In many people of Nigerian parentage – specifically, in my case, of the Ikwerre ethnic tribe of the River State in its south-west regions – there remains a craving for a shared history, one that might bridge the tribal divisions that were a legacy of British colonial rule and civil war.

That is one of the ambitions of Tate Modern’s Nigerian Modernism: Art and Independence, the first major UK exhibition to explore the influence of modernist art in Nigeria. Given the current period of political amnesia in Britain about national identity and colonial legacy, it could not be timelier. But for the exhibition’s curator, the British-Ghanaian Osei Bonsu, who joined Tate six years ago, Nigerian Modernism’s motivations run deeper. “It’s a show that’s been a long time coming,” he said. “When Tate Modern opened in 2000, we had an extraordinary inaugural exhibition called Century City that was looking at the various sites of artistic modernism globally, but now we more often associate [the gallery] with the development of European modernism. So the exhibition grew out of a desire to realise the ambitions of Tate’s [original] commitment to global modernities that are more often associated with pan-Africanism and independence.”

What sets Nigerian Modernism apart from similar exhibitions is a distinctive narrative arc that transcends the moment of independence. While it is true that freedom from colonial rule inspired a group of artists to capture the newfound national optimism, the show emphasises how modernist sensibilities were already at work within colonised Nigeria: for example, in the collection of images of traditional Nigerian rulers and chiefs by Jonathan Adagogo Green, one of Africa’s first photographers, or the work of the pioneering painter and teacher Aina Onabolu, who reformed Nigerian education, introducing the teaching of African art forms.

Aina Onabolu’s Portrait of an African Man 1955. Main image above: Ben Enwonwu’s The Durbar of Eid-ul-Fitr, Kano, Nigeria 1955

Throughout the exhibition, there is an inherently flexible idea of modernity; from the 1940s onwards, Nigerian artists were grappling not only with questions of national and self identity, but also the development of different artistic languages and cultures. The question of what it means to be Nigerian drives the exhibition.

The show captures a Nigerian society that is both resolutely forward-looking, and devoted to old ritual and spiritual practices. Two rooms introduce us to the Sacred Art Movement and Osogbo Art School, which produced artworks deeply rooted in Yoruba cultural traditions, offering a version of modernity that was guided by themes of ceremonialism, tribalism and religiosity. These contrasts are framed most prominently in the work of the painter and sculptor Ben Enwonwu, arguably Africa’s most acclaimed visual artist of the last century. Trained at UCL’s Slade School, Enwonwu’s life and work navigated the polarising relationship between Nigeria and its coloniser: there was his bronze sculpture of a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II that drew praise from the monarch and suggestions elsewhere that he had “Africanised” her features; the “Daily Mirror” sculptures, comprising seven ebony figures each holding a newspaper commissioned in 1960 to sit on the forecourt of the Mirror’s new central London headquarters; and his Negritude collection, a series of silhouetted watercolour paintings of dancing women, which sought to celebrate Nigerian aesthetics and beauty.

Ben Enwonwu (centre) and his ebony sculptures commissioned by the Daily Mirror in 1960

Bonsu agrees that there is something particular about Nigerian modernity, largely because of the influence of the country’s diaspora both pre and post-independence, who found their homes across Europe and beyond. “Nineteenth-century Nigeria is already a multinational environment,” he said, “filled with kingdoms whose foundations are rooted in exchange with the Portuguese, with the British and with other groups. That kind of rich sense of cultural hybridity is there even before modern art begins.”

Some of the mixing of traditions was abrupt. In a section dedicated to the exploration of a post-independence Lagos, images show stunning modernist architecture from the 1960s that is so distinct in style it feels as though we’ve skipped a time period. But it equally offers an extraordinary example of the drama of Nigeria embracing elements of European modernism, while infusing it with its own artistic language.

In this context, artists such as Uzo Egonu – who lived all his adult life in London and merged Igbo and European styles – emerge as outstanding figures within a canon of British and Nigerian modernity. His figurative paintings, such as Woman in Grief and Woman Reading, explored the struggles of a new Nigeria from Britain, with some of his most expressive work produced after losing much of his sight, a period he called “painting in darkness”.

Related articles:

‘Heavily invested in the impact of war and independence’: Uzo Egonu, Stateless People; an artist with beret, 1981

“What we need in the context of historicising African art is not just a temptation to reach into an ancient past,” says Bonsu. “What I thought was fascinating about looking at artists in the 1960s, for instance in Lagos and in Zaria, is that they saw themselves as being in dialogue with Nok Terracotta sculptures or the bronzes of Benin [as well as European modernist thinking]. And they were constantly looking for ways to amalgamate and synthesise those traditions. I think artists are still doing that today.”

This shift in curatorial focus from race and continent to the specifics of ethnicity and nationhood suggests a new Nigerian diasporic art movement. My Father’s Shadow, the BBC/BFI produced film, by the British-Nigerian film-maker and visual artist Akinola Davies Jr, is a moving and subliminal story of a father and his two sons journeying through Lagos against the backdrop of the tumultuous 1993 Nigerian presidential elections. The first Nigerian feature film to be picked for the Cannes official selection, its engagement with Nigerian cultural and spiritual memory underpins the film’s excitement ahead of its UK cinema release on 6 February 2026.

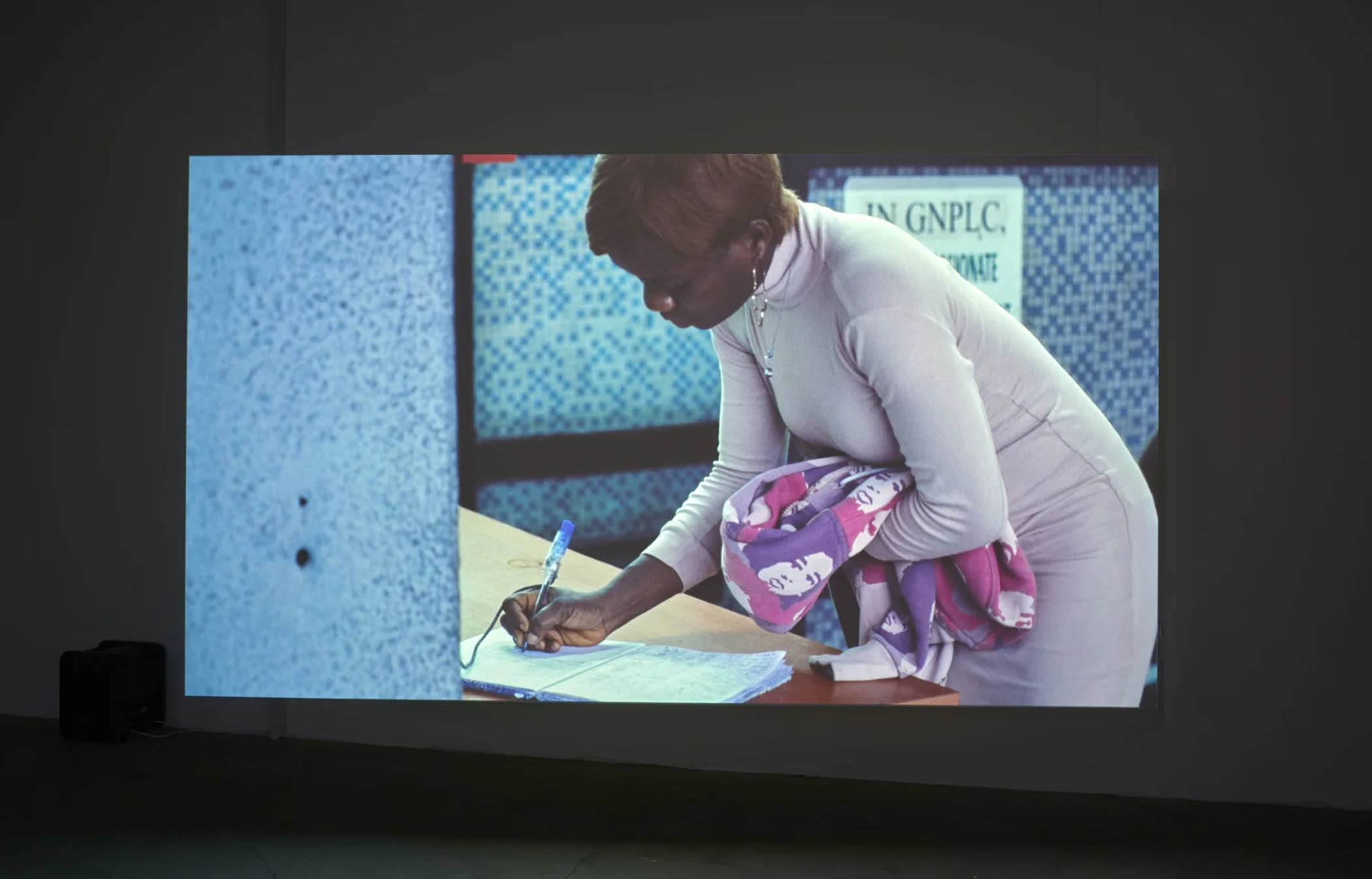

Meanwhile, Tendered, the artist Karimah Ashadu’s first institutional solo show in the UK opened at the Camden Art Centre last week. Winner of the Silver Lion for Promising Young Artist at the Venice biennale 2024, she captures the contours of Lagosian hyper-masculinity, labour and socio-economic hardship in her films Cowboy and her new commission Muscle.

Karimah Ashadu’s film Cowboy, exploring masculinity in Nigeria

Other artists engage with how this culture plays out within the historical dimensions of immigration, urbanism and housing. Adeyemi Michael and Ayo Akingbade, two prominent British-Nigerian visual artists, are concerned with the relationship between the Nigerian diaspora and the homeland; most recently, Akingbade’s Faluyi (2022) takes a more introspective approach to her own Nigerian spiritual ancestry. The Peckham-born film-maker and visual artist Jenn Nkiru– whose forthcoming film, The Great North, was the centrepiece of a stunning career retrospective at SXSW earlier this year – has directed music videos for artists such as Beyoncé and Kamasi Washington, which infuse American popular visual culture with discernibly Nigerian surrealist textures.

Collectively, we might start to sense a group of visual artists whose work speaks to and draws from Nigerian diasporic experiences and connects directly to the homeland of Nigeria. The importance of Nigerian Modernism is that it gives that group a reference point in the quiet confidence and self-assuredness of work from the last century. There remains a powerful value in viewing disparate Nigerian artworks from the country’s 250 separate ethnic groups within a single space. In the penultimate room, we are met by a haunting audio reading of the poem Come Thunder by Christopher Okigbo, who died in 1967 while fighting for Biafra against Nigerian forces. It provides a deeply effective extra layer of meaning to the work of Uzo Egonu, whose paintings in the final room, Stateless People, were heavily invested in the impact of war and independence from his position as a diasporic subject in Britain.

Ayo Akingbade’s The Fist, 2022

This all suggests fertile artistic conditions for a new Nigerian diasporic wave to develop. Bonsu recognises this potential, albeit with qualifications. “I would say there is a wave, but we absolutely have to also say it’s a continuum. What’s fascinating is a lot of the most productive periods came about when [different groups] were sharing knowledge, sharing skills, sharing creative ideas. And there was this real sense of a creative wellspring – one of abundance. I think now with various challenges that artists are facing, not only with the cost of living but with global challenges around arts education, it’s quite hard for artists to feel part of a community. I hope this show can engender and inspire a sense of collective creativity that shows that through collectivity artists are able to sustain difference.”

Nigerian Modernism is at Tate Modern until 10 May 2026

Photographs by Ben Enwonwu Foundation/Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art, Pan-Atlantic University/The estate of Uzo Egonu. Private Collection/Karimah Ashadu/Ayo Akingbade

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy