Richard Avedon’s photographs of drifters, miners, waitresses and day labourers in the American west, taken over five years in burning monochrome, were a sensation when first shown in Texas in 1985. They have remained famous – or notorious – ever since. The celebrity photographer of sad Marilyn and scarred Andy, of wide-eyed Oppenheimer and topless Capote, as glamorous as the couture labels he shot for Vogue, had turned his expensive lens on the common man. Avedon was praised for his humility.

From the thousands of images exposed, the photographer chose 126, blown up so vast they filled the immense windows of the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth. An installation shot, taken from the street by night, shows the figures like Easter Island statues through the glass. The show toured, visitors queued across the States; the publicity was so expansive it received its own criticism. These portraits were archetypes, documents of living history, the west personified, perhaps even the truth of life revealed; unless they were further exercises in style?

Perhaps because they cannot mean the same thing to us as to an American audience, Avedon’s images have never been shown here in their entirety. But 21 are currently on display at Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill and the experience is a revelation. The size of billboards, insistently frontal, intensely graphic in their saturated black and white, these images are so detailed in terms of freckles, moles and scars, the missing tooth in mouth or zip, the sun-bleached hairs on a forearm or the diesel stain on worn jeans, as to overwhelm the mind and eye. If it weren’t for their glossy perfection, prophylactically sealed against question or doubt, we would be like Gulliver in Brobdingnag, exploring a land of giants.

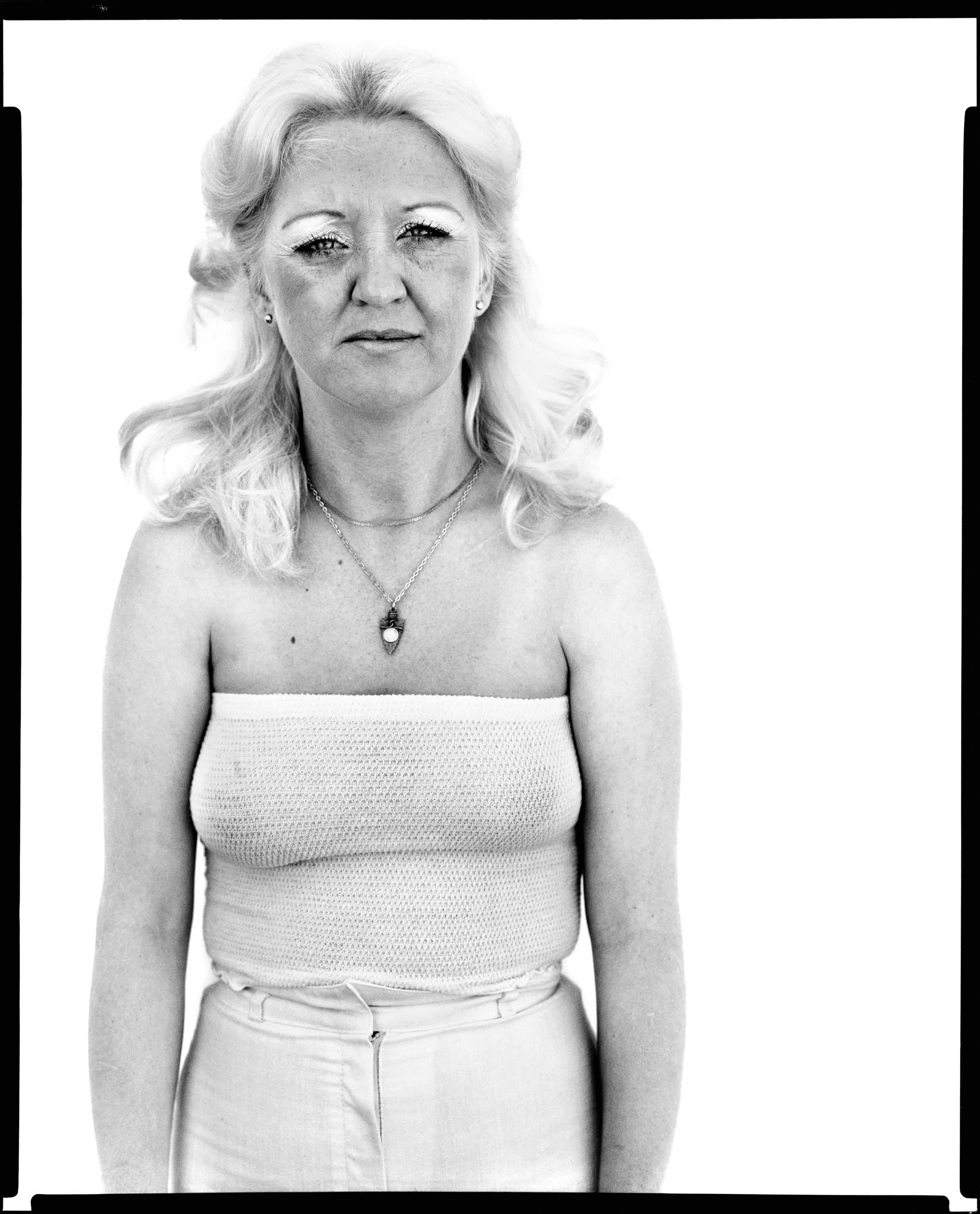

Carol Crittendon, bartender, Butte, Montana, 1 July, 1981

Roger Tims, Jim Duncan, Leonard Markley, Don Belak, coal miners, Reliance, Wyoming, August 29, 1979

Carol, a Montana bartender, wears a strapless top too thin to conceal her breasts but thick metallic eyeshadow beneath the pencilled crescents of her brows. One eye is noticeably lower than the other (Avedon is said to have been both friend and rival to Diane Arbus, her camera so focused on human irregularity) as she stares inexpressively back at the lens. Her hands are as concealed as her character.

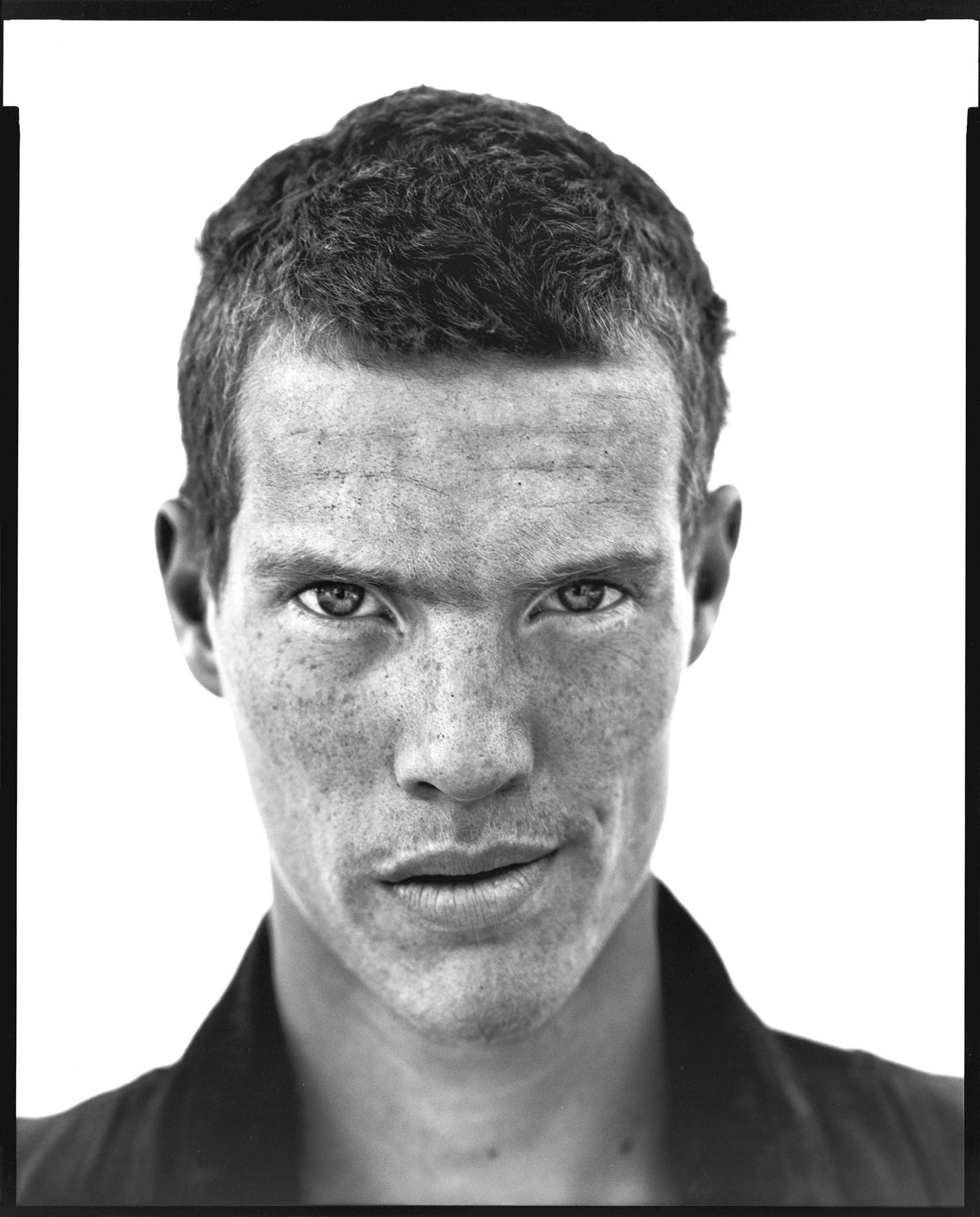

Robert is an unemployed meat packer, young and lean with a buzz-cut and what might be dazzling blue eyes, though you never can tell. Why is he out of work in Colorado, and why do we see only his enormous face? Alfred, an elderly dryland farmer in North Dakota, has lost an arm. His trousers are not quite buttoned. Does he know, has he allowed this? One sleeve hangs empty. Did he lose his arm to the land?

Insistently frontal, intensely graphic, these images are so detailed in terms of freckles, moles and scars, the missing tooth in mouth or zip, as to overwhelm

Insistently frontal, intensely graphic, these images are so detailed in terms of freckles, moles and scars, the missing tooth in mouth or zip, as to overwhelm

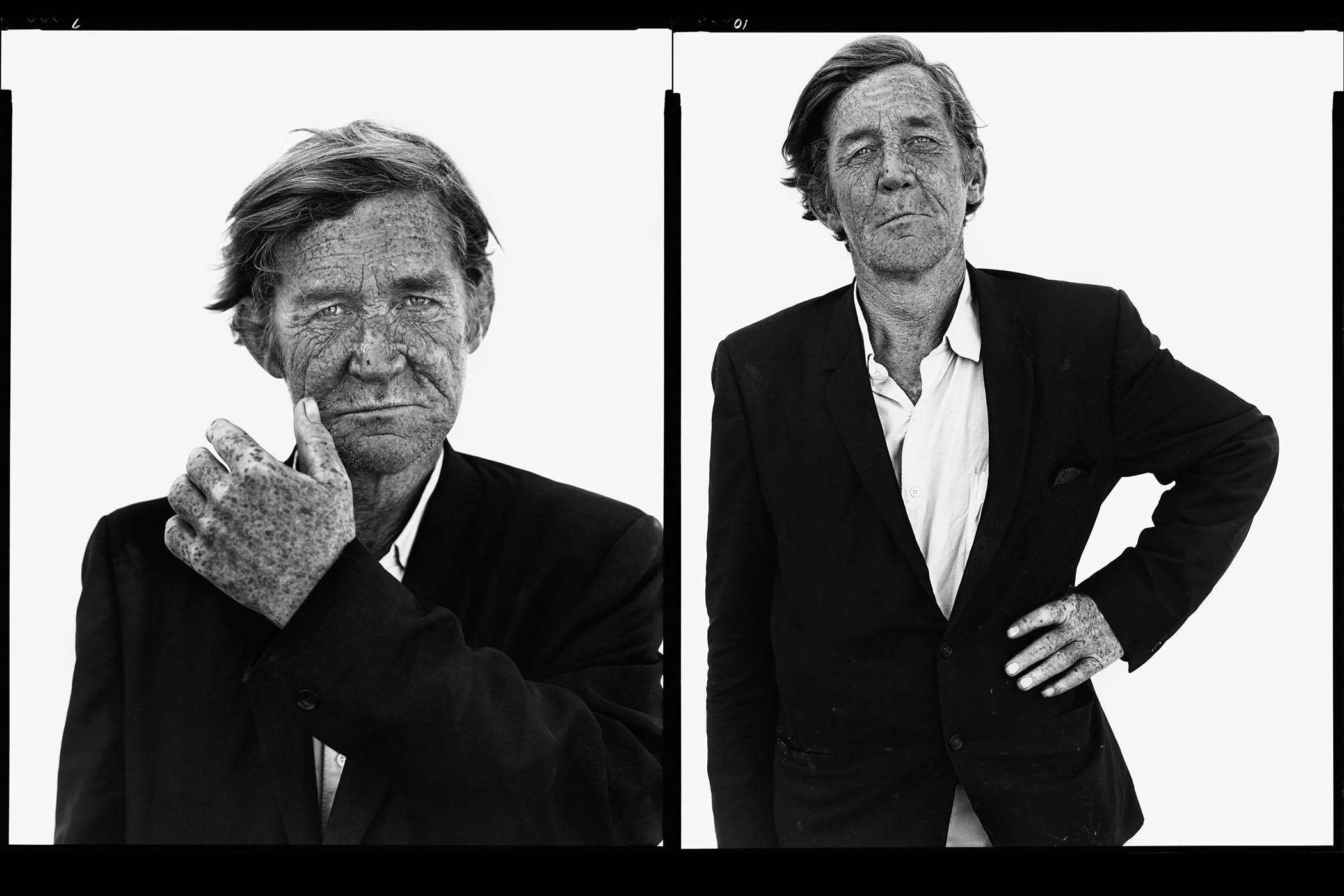

The hunched dark shapes of miners in copper, coal and uranium loom high across the gallery, blackened by the filth of their underground labours. Baked dirt turns one into a terracotta warrior, others into grimy hieroglyphs. Four miners are divided into a massive triptych, the faces of two men split and mismatched by the process. Nothing in the portrait, or Avedon’s unvarying aesthetic, explains why.

For these westerners – poor, afflicted, overworked or jobless – are all extracted from their context. Each is photographed against a stark white backdrop, taken out of time, life and place. They have no attributes, like the bricklayers and farmhands in August Sander’s marvellously humane images of his fellow Germans. They have no power of expression, or movement or speech.

Robert Dixon, meat packer, Aurora, Colorado, June 15, 1983

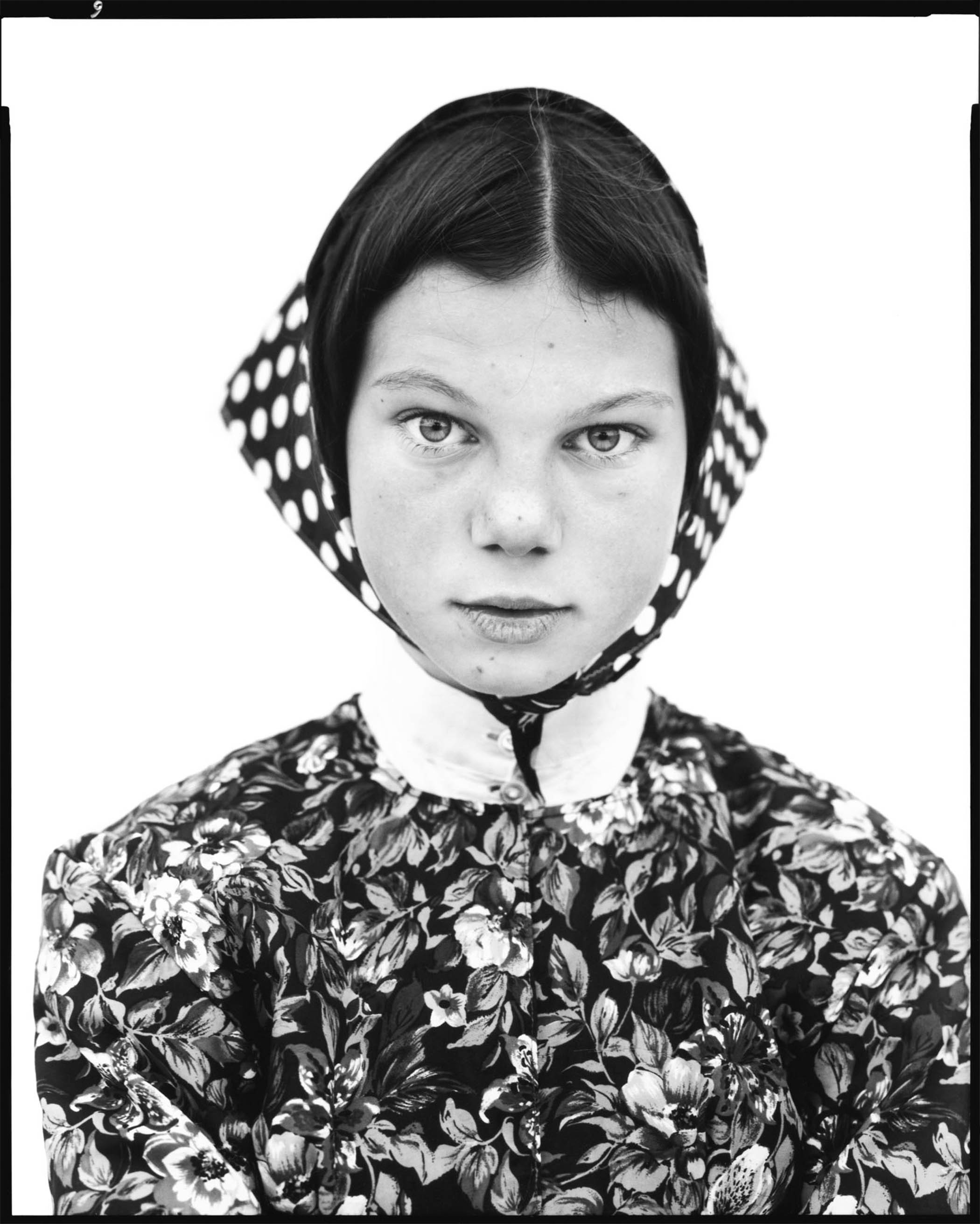

Freida Kleinsasser, 13, Hutterite colony, Harlowton, Montana, June 23, 1983

This might succeed where the subject is known to the world – Reagan, Giacometti, Beckett, all isolated in the same bare and shallow space. Although even then, the inner being can appear shockingly occluded. “My photographs don’t go below the surface,” Avedon said, “they’re readings of what’s on the surface.” Nothing more, if certainly nothing less: this is his limitation.

Related articles:

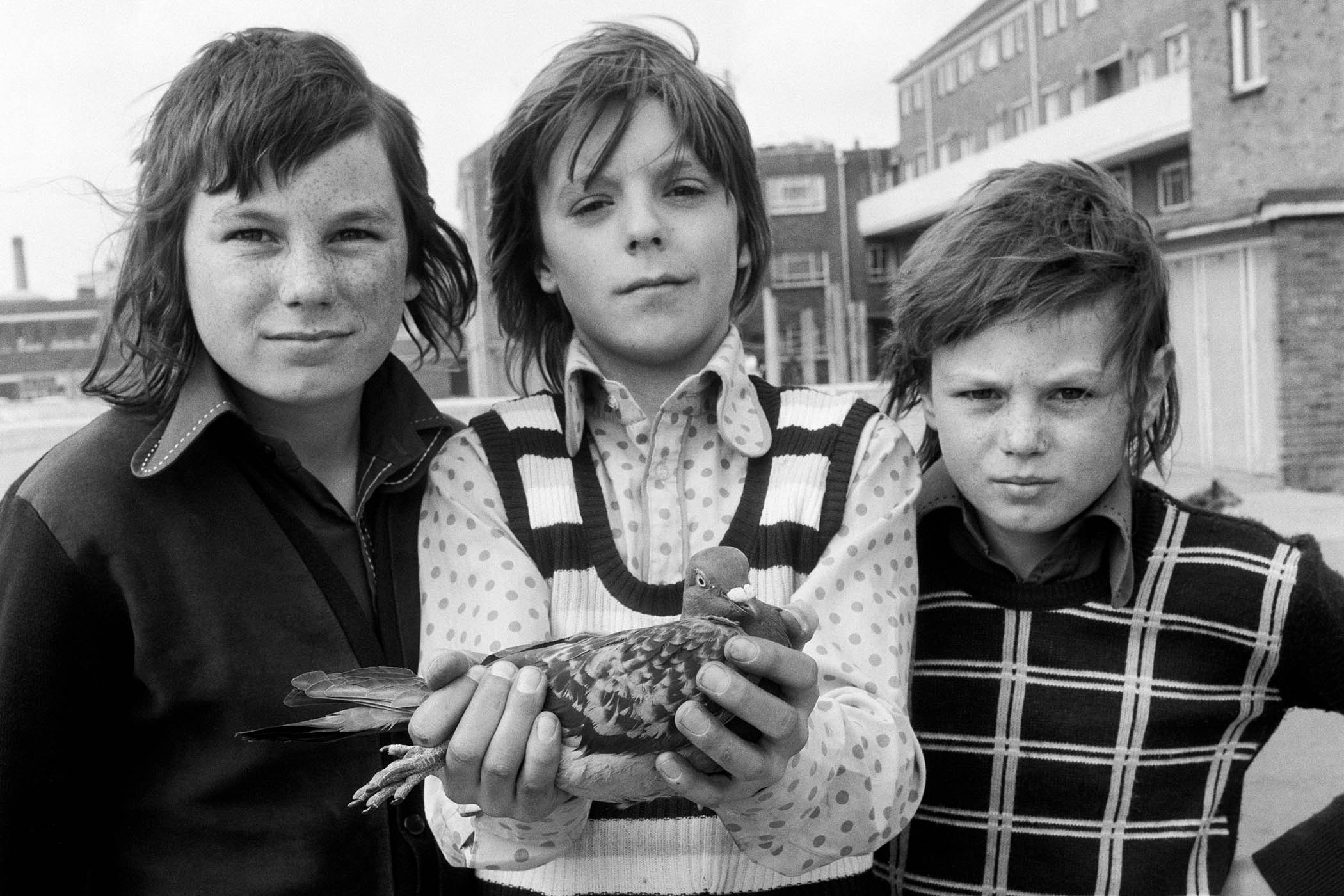

An exceptional aspect of the Gagosian show, however, is the narrative set up by including the off-duty polaroids of each shoot taken by the artist or his assistants for reference. These are displayed in a grid by the entrance. From this you learn that the armless farmer is tiny, that the bartender has a distinct sense of humour, that the motel janitor and maid are so young and tense they never break the pose even for the polaroid.

The drifter who looks so incredibly suave in his black jacket, posing for all the world as though on a Vogue cover shoot, has a mirthful defiance even in this casual downtime. Surely he is a free spirit, immune to Avedon’s instructions. The sharpest contrast is the little Hutterite girl, shyly receding into the shadows off stage, clear-eyed and obedient in the massive portrait. Her image is too enormous to be viewed up close. You have to back off just to see it.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

No black subjects were chosen for In the American West and the women have an oddly narrow range of roles – housewife, barmaid, the occasional trucker. Avedon photographs three sisters who run the Loretta Lynn fan club for their big hair and identical makeup, it seems, not for their mutual occupation. And Petra’s experience as a factory worker in El Paso is sidelined, despite this description of her occupation beneath her picture. Avedon has her pose with a sheaf of dollar bills on her birthday: she is as uneasy in the polaroid as in the formal portrait. His unyielding style meets her passive resistance.

This is photography as installation art: all these fierce figures against dazzling white voids, all this graphic zip and register looming around you. These are pictures before they are people. By depriving these westerners of their place and personality, Avedon diminishes them even as they are magnified to a scale beyond apprehension. Sacrificed to the imperative of style, they are larger than life and yet so much smaller.

Richard Avedon: Facing West is at Gagosian, London, until 14 March

All photographs by Richard Avedon © The Richard Avedon Foundation, courtesy of Gagosian