Is it more noble, or more true, to face the gods of this world in the intensity of solitude than in the warmth of community? That is what is asked by Making the Cut, Max Olesker’s account of his conversion to Orthodox Judaism. Olesker, 38, is a comedian by trade, and there is much to laugh about in his account of the idiosyncrasies of Jewish life. But a great deal of anguish also shapes his experience of an almost unimaginably challenging – and isolating – process.

I say almost, because I have done something of the sort myself. Last April, I plunged into the waters of the Jewish ritual bath, the mikveh, for a spiritual cleansing that completed my own conversion to Liberal Judaism. Like Olesker, I was initially motivated by love but found faith along the way. Like Olesker, I felt emotions that ran the gamut of ecstasy, resolve, anger and pain.

Olesker meets his partner, Eliana, while he is performing at the Edinburgh fringe. A year later, they tearfully break up because she is from the Orthodox tradition and he is not. He agrees to convert and they get back together. Then the even harder bit begins, and the ocean of difference between Orthodoxy and Liberal Judaism, its less rigid cousin, becomes apparent.

My conversion required me to attend the synagogue for adult learning classes and major holidays. Olesker has to go every morning. I was gently encouraged to develop a tradition that marks Shabbat, the Jewish day of rest, while Olesker has no other option. He must unplug from all modern life for 25 hours each week. For the entire course of the process he is not allowed to touch Eliana, whose faith demands his conversion if they are to remain a couple. When he is more than a year into his journey, he moves to Hendon in north London, where he spends several months living with an approved family to immerse himself in the observant lifestyle. These are things he embarks upon “entirely in a vacuum”, at the whims of an “unanswerable authority”.

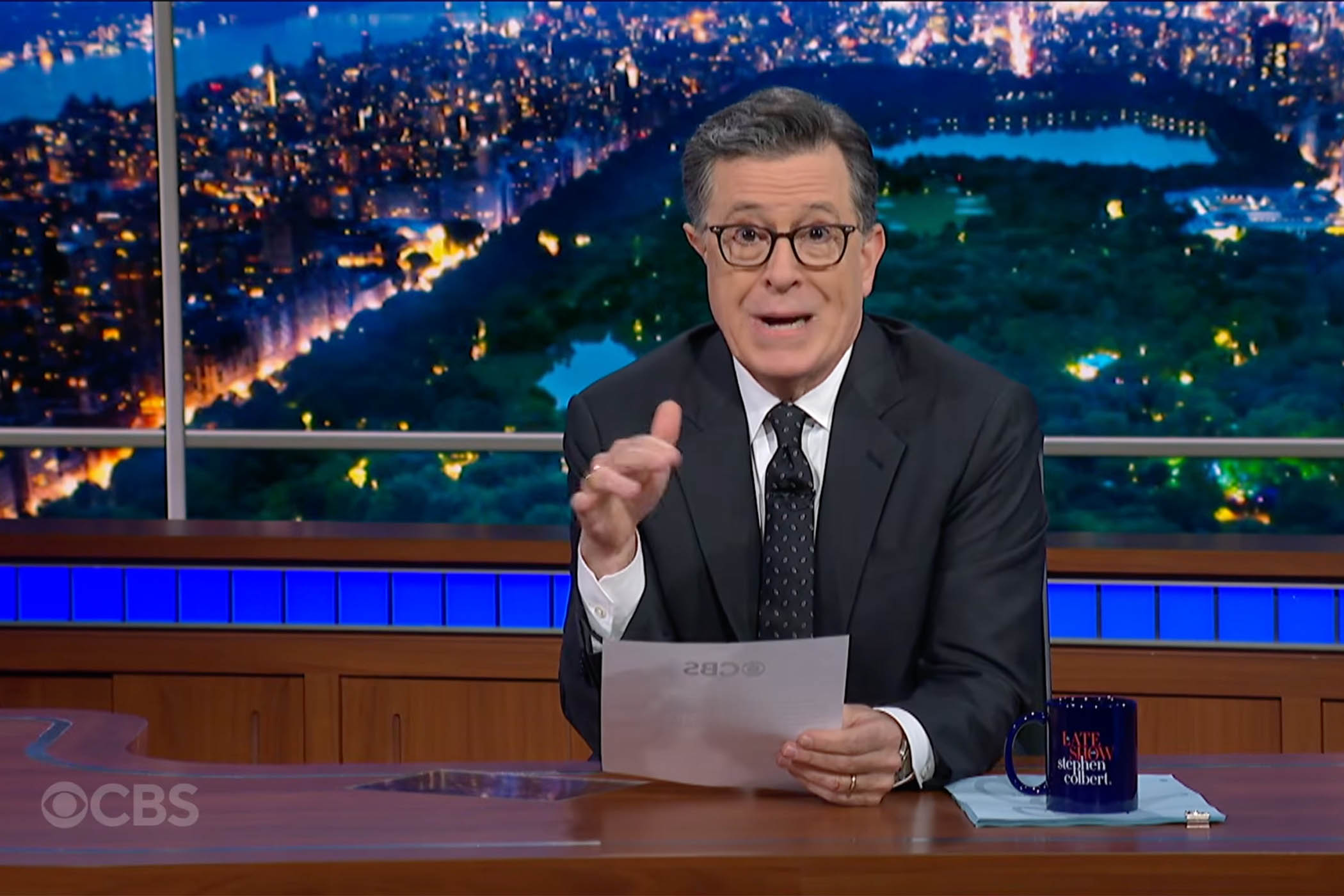

Above: Xavier Greenwood celebrating his conversion with his partner’s father. Main image: Max Olesker and Eliana on their wedding day.

The unanswerable authority is not God but the London Beth Din, the central religious authority for Orthodox Jewish communities in the UK. Its members are the arbiters of Olesker’s fate and appear determined to throw obstacles in his way. It takes six months for him to receive an application form to be considered for conversion, and several years to see it through to completion. The Beth Din takes issue with his career – though he would not be the first comedian to be Jewish – and even suggests monitoring him after his conversion because it disapproves of the website he set up for guests to his wedding. Olesker asks the reader to imagine a process designed to “bring someone as close as can be envisaged to God himself”. His conversion is “the opposite of that”.

It also seems quite lonely. I never could have converted without my partner by my side, without the quiet encouragement of my rabbi, without the friends who counted me into their beats of Friday night dinners, without the other would-be converts to whom I was introduced by my synagogue. Every one of these things energised me and brought me into a community before I had officially joined it. The process Olesker describes sounds spiritually exhausting.

Like Olesker, I was initially motivated by love but found faith along the way

Like Olesker, I was initially motivated by love but found faith along the way

Perhaps that’s the point; a way to strip someone down and make them anew. But to convert to Judaism is to join a people who stretch across distance and time, who have performed the same weekly rituals for thousands of years and against all manner of hardships. Olesker gets access to this in Hendon, with its rich concentration of Jewish life, but at the expense of other important communities which he is asked to move away from. And it doesn’t seem like the authorities who govern Olesker’s conversion care much about making him feel like he is on a journey with fellow travellers. “There’s not a single suggestion that it might be beneficial to spend time with people experiencing the same disorienting series of events as you,” Olesker writes. “Nothing so vulgar as ‘pastoral support’.” He was born Jewish, but that is not enough for the Beth Din because his mother converted into a less observant tradition.

I admire Olesker’s willingness to admit his mixed emotions around the process. I worry I would sanitise an account of my conversion, for fear that my Judaism would somehow be revoked for telling the unvarnished truth. Thankfully, the story ends well for Olesker, as it did for me. He converts, and concludes it was worth the effort. He lets the rage burn away and gazes upon his wife at their wedding, “spinning in the centre of it all”. Love can make us do so much.

Olesker’s account felt both familiar and strange. What does it mean that I’m not sure if I could have done what he did? Does this make me any less of a Jew? Does it make me any less of a partner? I am assured by the words of a rabbi with whom Olesker consults: “The decision cannot be based on logic. It’s something higher than logic.”

If conversion is higher than logic, it is above counterfactuals too. To be born Jewish and wear this with pride takes courage, when history shows it is easier to hide. But to become Jewish is to choose, whatever the tradition. Few things are more noble, or more true, than that.

Making the Cut: An Unorthodox Love Story by Max Olesker is published by Ebury Press (£18.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £17.09. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Divine Day Photography, Tom Pilston for The Observer

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy