William Nicholson (1872-1949) wore patent leather pumps and spotless white trousers at the easel. He liked fancy shirts, silver teapots and Staffordshire vases, a clubbable dandy as much at home in Bloomsbury as Paris or Drury Lane. He is said to have been entertaining company and the garrulous flow of paintings and prints that won him a knighthood have that quality too: pleasing, sociable, fluently self-aware. But what else?

The famous works, fully present in this vast survey, are almost all graphic in essence. That is literally true of the brilliant woodcuts: the whiskered cricketer batting slowly on a Sunday; the guardsman on his high horse, undermined by the foolish stricture of his chinstrap; the fashion-plate skater too timid to venture across the ice without the prop of a chair.

With their stark black shapes on bare paper, Nicholson’s prints remain a radical marvel. He uses colour so sparingly it might amount to no more than a flower seller’s rosy blush or the green dot of a greyhound’s eye. Whistler, his monocle slung raffishly low, casts the most abbreviated of shadows from his soaring black height, a single curl rising up in a devilish horn. Queen Victoria is a monstrous black hump, heavy jowls and owlish eyes brilliantly summarised against a bleak midwinter of empty page. The Skye terrier at her feet doubles as a miniature Highland cow.

Here is Nicholson’s wonderfully concise windmill logo for William Heinemann; his illustrations for Margery Williams’s cherished story The Velveteen Rabbit; his theatre designs, book covers, posters and costumes, even the frock he painted all over for his second wife Edie.

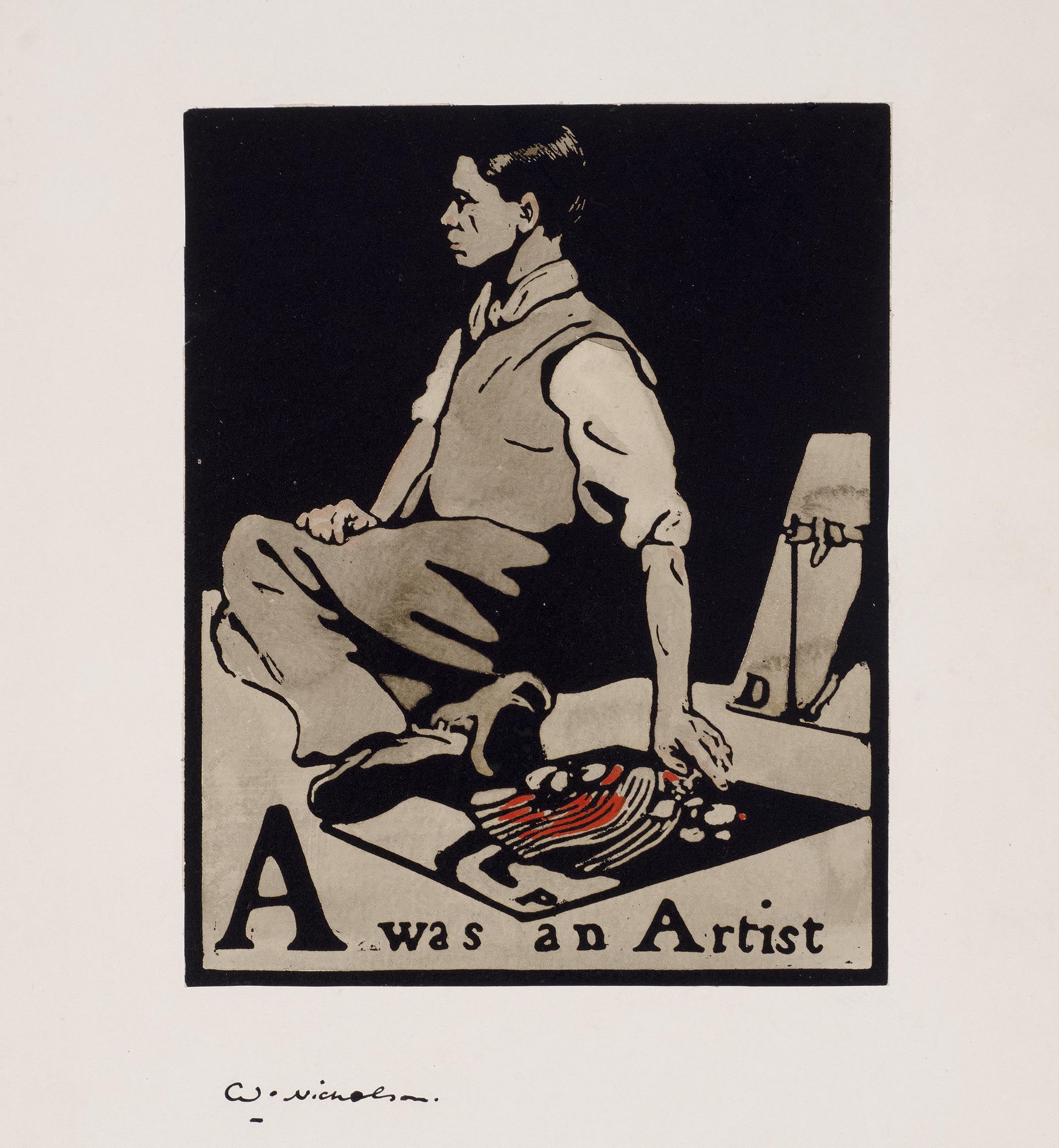

‘A period condensed in proverbial images’: the artist himself appears in just one of his alphabet woodcuts

His best-loved paintings are of silver bowls shining out of surrounding darkness on tabletops, sparse objects – gloves, green peapods – reflected in their surface. These are bestselling postcards for museums from Tate Britain to the National Gallery of Scotland and to see the originals at Pallant House is to understand why. Small, certain, skilful, very clear of definition and contrast, they are perfectly made for reproduction.

Nicholson had a peripatetic life, living in Buckinghamshire, Sussex, Wiltshire and Mayfair with a succession of wives and mistresses. He was among the first generation of English artists to be steeped in national museums – you see the effects all through this show. He goes to India and paints the tall trees in the manner of Hobbema’s Dutch Avenue at Middelharnis. He tries, and fails, to paint a blond moppet as a Velázquez Infanta. His beaches and cliffs are pure David Cox.

Encouraged by Whistler, Nicholson took up portraiture in the 1890s. This show opens with a painting of his first wife, the artist Mabel Pryde, sitting sideways in overt homage to Whistler’s Mother (1871). But Mabel is depicted in yellow, against a yellow wall, in a yellow fug into which she entirely disappears. There is none of the suave clarity of Nicholson’s later portraits.

Essayist Max Beerbohm looks fixedly downwards, in 1905, dark against a tawny space borrowed again from Velázquez (Beerbohm caricatured Nicholson in return, throttled by a modishly high wing collar). JM Barrie, with whom he collaborated on the 1904 staging of Peter Pan, stares off into the distance. Nicholson himself appears, incidentally, only as A for Artist, turning away in the alphabet woodcuts. Personality is veiled.

Where is his heart? Hard to tell, until you get to the hand-painted dress or the trompe l’oeil gloves concealing a secret love letter to Edie. Nicholson’s relationship with his son Ben, future modernist art star, is a disturbing narrative through this show. Edie was the son’s lover before she became the father’s wife. Nicholson’s portrait of Ben aged six or seven shows a sad-eyed child, the paint so dry, the image so mute, the boy seems to vanish into the canvas.

His small oils of silver bowls, flower vases, boots, gloves and landscapes are an undeniable pleasure (no wonder so many remain in private collections). Sometimes he departs from convention into singularity: the quasi-abstract Spanish landscape tinged pink at dusk; the moment of radiance as the sun sets on the brow of a Sussex hill; the compact beauty of a solid brass tankard. Nicholson knows he can do it. “Rather a good Down piece I did night before last,” he writes to Ben about a Sussex hill, “looking into the eye of the sun.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The polished reflections don’t always hit the mark, but the pictures glow when they do. In one painting, a silver tea caddy holds a whole miniaturised still life in its sheeny surface. In another, the ring of light emanates beyond the object into the circumambient air. Something is still happening. The painting continues.

William Nicholson’s The End of War lithograph from 1917

About human beings, Nicholson is more or less interested or distracted. The socialite Sybil Hart-Davis has a face so tiny – a fraction of an already small canvas – that who or what she might be is indiscernible. The garden designer Gertrude Jekyll, her greatly gifted hands a salad of wilting marks, sits patiently waiting for the session to be over. Nicholson prefers to paint her boots, in what would become another insanely popular postcard.

By some way the worst canvas in this show gives us Beatrice and Sidney Webb hard at work on either side of a brick fireplace. The floor is a litter of Fabian Society tracts. But this is not half as ludicrous as the oppressive expanse of bricks between the two, laboriously numbered, dominating half the picture.

Nicholson’s facility can be glib, his paintings too pleased with themselves. They sold well and he painted several hundred: picnics, posies, pretty tabletops. But nothing in this show compares to his decisively original woodcuts. English society of the period condensed in proverbial images – F for Flower Girl, G for Gentleman, O for Ostler. The concision of these prints dazzles far more than any of Nicholson’s painted glints.

Photographs from Private collection/Barney Hindle

William Nicholson is at Pallant House, Chichester, until 10 May