In spring 2014, a group of young political activists occupied the floor of Taiwan’s legislature. Their Sunflower Movement led to the shelving of a controversial trade deal with China, but 21 of them were later put on trial for their actions. “I thought it was quite exciting,” recalled Lin Fei-fan, one of the most prominent of the protesters, adding: “I was ready to take responsibility for my actions.”

In Beijing in 1989, or Hong Kong in 2019, those activists would almost certainly have been jailed for years. In Taiwan, they were acquitted. The freeing of the Sunflower protesters was a key moment in east Asia, showing that a government could recognise direct political protest as a valid pathway to social change, rather than an impertinent challenge to untrammelled state power. Today, Lin Fei-fan is the deputy secretary-general of Taiwan’s National Security Council, and one of the many voices interviewed by Chris Horton in his compelling and important book on the island’s recent history and politics.

In the past few decades, Taiwan has changed from a political backwater to a producer of semiconductor chips essential to the global economy, as well as a flashpoint that could start a global war between the US and China as Beijing makes increasingly confrontational demands to control the island. Horton, who has years of experience reporting from China and Taiwan, argues that the wider world needs to know more about the dynamics that have led to the current unstable situation.

Ghost Nation is a crisp and deeply researched account of key events: Japan’s colonisation of Taiwan, the cold war era when the island was (increasingly oddly) recognised as the true government of China by the UN and US, and more recent years, when Taiwan lost its recognition at the UN but became a prosperous, hi-tech democracy with a vibrant media and civil society. Horton also gives a chilling account of what may happen if China invaded Taiwan. Although its topography would make it a tough campaign even for China’s well-equipped People’s Liberation Army (PLA), there’s no doubt that it would lead to huge human and financial costs for Taiwan, the US, China and the global economy.

Horton’s analysis of Taiwan’s contemporary politics draws mostly on the worldview of the ruling Democratic Progressive party (DPP), arguing that there has only been one short and very unhappy period of unification between Taiwan and the mainland, under Chiang Kai-shek in 1945-49, and that the two societies have grown apart as China has become increasingly authoritarian and belligerent about bringing Taiwan under Chinese control. He gives an excellent account of the subtle positioning of figures such as former president Tsai Ing-wen, who had to navigate between increasing demands at home for independence and angry threats from Beijing at even the suggestion of such a move.

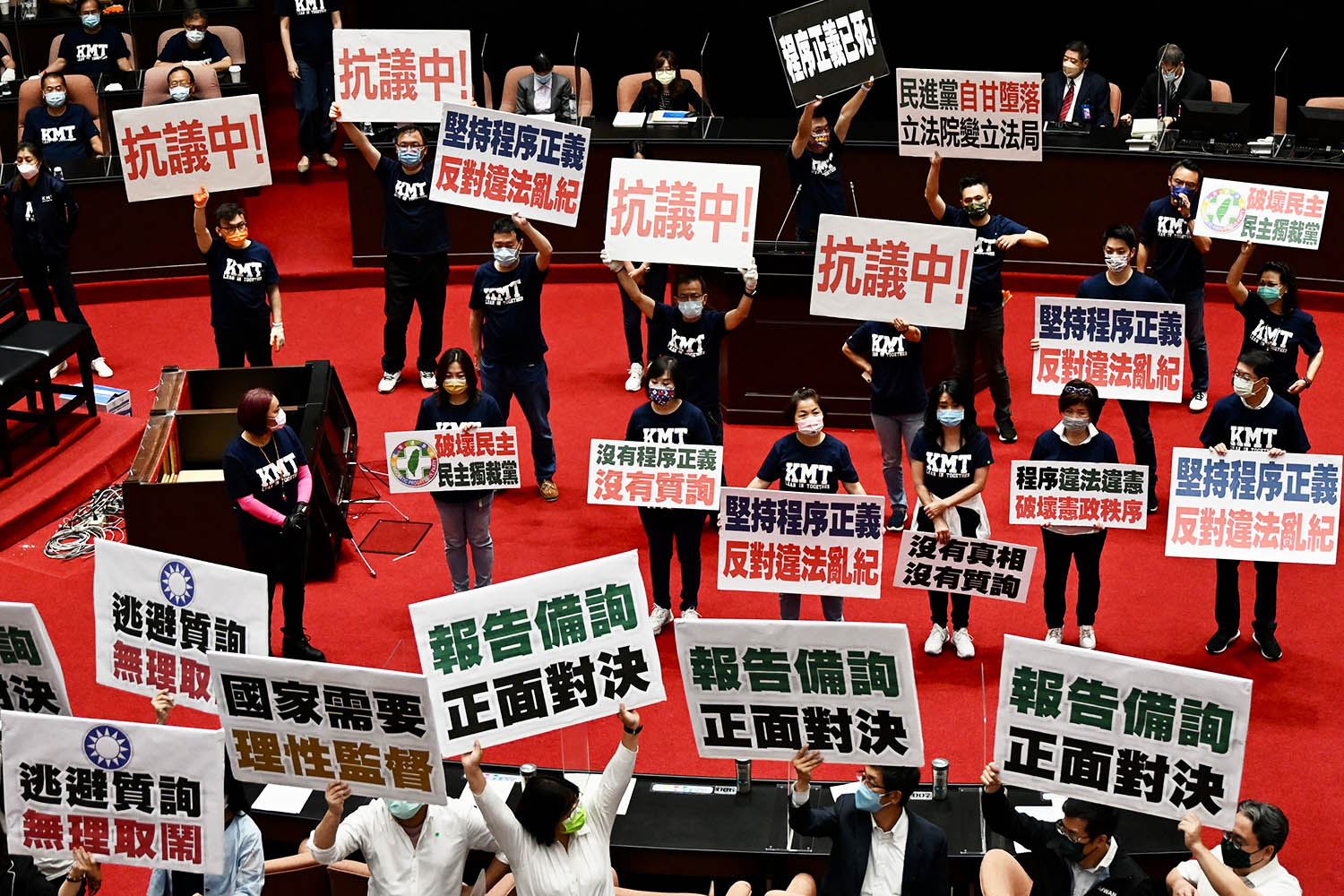

The book is less strong on Taiwan’s opposition parties. The KMT (Chinese Nationalist party) holds the balance of power in the legislature, yet it is generally treated with broad-brush descriptions such as “pro-China” or “ethnonationalist.” This makes it hard to explain why, as Horton acknowledges, the opposition regularly wins crucial elections such as for Taipei’s mayoralty. The book doesn’t seem to have any interviews with contemporary KMT politicians or their voters. And there’s barely any mention of the third party that caused such a stir in the 2024 election, the Taiwan People’s party (TPP) under maverick leader Ko Wen-je. A recent report by theGlobal Taiwan Institute (non-partisan but, as its name suggests, not exactly pro-Beijing) showed that a staggering rise in youth support had boosted the TPP as frustrations over a poor economy and expensive housing costs drove disillusionment with both major parties.

In many cases, Horton is quite right: there are indeed legislators, business people and civil society operatives in Taiwan who are working illicitly or openly for Beijing’s goals. But there are plenty of opposition supporters who are genuinely worried that a move toward independence might trigger a confrontation with the mighty authoritarian neighbour that can’t be wished away. They think the present fragile status quo is worth preserving while Taiwan builds up its own defences and hugs the US as close as possible. Meanwhile, Taiwan’s champions are also hedging their bets. Companies such as TSMC, the world’s most important chip manufacturer, are investing in the US to keep Donald Trump happy; they are also investing in China just in case those chips fall the wrong way.

This complexity matters, because Taiwan’s democratic politics is becoming increasingly polarised, and that spells danger for its civil society. Its shift from an authoritarian state abusive of human rights to one of the most liberal societies in the world did not happen by accident, but, as Horton shows, because of the self-sacrificing acts of democracy activists. Taiwan today offers a powerful challenge to China, asking why a liberal and free society should choose to join a state that would restrict or end those rights. So far, Beijing has failed to find a convincing answer.

Rana Mitter is ST Lee Chair in US-Asia Relations at the Harvard Kennedy School. Order Ghost Nation from observershop.co.uk to receive a special 10% discount. Delivery charges may apply

Photograph by Sam Yeh/AFP via Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy