say, a la Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener: “I would prefer not to.”

Related articles:

The art world isn’t the art market, but they are symbiotically linked: sometimes, art is the dominant force; at other times, the market prevails. All art doesn’t need to be politically engaged, but it felt like a collective dereliction that this year’s Frieze was quite so apathetic.

The market may well be difficult just now, but it may also be smoothing the edges of what art can be.

My final trip to the fair was on Friday lunchtime. The frenetic atmosphere of the previous two days had dissipated. Champagne had been replaced by nozeco, and green juices were abundant; a diet of booze, espresso, nicotine and cortisol had taken its toll. The tent felt like being inside a day-old balloon, the air damp and slightly sour, like morning breath. For some, there were still two more days of this.

Before the fair, dealers had been fearful of a commercial bloodbath, but that hadn’t materialised. According to Frieze’s post-fair press release, 90,000 people from 108 countries visited. (This included, but was not limited to, Madonna and Mick Jagger.) Sales were stronger than expected, too, with Gagosian selling out its booth of Lauren Halsey works, Hauser & Wirth selling a Magritte for $1.6m. Smaller galleries also reported healthy sales: Soft Opening sold 12 works by artist Ebun Sodipo and the Pit sold out its entire booth. I wandered up and down the aisles. At one gallery, where a video camera purported to show two people living inside the sealed walls of the booth for the duration of the fair, a very wealthy young couple were in conversation with the gallerist. After they filmed through the viewfinder of the camera with their phones, the couple asked if the artists behind the wall could hear their conversation? “No,” the gallerist answered, “but they can hear our footsteps.” At that, the young woman jumped up and down maniacally, stamping her feet and giggling like a child

I had a sense I’d seen enough. As I made for the exit, I recalled that, when I accepted the commission to write this piece, I had decided that it would be my last about the art world, at least for a good while. On the bus home, I swiped through the many photos I’d taken in the past week. When I came to the Freud self-portrait, I paused. Freud painted many more self-portraits over the next 50 years of his career but if Self-portrait Fragment told me anything, it was that it’s always OK to call time on something. I’m not finished with the art world – I may never be – but sometimes putting down the paintbrush is the only thing to do.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photographs by Matt Stuart