Graeme Richardson’s first collection is a frank and funny confession about life as a parish priest. Alongside lofty odes to the “sanctuary of my soul”, “hell and eternal torment” or “flesh in exaltation” are down-to-earth reflections on fatherhood and fate.

Having grown up in Nottinghamshire and served as a member of the Church of England clergy in Hertfordshire, Birmingham and Oxford, Richardson now works as an archaeologist in Germany. He draws on both strands of his career for poems grounded in the graveyard “glaze of soil-ripple worms” and mud that harbours “gut-feelings of fear and revulsion”. He also interrogates the comic irritations of everyday life, musing on missed trains and the mock-tudor pretensions of the posh end of town.

There are plenty of enjoyable moments in Dirt Rich – sarcastic graveyard owls, and jam sandwiches snaffled from pockets by pit ponies – though my favourite poem is Dust-Bunnies in the Playboy Mansion, a tongue-in-cheek tale of sins committed while hoovering the cathedral. “God, the perils of the flesh were tiring”, he admits, struggling “to / control the enormous throbbing nozzle” while sucking up God’s “cute furry / creatures [...] with glee”. Skin flakes read like scripture, providing “enough DNA […] to conjure Frankenstein’s congregant and lead him to the font”.

Richardson uses humour as he would a hymn: he knows when to sing and when to slow, and when to change pitch entirely. “Under the railway bridge, I think of jumping. / Becoming [...] a dot,” he writes in Viaduct. If the “peaks and troughs of our life” total nothing but a “puddle – / why not flatten them here?” Why not be “Run over by / gravity” rather than “die in a mess, / on a care-home’s plastic cushions”?

Richardson’s rhymes take on a ritual quality. Many of these poems have the quality of a prayer

Richardson’s rhymes take on a ritual quality. Many of these poems have the quality of a prayer

Richardson is also poetry critic at the Sunday Times. In the pages of newspapers and magazines, poetry reviewers tend to be seaweed nibblers, swimming in the shadow of those literary leviathans, the fiction and nonfiction reviewers (incidentally, Richardson has a delightful undersea image of hedges catching “as kelp catches; / in them, scraps of jellyfish plastic”). Rarely do we unsettle the waters – we’re lucky to make a ripple. Yet one review by Richardson recently caused a maelstrom.

Having read his description of Len Pennie, who rose to fame through TikTok, as “Scotland’s worst poet since William McGonagall” – and his claims that her poetry, dealing with depression and sexual abuse, is unoriginal and “execrable” – I was not expecting such heartfelt awareness of the fragility of human spirit in Richardson’s own work. The “soul” is not always as strong as “a seam of coal, / packed with power but hard to break”, he writes, summoning his childhood in a mining town. Although intrigued by the pomp of Porsches and picket fences, Richardson honours the skips, scrapyards and superstores of Mansfield, where traffic “snarls” at “boarded-up” windows and “the furious scribble of briar, crossing-out a derelict lot”.

At times his spirit wavers: “Drank a quart of whisky neat. / Hoped to drop. Stayed on my feet,” he writes in To the Quick. Sadness flows poignantly in After the Death of a Child: “The dead live on in memory? Not true. / They lodge there dead, and yours not theirs the hell. / The world without them waits, besieging you; / Their corpse within you, poisoning the well.” As “the body collapses” like “the lancing of an abscess” and hearts weep like open sores, Richardson’s rhymes take on a ritual quality, tolling hope like Sunday bells. Many of these poems have the quality of a prayer.

Grieving is painfully slow (“everyone tries to get their breath back / and never will”), as is good writing. Here, life’s threads are carefully woven in a tapestry of devotion 30 years in the making. Ultimately, it’s faith that makes you “dirt rich”, not the yachts, bathrobes or beach houses in All Too Much and Never Enough. This is a debut worth the wait.

Dirt Rich is published on 29 January. Order a copy from observershop.co.uk for £11.69. Delivery charges may apply

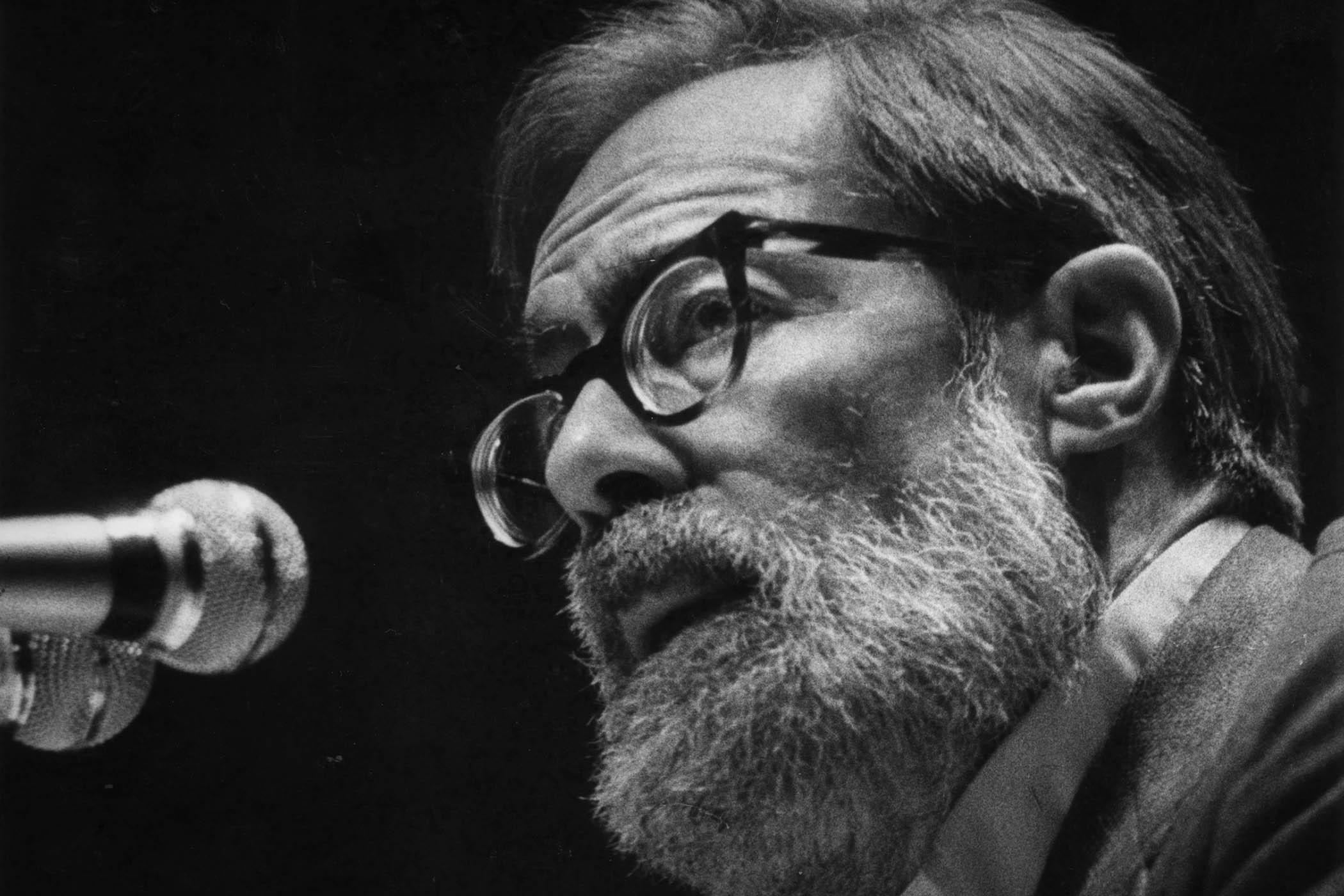

Photograph by Millennium Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy