Does the Turner prize matter any more? Critics love to deride the annual award for contemporary visual art, but judging by the reaction to the announcement on 9 December that Nnena Kalu was this year’s winner, their interest hardly seems to be waning. The fevered pitch of the press coverage suggests the prize may in fact matter too much – at least enough to distract from the work it intends to celebrate.

Kalu’s abstract, charcoal drawings and hanging sculptures, the latter fashioned from colourful paper, gaffer and VHS tape, are the least overtly political of the works by the four nominated artists yet by far the most politicised. That’s because the 59-year-old Glaswegian is learning disabled. Autistic with limited verbal communication, she has not provided curators or critics with an interpretive framework for her practice. Her art must speak for itself.

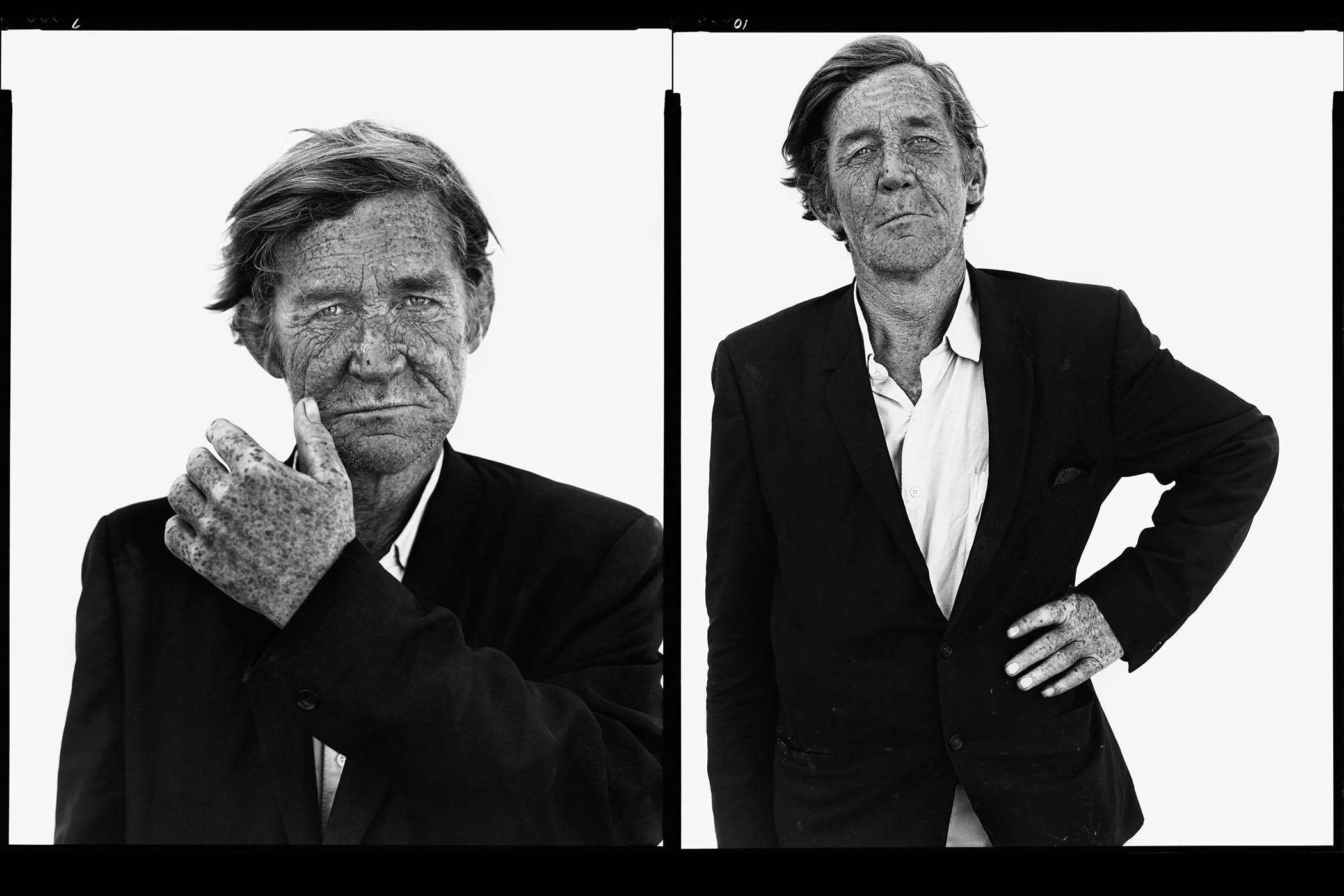

Works by Nnena Kalu go on display during the Turner prize 2025 exhibition. Main image: the artist in front of one of her expressive charcoal canvases

That has made some people uncomfortable. The Times’s art critic, Waldemar Januszczak, decried the judges’ decision as “virtue-signalling”, writing that “it is not the job of art to confuse therapy with talent. Nor is it the task of the Turner prize to play doctors and nurses or involve itself so flagrantly in the collection of medical Brownie points.” In the Telegraph, Alastair Sooke was more measured, accusing the panel of a “collective act of goodwill” rather than “tough-minded aesthetic judgment”.

Kalu’s supporters also appeared to put the artist before the art. “This is a major, major moment for a lot of people. It’s seismic. It’s broken a very stubborn glass ceiling,” Kalu’s studio manager, Charlotte Hollinshead, said during the award ceremony.

So what of the art, then? I’ll admit I dismissed it too, before I made the trip to Bradford to see it in person. In photographs, I thought Kalu’s sculptures looked like desultory piñatas. But entering the gallery at Cartwright Hall was like stepping into quicksand; the work sucked me in. Kalu’s drawings, with their fast, confident strokes, have an undeniable gravitational pull. They reminded me of furiously overworked charcoals by Judith Bernstein and Lee Lozano, artists whose insistently repetitive marks have often been interpreted as expressions of feminist rage. The words of Cy Twombly also came to mind: the late painter described the scribbles on his own canvases as “childlike, but not childish” – a language to be keenly “felt”, rather than deciphered.

Abstract expressionists such as Twombly, Jackson Pollock and Clyfford Still were praised for the spontaneous originality of their compositions, which critics such as Clement Greenberg described as springing from an “unmediated unconscious”. The splashy gestures they left on canvases were presumed to be a kind of unfiltered id – but art historians have since learned from scouring their archives that those strokes were carefully measured. The narrative of spontaneity simply helped support a myth of white male genius, one that eventually hardened into a stereotype: the AbEx painter was a reclusive master, possibly a drunk, whose antisocial behaviour we might diagnose today as a form of autism. Left out of this picture, of course, were women, people of colour and the learning disabled.

It’s nonsense, of course, but we remain obsessed with such stories. They influence the kinds of neurodivergence we celebrate in art and the kinds we continue to marginalise. They permit us to swerve lazily towards biography to explain away work we struggle to understand.

I don’t mean to suggest that Kalu’s art ought to be beyond criticism – only that it must be judged on its merit alone. Anything else does a disservice not just to her, but to all the artists who have been dragged into the quagmire of identity politics, whether they like it or not.

Related articles:

Photographs by James Speakman/PA, Andrew Benge/Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy