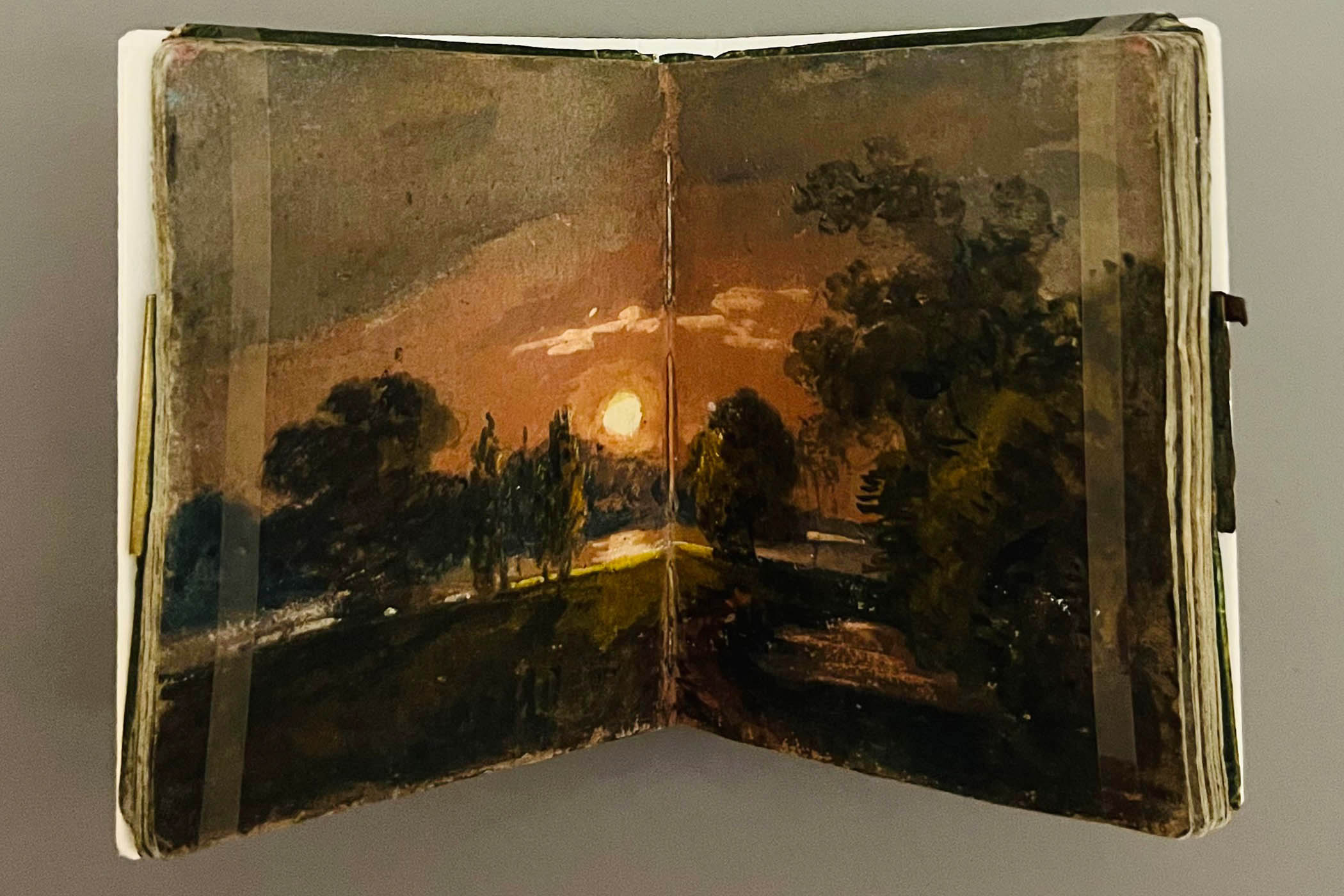

There is an image in this show so startling it acts on the eye like an exploding firework. This comes about halfway through. A tiny watercolour book, no bigger than a wallet, lies open in a glass case. Out of it radiates a harvest moon, burning above darkened fields. The incandescence is so powerful, even on this fractional scale, it seems to set the very pages alight. This is one of the smallest yet greatest works by Turner you will ever see.

In the next gallery hangs a Constable moon, emerging from behind black trees on a lonely heath. This is eerier, colder, slower, painted in oils on a scrap of card. Its alien force makes the hair stand on end. Like so many of the works in this stupendous exhibition, it emerges from a private collection – sight unseen, doubling the thrill. Two entire careers are entwined at Tate Britain in a succession of world-famous masterpieces but also in visions rarely (if ever) seen in public.

The show’s premise is deceptively simple. Turner was born in 1775, Constable in 1776, so this is a joint 250th commemoration. There is also a lively tale of professional rivalry to tell. The Covent Garden barber’s son who never lost his Cockney accent versus the scion of a successful Suffolk miller; hot versus cold; fire versus rain; poetry versus prose, and so forth.

‘One of the smallest yet greatest works by Turner you will ever see’: Sunset over a River, 1796-7, painted in a tiny watercolour book. Main image: John Constable depicts Brighton beach in Rainstorm over the Sea, c1824-1828

Turner is a Royal Academician at 27, Constable has to wait until he is nearly twice that age. Turner’s wanderlust takes him to Alpine glaciers, Tuscan hills and Venetian lagoons; Constable stays stolidly at home. Turner’s rhetoric of sublime effects shows the world dematerialising, matter transforming into energy; Constable’s landscapes are turbulent, claggy, overcast even in high summer, loaded with their heavy jewellery of brushstrokes.

The distinctions are so often invoked that some find it hard to believe these artists could have anything in common. Which is precisely the twist of this show. It wants us to look far more closely at these minds and hands at work, and to discover fundamental similarities when the two are brought together. In its originality and insight, its brilliant selection and compelling texts, this is one of the most exhilarating shows I’ve ever seen.

We are out in the Welsh hills with Turner, rain mottling the page as he paints the jagged crags vanishing into the shower. A passage of empty white paper runs through the watercolour, implying a freezing stream. Now we are on Brighton beach in a rainstorm with Constable, the sea glowering and sparking beneath an oncoming storm. The horizon, scored in with the brush handle, holds the oil sketch in equilibrium just as black paint starts to gush from above. Both images are fiercely experimental.

Constable paints clouds over Hampstead in early September. Meteorologists may be able to calculate the season from his skies, but it is not his exactitude of observation that strikes. His clouds materialise on canvas without coalescing into anything as substantial as shapes, amorphous and ever-changing as any nimbus. And though we know exactly where Turner stood to paint Norham Castle (a sign marks the spot) his landscape is turning into an airy mirage, the Tweed below as vaporous as the sunrise above.

Seascape, landscape, cloudscape: all may be inherently abstract. But the radicalism of these painters far exceeds visual fact. Take Constable’s Dedham Vale (1828), an immense phenomenology of near and far, tiny figures lolling in deep foreground foliage, light striking the Stour as it disappears into the distance. The scene could be Dutch (both painters studied Rembrandt) but Constable divides the picture vertically too, between the tangled embroidery of trees on one side – mazy marks into which you peer as into a bird’s nest – and the motionless white atmosphere on the other, awesome as the ether.

Rain mottles the page in Turner’s Cader Idris – A Stream among Rocks near the Summit, 1798, a watercolour transporting us to the Welsh hills

It is astonishing to think that neither artist was taught to paint in oils. Turner has to make it all up (and is derided by contemporary critics for excessive use of home-mixed yellows). Tate Britain has oil sketches where blade and fingertip are apparent in the surface, shifting the pigment around. And Emma Stibbon, one of four contemporary artists interviewed on screen at the end, makes the revelatory suggestion that Turner must have had a sharpened fingernail to score away both watercolour and oil.

Both artists wash veils of light across the smallest strips of paper to praise the sun, its rays seeming to pass through time as well as space in Turner’s art. With Constable, you sense its lingering heat in deep cornfields and shallow riverbeds. Evanescence and solidity appear to alternate, like the individual gallery rooms, between the artists. But then the curator, Amy Concannon, audaciously shuffles the works together in one gallery so that you can no longer tell quite who has clambered up Snowdon and who is out on Coniston Water.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Pinholes in each corner of a bright August oil sketch tell us that Constable tacked the paper inside the lid of his paintbox, which then appears in the next gallery, complete with Cumberland pencils. His collapsible sketching chair might have been made for a child. Turner’s fishing rod is also poignantly modest, like the wallet he recycled for carrying watercolour pans in his pocket. Everything you see appears quick with the maker’s mark.

John Constable, Hampstead heath with a Rainbow, 1836

Another curator might have sidestepped the old rivalries: Turner adding a red dab to a picture to upstage Constable at the RA; Constable dubbing Turner he “who would be Lord over all”. But Concannon actually restages their 1831 standoff, showing just how pernicious the annual exhibition could be even back then. Constable, on the RA committee, hung his enormous Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows – complete with a polished banister of English rainbow above a calculating reprise of The Hay Wain – right next to Turner’s Caligula’s Palace and Bridge, infested with ludicrous Roman figures. Six feet of excess, in each case, made to attract money and crowds.

But aside from this mad spectacle, Tate Britain’s show is a thrilling interplay of masterpieces – from Flatford Mill (1816-17) to The Blue Rigi (1842) – with smaller paintings, quickfire sketches and wild new images. It peaks and then it peaks again: Turner sunsets in one room, Constable clouds in the next, leading to the late works that exceed anything in English landscape art.

Constable’s Sketch for Hadleigh Castle (1828-9), with its ruined towers and harbinger crows circling the icy white air above desolate flatlands is a vision of fear and grief so roiled it troubles the mind. Turner’s Staffa, Fingal’s Cave (1832), shows the sun sinking as a ship leaves the lonely basalt rocks behind to journey across turbulent black waves.

These paintings are not made to appeal only to the eyes. Beyond illusion, beyond simple description, they intensify the senses so that the world outside the gallery is changed through the act of laying pigment upon a surface. The effect of this show is not to make you choose between Turner and Constable, like some facile competition, but to raise each artist – through joint ambition – even higher.

Turner and Constable: Rivals and Originals is at Tate Britain until 12 April 2026

Photographs by Royal Academy of Art/Tate