The year ahead is a momentous one. For the first time in living memory, almost every British museum is showing art by women. The art industry moves with battleship slowness, no matter that it loves to appear burningly current. Exhibitions can be years in the making. But gradually, very gradually, then all of a sudden: this is the year of the woman.

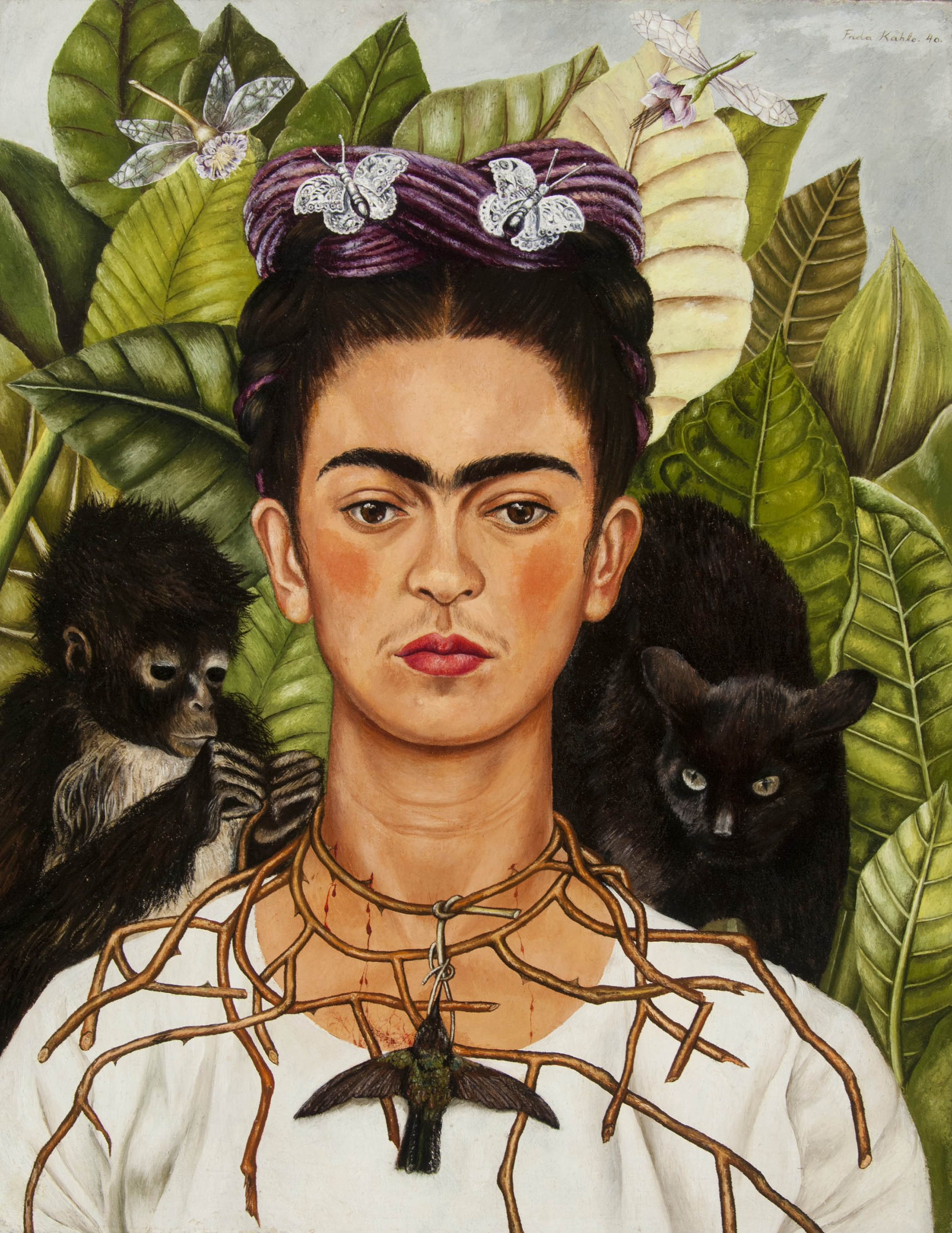

Tate Modern leads with its Frida Kahlo blockbuster in June: all the self-portraits and more. The elusive genius of Cuban exile Ana Mendieta gets an overdue retrospective in July, including the famous Silueta Series in which she left her imprint on the American landscape. Booking has already opened for Tracey Emin in February. If you’ve never seen the bed, the blankets or the miserabilist monoprints, now is your chance.

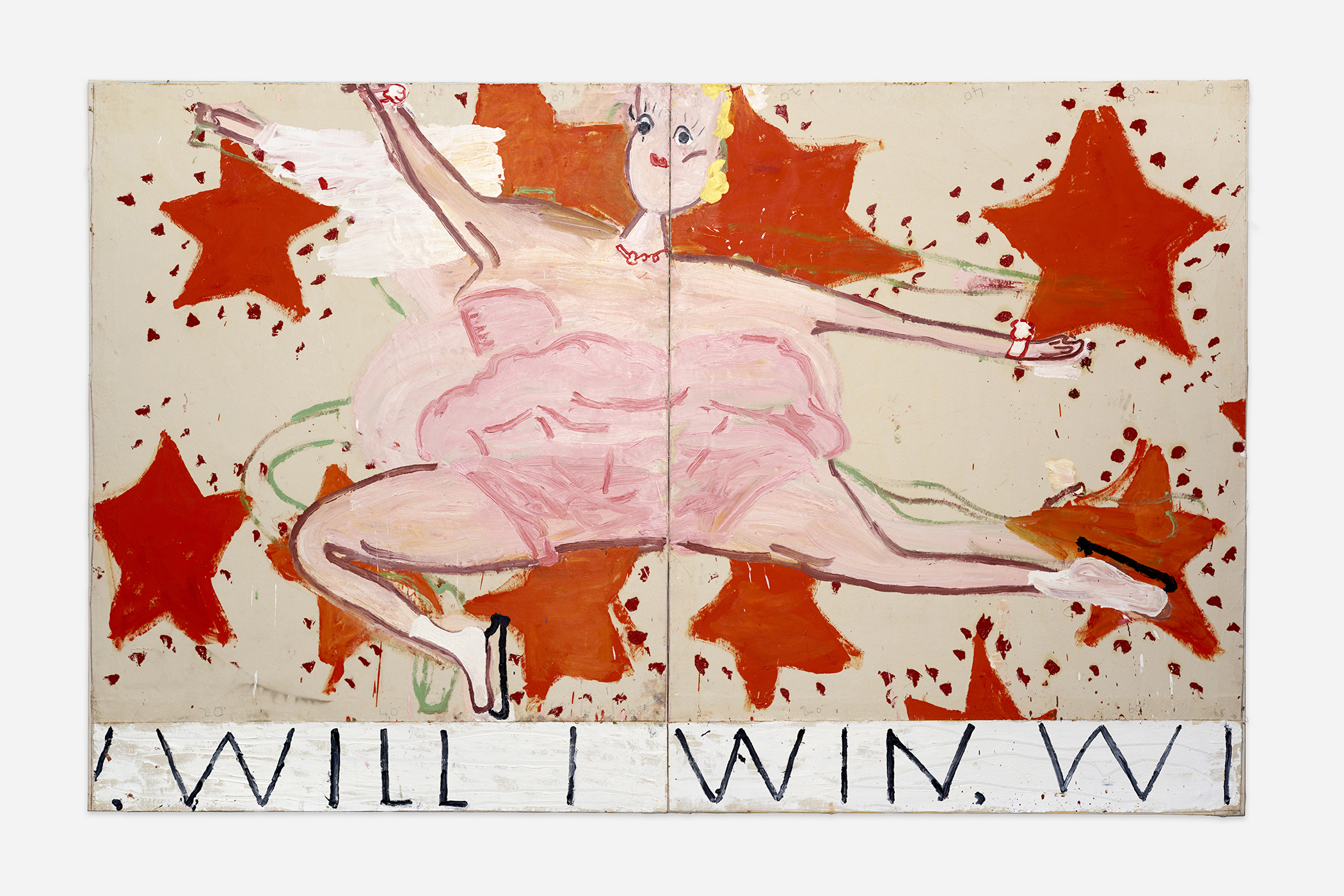

The same month, the main galleries of the Royal Academy are, belatedly, given to the grand and gleefully ungainly paintings of Rose Wylie. Also opening in February is the Colombian pop painter Beatriz González, whose fizzing pictures will fill the Barbican Art Gallery. Both artists are now in their 90s.

Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940. Main image: The Locked Room, 2016 by Chiharu Shiota

After her recent sell-out Grand Palais show, Japanese sculptor and installation artist Chiharu Shiota has her first big British survey, floor to ceiling, in what promises to be a fiery experience at the Hayward. Cecily Brown’s densely teeming paintings, equally chic, are at the Serpentine South from March (opposite David Hockney, no less, at the Serpentine North).

Spring also brings sculpture shows by the Turner prize winner Veronica Ryan at the Whitechapel and the Spanish artist Angela de la Cruz at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham. Zineb Sedira, runaway hit of the 2022 Venice Biennale with her Parisian bar-cum-1950s film set, takes over the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain. I doubt many artists today are better able to transform those inhospitable marble halls into a living enchantment.

The Venice Biennale, incidentally, takes place in May 2026. After much turmoil, the self-trained and surprisingly anodyne sculptor Alma Allen has been announced as “Trump’s choice” for the US pavilion, to the dismay of American critics. Turner prize-winning artist Lubaina Himid is representing Britain.

Marilyn Monroe, Elsa Schiaparelli and Queen Elizabeth II all become stars of their own shows in 2026, with celebrations of their style, influence and appearance at the National Portrait Gallery, Victoria and Albert Museum and the King’s Gallery respectively. Marilyn and Elizabeth would both have been 100 this year, and 2026 sees the 150th anniversary of the painter Gwen John’s birth. An unmissable retrospective of her luminous, introspective and quietist works starts in February at the National Museum Cardiff, in her native country, and tours to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh from August.

Pink Skater (Will I Win, Will I Win), 2015 by Rose Wylie

The documentary photographs of Tish Murtha, in all their hard and truthful beauty, are being shown at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead from July. And this is a golden year for photography. Dulwich Picture Gallery unites Diane Arbus, Berenice Abbott, Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, among others, in Portrait of a City: A Century of American Photography in late July. MK Gallery in Milton Keynes has Jacques Henri Lartigue’s street photography in June. Tate Britain has the 1990s in the photography of Juergen Teller, Corinne Day and Nick Knight, alongside the YBAs. The most transfixing of these commemorations will surely be Tate Modern’s Light and Magic, in October, celebrating the birth of art photography from the 1880s on.

Two epochal events take place at the National Gallery in 2026. There has never been a UK show devoted to the dark and glittering art of Francisco de Zurbarán, not least as so few museums are prepared to part with the mysterious saints and hauntingly beautiful still lifes of this 17th-century Spanish master. Nearly 50 paintings will be on display – a stupendous concentration of power in one museum. And all the revolutionary portraits of Jan Van Eyck will be united for the first time in late November: the new face of portraiture in the new medium of oil paint.

Three spectacular exhibitions will doubtless book out fast. Whistler, at Tate Britain from May, presents the US radical as a global figure, pioneering new techniques, painting ethereal nocturnes and exquisite yet astute visions of modern life. Renoir and Love, at the National Gallery from October, will be all flirtation, dancing and seduction. And Painting the French Riviera, at the Royal Academy in the same month, brings the azure skies and heat of St Tropez and Nice to grey London in the art of Bonnard, Matisse and Cézanne.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

But for me, in this tide-turning year, the woman who has waited longest for due acclaim remains the Scottish artist Joan Eardley (1921-63), a landscape painter of stirring genius and one of the most original artists of the 20th century. Her paintings are being shown alongside those of Constable and Monet at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art from April onwards: a true radical, a great visionary, a painter of equal force.

Photographs by DACS/Jari Lager/Nickolas Muray Collection of Mexican Art