Photographs by Jillian Edelstein

Jillian Edelstein grew up in apartheid-era South Africa, where her whiteness, she once said, granted her “massive and instant privilege”. While working as a social worker in the late 1970s, she began to take photographs in Cape Town’s District 6 neighbourhood, which the authorities were in the process of demolishing. In 1980, she became a press photographer, covering social and sporting events but also bearing witness to protests, unrest and police repression. Photography, she later admitted, was a way to channel her “complicated emotions – among them anger and guilt”.

Having left South Africa in 1985 to study photography in London, she watched from afar as her homeland underwent seismic social and political changes, including the end of apartheid in 1991 and its first democratic elections in 1994. On a visit to South Africa for a family wedding in 1996, Edelstein was transfixed by the television footage of the nascent Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a restorative justice process chaired by the celebrated Anglican bishop and human rights’ campaigner Desmond Tutu.

Joyce Seipei with Jerry Richardson, the man who murdered her son

By then she was an in-demand editorial photographer and, having been commissioned by the New York Times to photograph Nelson Mandela, she ended up spending five months in Cape Town making portraits of the victims and perpetrators of apartheid, as well as those involved in internecine violence. Almost 30 years later, a selection of the portraits feature in an exhibition entitled Truth and Lies at the North Wall arts centre as part of the Photo Oxford festival. Against the backdrop of anxiety and anger that increasingly defines our suddenly fragile-seeming political culture, Edelstein’s pictures have assumed an added resonance. The central question they ask is, can you combine justice with forgiveness? It is a question that echoes through other recent conflicts, from Northern Ireland to the Balkans, and will one day hang over attempts at a solution to the Israel-Palestine question.

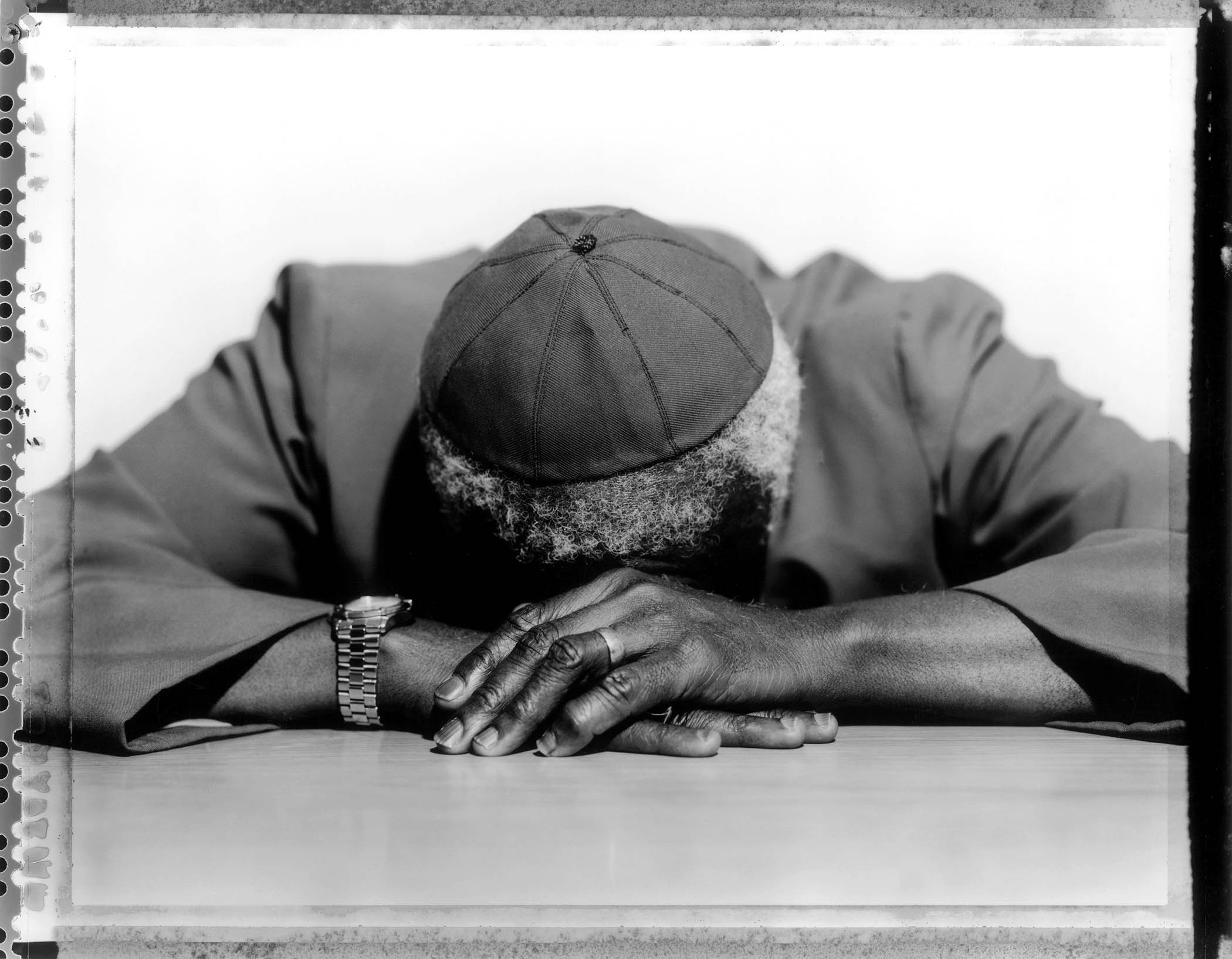

In 1996, against a heightened backdrop of emotional testimony, raw confessionalism and attempts at self-exculpation, Edelstein decided to take pictures outside the hearings, creating a makeshift studio in which a white backdrop remained a stark constant. The sense of detachment the camera afforded her was crucial, even if she later recalled how she trembled while photographing five policemen who had confessed to committing 41 murders in the 1980s.

The Anglican bishop and human rights’ campaigner Desmond Tutu, who chaired the hearings

In another loaded portrait, Joyce Seipei stands next to Jerry Richardson, the murderer of her son, Stompie Seipei. In the hearing, she had heard how Stompie had been taken to Winnie Mandela’s house on 29 December 1988, before the killing. Months later his decomposing body had been recovered from a river. Joyce had identified him from his white hat and running shoes.

Edelstein recorded the moment she and Joyce met in the diary she kept throughout the proceedings. “Just before Joyce arrives, Jerry Richardson, handcuffed and wearing a strange Barbie badge, appears. He wants to be photographed with Mrs Seipei. She agrees. A strange silence accompanies the picture-taking. Richardson says the small football he carries is his good luck charm.”

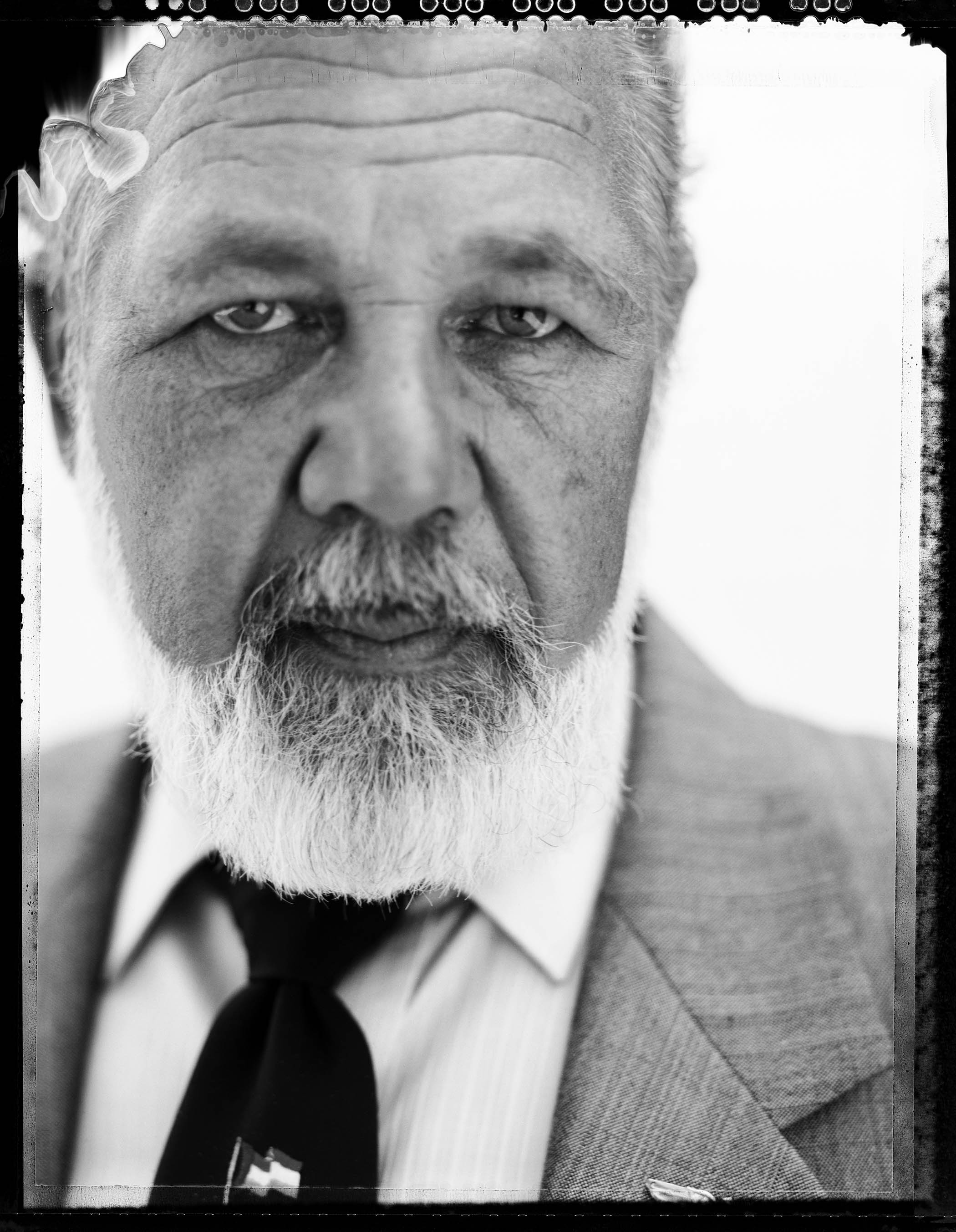

Eugène Terre’Blanche, leader of the far-right Afrikaner Resistance Movement, applied for amnesty for acts of political thuggery

The resulting portrait hums with a sense of uncomfortable uncertainty and, as such, is a kind of distillation of the heightened drama of the hearings.

Related articles:

One unanswered question resounds throughout the series: why did the perpetrators agree to be photographed? And, in this particular instance, one also wonders why Richardson wanted to be photographed with the mother of a boy he had killed? For some critics of the process, the public hearings allowed the perpetrators to indulge in a theatre of performative contrition, while also offering amnesty to those who should have faced justice for their crimes.

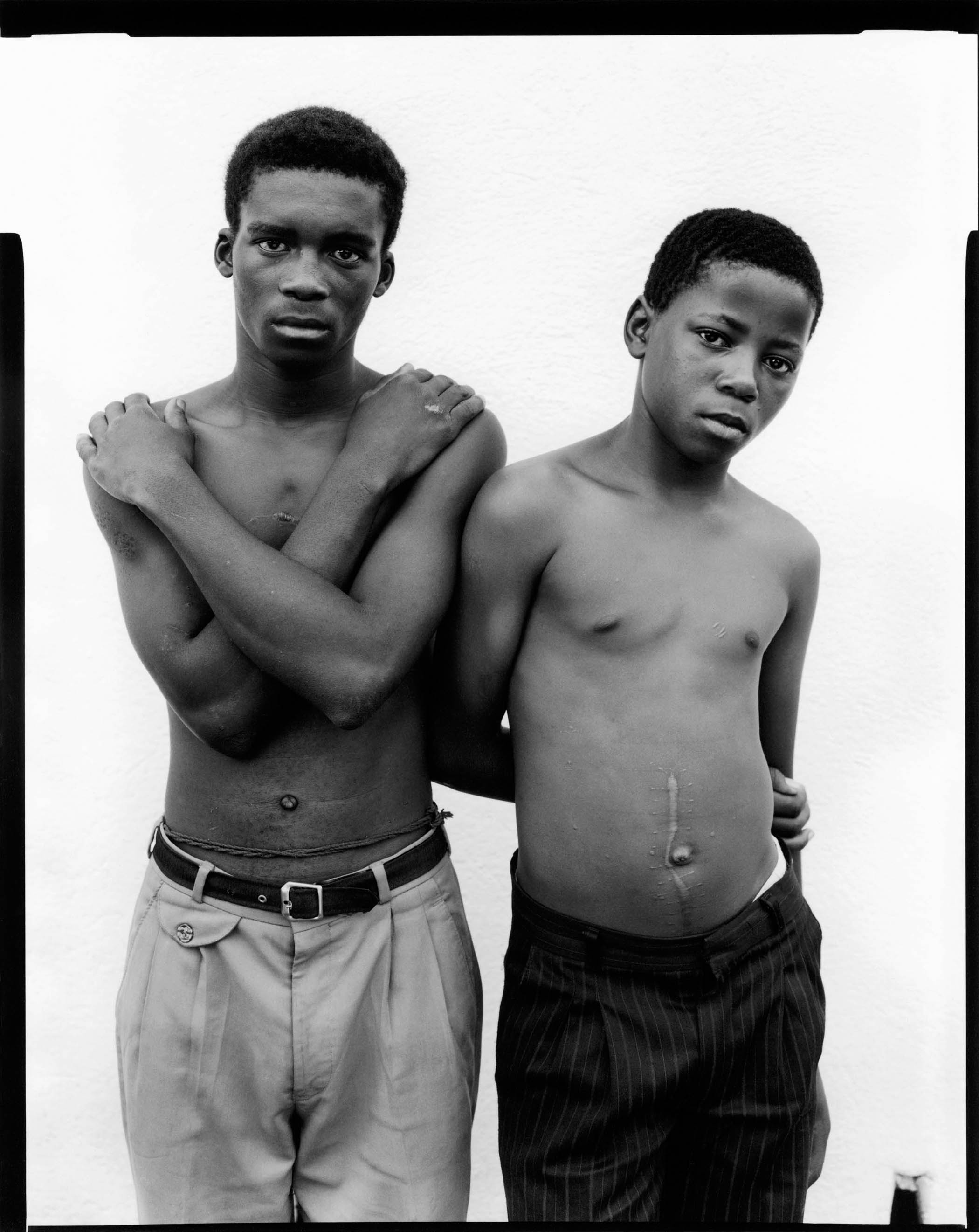

Thembinkosi Tshabe, 19, and Mxolisi Goboza, 15, described to the hearings how they had been shot and wounded by police during a demonstration

As if in acknowledgment of these contradictions, Edelstein’s pointedly titled her series Truth and Lies. The resulting portraits are now a historical record of a pivotal, but still contested, moment in South Africa’s troubled history. For the victims of that time, uncovering the truth was crucially important, but it could never be enough.

“In general, the success of this long-term project in South Africa’s history remains questionable,” Edelstein later concluded. “But it is hard to think that for many individuals it has not been invaluable. Joyce Mtimkulu, who discovered that her son, Siphiwo, had been shot and detained, poisoned by the security police, released, kidnapped again and finally killed, seemed to speak for many when she told me, after listening to the testimonies of those responsible: ‘At least now we know what happened.’”

Policeman Gideon Nieuwoudt, left, was implicated in the murder of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko, and Mike Barnardo, a member of a witness protection team

Area for non-contact visits at Robben Island prison

Father Michael Lapsley lost an eye and both hands to a letter bomb

Joyce Mtimkulu holding hair that once belonged to her murdered son, Siphiwo

Truth and Lies runs at the North Wall arts centre in Oxford until 9 November