Photo illustrations by Mike McQuade

Throughout my childhood and beyond, I can’t help but notice that men like my father and my male classmates are often mystifyingly angry, erratic, even dangerous. The Pacific Northwest, where we live, was known for five things: lumber, aircraft, tech, coffee and crime. Weyerhaeuser, Boeing, Microsoft, Starbucks and serial killers. Every decade, the headlines: Why Are There So Many Serial Killers in the Northwest? There is no answer. There are three men who live in what you might call the neighbourhood, within a circle whose centre is Tacoma. Their names are Charles Manson, Ted Bundy and Gary Ridgway. What are the odds?

Growing up on Mercer Island, a prosperous suburb of Seattle located in Lake Washington – an enclave renowned for respectability and safety – I live up the street from a boy who would become a serial killer and murder three women in 1990. I live a few blocks from a man who became a notorious arsonist in Seattle. I attend high school with a boy who would eventually murder his mail-order bride and another who stalks his girlfriend and blows up her college dorm building, killing himself.

No one knows what causes these incendiary episodes, but we’re all living beside the massive federal interstate that crosses the island, awash in leaded exhaust, and in the plume of a smelter that spewed lead over 1,000 square miles of Puget Sound.

When I’m eight, a man down the block, a Vietnam veteran, finds himself in the grip of wrath.

On the morning of Wednesday 16 July 1969, Apollo 11 lifts off, and the house up the street blows up. My sister and I run to the picture windows that look out over the lake, staring at the sky. We are home alone.

My sister thinks a plane from Boeing Field has made a sonic boom. This is the summer of sonic booms, the summer of Sugar, Sugar on the radio and on a record you can cut out from the back of a cereal box. Boeing is planning the world’s first “supersonic transport” after President Kennedy announced his plan to compete with the Concorde. The Seattle SuperSonics, the basketball team, is named for it. Whenever we hear a plane break the sound barrier, it makes a thud in our heads that spreads, the way footsteps on a dock sound when you are swimming underwater.

Then we see smoke. It is coming from the house up the block, a house on a rise on West Mercer Way, overlooking the street. On an island of wooden houses, this one is clad in brick. In a neighbourhood of modest, ranch-style structures, it seems high, not low.

It looms. One of my third-grade classmates lives in that house, an eight-year-old girl named Jenny, who has two stiff, straw-blonde braids that spring out of the back of her head like Pippi Longstocking’s.

The explosion is so powerful and the flames so intense that the fire chief thinks dynamite is involved. The local newspaper echoes my sister, reporting that “neighbours described the first blast ‘like a sonic boom’.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

It’s not a sonic boom. It’s not dynamite. It’s something in the basement: a hissing propane gas container from a camp stove deliberately cocked on and placed next to the home’s furnace by Jenny’s father, Dr Stephen L Tope Jr, a 34-year-old anaesthetist and former lieutenant commander and medical officer in the Navy who has recently lost his job at Virginia Mason Hospital, in Seattle. He has served multiple tours as a flight surgeon in Vietnam. He lets the basement fill with propane fumes, then turns the furnace on. In July.

At the time, I think, this is what dads do. They get mad and blow up the house

At the time, I think, this is what dads do. They get mad and blow up the house

The house explodes as he and his wife and two of his four fair daughters, aged five to eight, are upstairs, preparing to go on a trip to Blaine, on the Canadian border. The two other girls are outside, playing in the yard. The floor upstairs billows, like a rug being shaken. Screaming, Dr Tope’s wife pushes her children out the door. He walks into the bedroom and fires a bullet into his right temple.

The house burns fiercely. Scorched black bricks blown 20ft from the house are scattered beside the foundation when I walk past it on my way to school that autumn. The doctor’s body is found in that back bedroom. His wife and daughters are uninjured, but their dog, a Weimaraner, will not leave his master’s side and dies in the fire.

Dr Tope misses the moon landing by four days. Chappaquiddick by two. In California, the Zodiac Killer is just getting warmed up.

At the time, I think, this is what dads do. They get mad and blow up the house.

In years to come I will wonder about my own dad, watching his face get red when he’s angry, watching one day as he beats a broken lawnmower with a sledge hammer. If he gets mad enough, will he blow up our house? What exactly are men capable of, I’d like to know, and why?

In the 1970s, life is cheap and, as the decades roll on, it just gets cheaper.

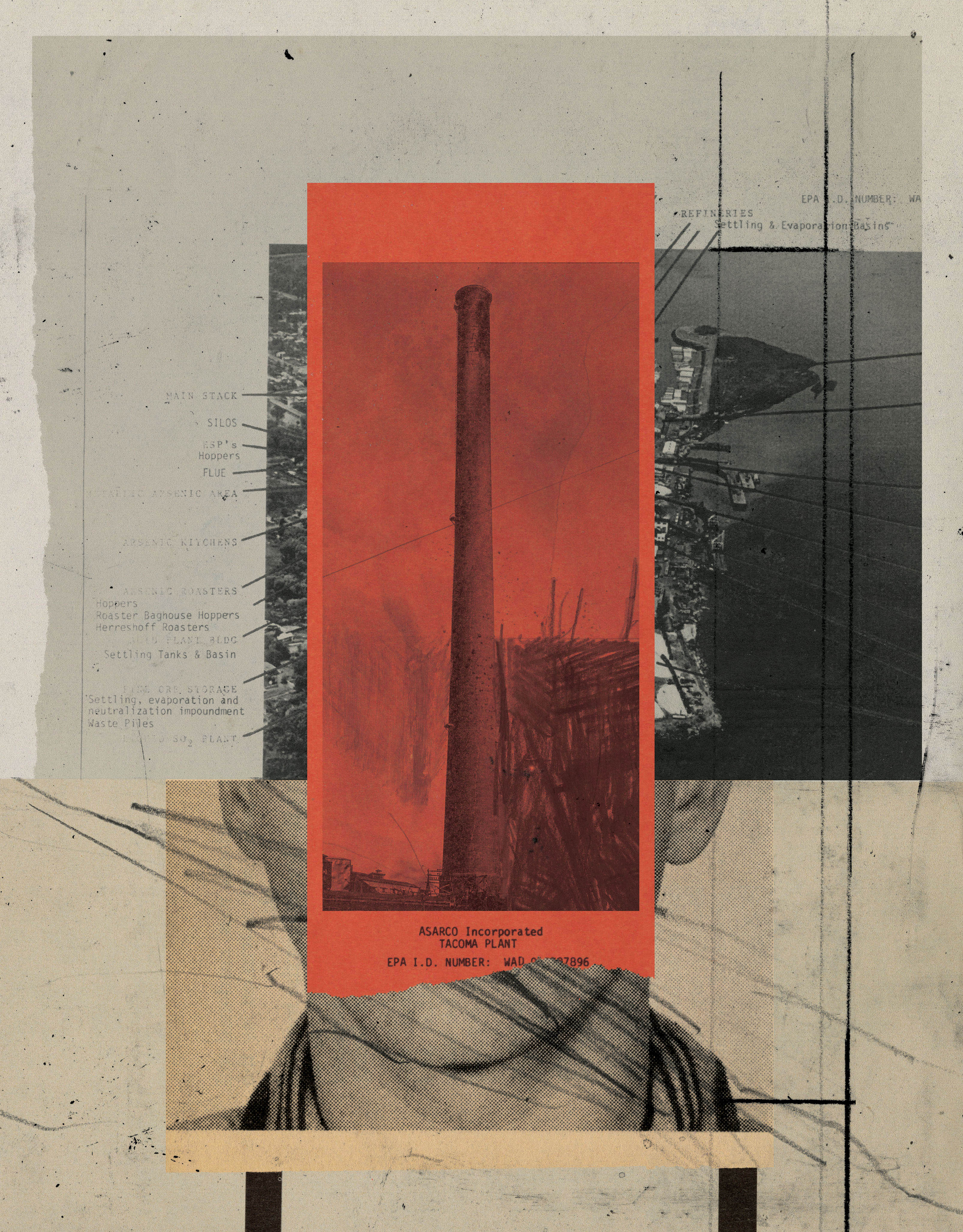

Mercer Island lies within the plume of the Guggenheims’ smokestack, proud landmark of the American Smelting and Refining Company. At the waterfront smelter in Tacoma, 20 miles from the Island, they’re burning ores to make copper and other precious metals. They make arsenic, for pesticides. Near the stack, teenage Ted Bundy is delivering newspapers in Tacoma and scouting out pornography in trash bins. At 14, in 1961, he either does or does not kill an eight-year-old girl, Ann Marie Burr, whose body has never been found. Living near Sea-Tac airport, also in the plume, teenage Gary Ridgway stabs a six-year-old boy in the abdomen for no reason. I don’t know it yet but there’s another budding killer growing up down the street from me, a kid named George.

To some extent, I can see what’s happening around me. In 1974, I can see the news about women disappearing from their beds, from college campuses, from highways in Washington State. I can see that Patty Hearst is being held hostage, but on 15 April 1974 she is spotted on surveillance camera in a branch of Hibernia Bank swinging an M1 carbine while yelling, “Up, up, up against the wall, motherfuckers!” I can feel an atmosphere of delinquency and rebellion in the air.

What I can’t see is more insidious. I can’t see the crime rate rising in Tacoma by 20% in 1974. I can’t see the price of lead climbing sharply during an unexpected commodities boom that year. I can’t see lead and arsenic in the air, showering down upon us, the particulates sifting into Lake Washington where we go swimming in the summer. Nobody can see these microscopic gifts from the smokestack, and because we can’t see them, it’s as if they don’t exist.

And yet scientists know. Doctors know. They know that what makes the Guggenheims rich means that children are increasingly exposed to lead in the environment, lead that affects their developing brains, making them more impulsive, more angry and more aggressive. More prone to violent behaviour as adults. The Guggenheims don’t care. Their smelters aren’t just in Tacoma, they’re all over the West, in Idaho, Montana, Utah, Texas, Arizona and California. They’re all over the world, adding lead to air that’s already full of it from leaded gasoline, lead paint and lead dust.

I’m reading Ranger Rick, a nature magazine for kids, learning about Rachel Carson, who said that pesticides are killing the birds and the bees and will eventually kill us all.

In the new year of 1978 on Mercer Island, adults are preoccupied with juvenile crime, vandalism and property destruction involving multiple cases of felony arson. Throughout the 1970s, a number of serious and potentially life-threatening fires are set, presumably by island children. A portable building at an elementary school is burned, totalling $22,500; a fire at South Mercer Junior High costs $70,000; another at Mercer Crest, $20,000.

Professor Ellis Evans, an expert on adolescent development at the University of Washington, is brought in to tell parents that “national trends show steady increases in the number of youthful offenders each year this decade”. He talks about drugs and alcohol and how they alter the nervous system, but he doesn’t talk about other substances in the air and the water. He doesn’t talk about lead in the lake and arsenic accumulating in the needles of pine trees.

Much of the vandalism remains trivial, if expensive and annoying – kids kicking in lockers, breaking windows and lights and applying graffiti to walls. An elaborate mural of marijuana leaves and bong pipes appears at Lakeridge Elementary. The district supervisor of grounds and maintenance notes dryly that “the spelling has improved over the years,” but decries the constant thieving of costly lighted EXIT lights, stolen to decorate rebellious teen rooms.

I don’t steal signs, but am fixated on preparing my own exit. I, too, am a prowler. If I wait until my parents are asleep, I find that I can creep into the living room by keeping to the side of the hall, where the carpeted floor doesn’t squeak. There, I can write in my notebook, look out into the night and even watch television with the sound tuned as low as it will go, my ear pressed against the speaker. In this way, I am able to see many valuable episodes of Star Trek, including The Menagerie in which Captain Pike and the woman “Vina” are kept in cages by a superior race of beings. The humans don’t know it, but they’re disfigured and dying. They can’t see it, because their minds have been taken over by a powerful reality distortion field. They escape, but in the end choose to return to their captors, wrapped in the illusion that they are whole and well.

Dystopia appeals to me, and I’m quietly contemplating the end of human civilisation.

When I’m 18, I go to university and live in a sorority much like the Chi Omega house at Florida State in Tallahassee. That’s where, in 1978, Ted Bundy, having escaped from jail in Colorado, kills two women, Margaret Bowman and Lisa Levy, and brutally assaults others. Sororities are built on copycat plans, and I live in the Lisa Levy room. I’m 19 when he finally stands trial for a few of his crimes, and when I run upstairs at the sorority I can see the hallway schematic from his trial in my mind. He’s been a part of my world since I was 13.

I have escaped, but not everyone can. In the early hours of the morning on 12 May 1980 Jason Perrine, 16, a freshman at Mercer Island High School, revs the engine on his girlfriend’s sister’s 1972 Chevy Camaro and blasts Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Free Bird on the car stereo. Sitting in the passenger seat is his 15-year-old girlfriend, Dawn Swisher.

Jason is estranged from his parents and living at Dawn’s house. He’s planning to drop out of school and start a new job at Jack in the Box, but then he decides that’s a stupid plan. So he revs the engine and drives the Camaro at 110mph into the gymnasium wall at North Mercer Junior High, the school where I studied grammar and wrote about Richard Bach’s allegory Jonathan Livingston Seagull. Jason is killed instantly. Dawn ducks under the dashboard and survives, albeit with serious injuries. The gym is destroyed.

Jason, it transpires, has been troubled by Richard Bach’s latest regurgitation of Mary Baker Eddy’s thoughts, entitled Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah. The book is about a guru who teaches the author that nothing is real. Everything is an illusion, and no one ever dies. It’s exactly what my father, a devout Christian Scientist, believes, but Jason has decided to put it to the test. When I hear this story, whispered by my mother from her refuge in the laundry room, I feel a sneaking admiration.

What are the odds that Mercer Island would spawn both a serial killer and a mass murderer? Pretty good, apparently

What are the odds that Mercer Island would spawn both a serial killer and a mass murderer? Pretty good, apparently

Jason’s explosive act inspires international press coverage and endless editorial hand-wringing over teen angst, peer pressure, overindulgent parents and a culture of permissiveness. After some time has passed, Jason’s anguished father puts it down to his son being “a casualty of… the breakdown of the family, the drug culture… and the violence and brutality in society.” Asked for his response, Richard Bach declares himself indifferent because, he says, nothing is real. What are the odds that Mercer Island, a most liveable suburb according to Ladies’ Home Journal, would spawn both a serial killer and a mass murderer? Pretty good, apparently. George Waterfield Russell Jr, killer, and Martin Pang, arsonist, grow up within blocks of each other and of me and of the I-90 tunnel.

Mercer Island is as beautiful as it ever was, the water on the lake is sparkling, the views as serene. But for some of us who knew it in a different time, it’s slightly haunted by ghosts of the past, a drowned forest offshore, a sunken bridge, a shattered school gymnasium, long swept away. East Seattle School, built in 1914, the oldest public building on the island, was demolished for no good reason in 2021. Last time I saw it, all that was left was a muddy pit. There are places where money means more than history.

My father, who loves Mary Baker Eddy, never learns the difference between fantasy and reality, and sometimes I wonder whether anyone else has either. You don’t have to be a religious zealot to deny what men and corporations are capable of. All you need is the mind of a serial killer, someone who looks at another person and sees only his own gratification, someone who looks at lead and arsenic and sees not poison but profit.

The Tacoma smelter was wiped away: it closed in 1986 and the smokestack was blown up years later. After a thorough scrubbing, condominiums were built on the site, units with glorious views across the bay. But standing on the waterfront, all I can see in the waves lapping the sanitised shoreline are the eyes of Ted Bundy, flickering and dissolving and never fully disappearing.

Murderland by Caroline Fraser (Little, Brown Book Group, £25). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply.

Photos used in illustrations by US National Archives; Alamy; Emily Matthiessen