Back in the mid-20th century, it looked as though the great clattering bus of American poetry was being driven forward by Robert Lowell, a disturbed but eloquently patrician presence at the wheel. Close behind him sat John Ashbery amid a gaggle of other New Yorkers making exciting noise, and a scattering of west coasters, all constructing their own expansive ecologies; further back, quietly staring out of the window (had she seen a moose?) was Elizabeth Bishop; and lurching up and down the central aisle was John Berryman, expostulating wildly, refusing to sit down like everyone else and do up his seatbelt.

These days the distribution of bodies has changed. Most people have promoted Bishop to the position of bus driver, Lowell has found a shady spot to think things over, the New Yorkers and others have been seated a little further apart from one another. And Berryman? He’s still prowling up and down the aisle: a genius on his best days, and on every day someone whose fabulously subtle ear has affected the course of all subsequent poetry in ways similar to (because they are derived from) those pioneered by Gerard Manley Hopkins at the end of the previous century. He is the consummate word-juggler of the “confessional” movement, and the poet who most adventurously catches the tragicomedy of modern existence.

Berryman’s “dream songs” are the climax and centre of his achievement, and their unusual publishing history is of a piece with their author’s personality. The first clutch, entitled simply 77 Dream Songs, was published in 1964 (Berryman was a slow starter: he was born in 1914, and didn’t publish his first proper book until 1948), and a further 308 followed in 1968 under the title His Toy, His Dream, His Rest. Following his death in 1972 (he killed himself by jumping off Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis, where he lived and taught), his excellent biographer John Haffenden published in 1977 a volume of uncollected poems called Henry’s Fate, which included another 45 works. Now the poet Shane McCrae has trawled once more through the archive and come up with a further 152, which brings the grand total of dream songs to 582.

McCrae introduces his selection with likable enthusiasm but leaves at least a couple of important editorial questions unanswered. Is Only Sing his title or did Berryman leave it as a note or suggestion? And what sort of order, if any, did Berryman have in mind for the poems? Given the apparent lack of manuscript dates, and the only intermittent chance to create a chronology by means of the poems’ references to real events (such as Berryman’s visit to Ireland during 1966/7, funded by a Guggenheim Fellowship), McCrae arranges the poems alphabetically according to their first lines. This is perfectly sensible – and the title is a good one, too. But as McCrae himself acknowledges, the book is “not a scholarly volume”, and Berryman’s admirers are bound to feel that its arrival strengthens the case for an expertly edited edition of the whole poem, including notes to explain its many elusive local and time-specific references, which the intervening years make increasingly obscure.

Only Sing, despite McCrae’s warm advocacy, can’t help but present itself as a volume of material found near the bottom of the barrel: if Berryman himself chose not to include these poems, and previous scholars have left them undisturbed, what hope can there be of it containing work of top quality? The question is harder to answer than it might appear. While the great majority of poets who lose their mojo slide gradually into banality or repetition, and then stay there kicking feebly (Wordsworth being the pre-eminent example), the relationship between Berryman’s strongest poems and those that have patches of rot in them, or are just thoroughly bad, is complex and unpredictable.

Berryman is the poet who most adventurously catches the tragicomedy of modern existence

Berryman is the poet who most adventurously catches the tragicomedy of modern existence

By common consent, the original 77 Dream Songs contains the finest work; it also has the most powerful element of surprise – as Berryman discovers and then masters his unique voice (a clash and reconciliation of “riot” and “prayer” in Lowell’s fine formulation). Each poem consists of 18 lines, is variously but always ingeniously rhymed, and written in language that is buckled to create a song-line at once beautiful and anguished, original and replete with echoes of the mighty dead. Also by common consent, the poems in His Toy... are much more hit and miss: some blazing masterpieces (such as the elegies for Berryman’s friend Delmore Schwartz, and the memory of his father’s own suicide in song number 145), others flat, inhibited by their merely anecdotal impulse, or – as Hopkins would have said – “Parnassian” (self-imitating) indulgence.

Only Sing contains just a handful of poems that feel fully rounded and finished: among them a beautiful, easy-talking elegy for Louis MacNeice, a surprisingly quiet-voiced poem about booze (“Waiting, just waiting, in wet heat. A little more whiskey please”), and a characteristically humorous/sad poem about desire (“She’s found arrested and with half her clothes”). And yet the relationship between these more completely successful poems and those that have something wrong with them always feels alive, as though Berryman knew that he had to keep writing the songs – even when his juices were running dry – because those that failed to reach the highest standards nevertheless created a fertile ground in which the successful ones could grow.

This is partly why Only Sing makes such compelling reading. Just when poetry – real poetry – seems to have deserted him, a line or a little cluster of lines hit the true note of what Berryman himself referred to as a “human American man”. Sometimes they’re downright comic (“The fates of our dogs / are more important than the later novels of Evelyn Waugh”); sometimes they have the disturbed pathos of self-elegy (“Pierces his mind none of them dreadfuls done / in far too often years of in & out / and up & down and over”); sometimes they achieve marvellous economies of description (“Brocades hang somehow as if they had failed the walls”); and sometimes they sing the damaged melody of his ambition:

What last point shall he thrust

up through his filthy sod to the foul live

in first, second, & high?

Small benisons won’t push, although I trust

one grand forgiving in a final strive

may break out & be I.

As these examples show, the book also clarifies still further the recurrent themes and preoccupations that give the dream songs cycle its structural integrity and drive it forward. While the sequence adopts certain strategies associated with a journal or diary (when something interesting happens to cross Berryman’s path, he writes about it), and always seems to enjoy being taken off-guard (by a new face, a new book, a new slice of scenery), its abiding preoccupations form a relative tight unit. “Women were – not art – my fate,” he says in one song in Only Sing, and just as some of its predecessors celebrated sexual longing even while mocking its follies, so here he complains of feeling “half-dead of love”, or stung by “sharp love”, or lost in “forests of desire”. Also in ways that recall previously published songs, his attraction to women proves inseparable from his other recurrent themes: mental illness (“a body back from Hell”), bodily decay, the fear of death, the appetite for death, and the self-reproach that these things stimulate. “Death, however, my live friends, is the word; / death and sex,” he says with alarming baldness in one of the few incomplete fragments that McCrae has included.

“The poetry of earth is never dead,” said John Keats, and the judgment of poets’ deserved place in the great bardic pecking order – a matter that greatly preoccupied Berryman – is never done either, and nor should it be. For a while, back in the day, it seemed that the unevenness of Berryman’s work, along with its radical distortions of familiar language, might count against him, making him seem too fidgety for his own good, and too eccentric. But while the unevenness of his work remains a thing to navigate, the fierce and beautiful oddities of his language, and the brave open-heartedness of his written response to life, are proving a form of greatness, and a source of inspiration for those who follow in his turbulent wake.

Only Sing: 152 Uncollected Dream Songs by John Berryman, edited by Shane McCrae, is published by Faber (£12.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £11.69. Delivery charges may apply

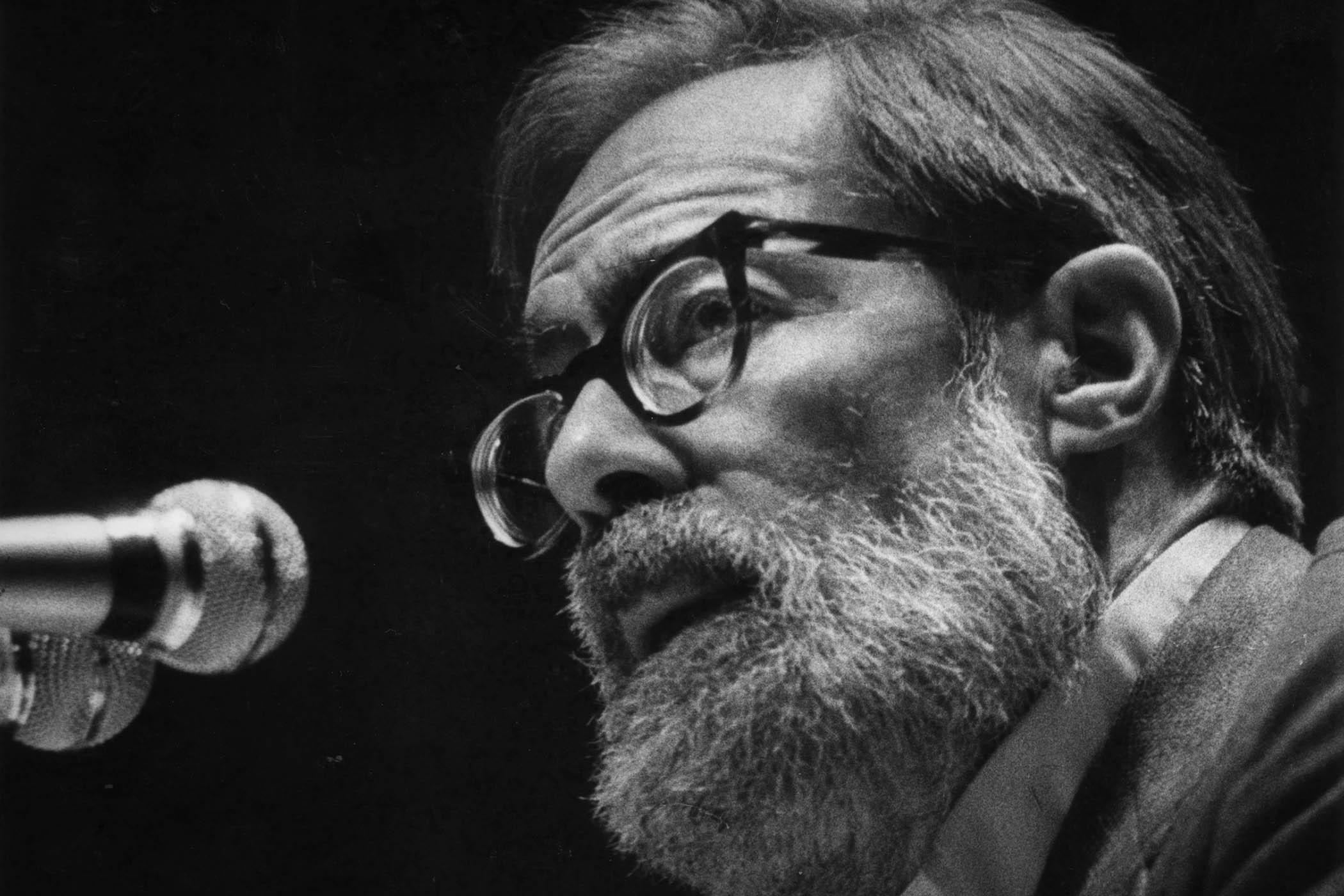

Photograph by Pete Hohn / Star Tribune via Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy