Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife

Francesca Wade

Faber, £20, pp480

What set Francesca Wade on to Gertrude Stein? Why did she decide to write a book about the writer one obituarist described – not unfairly – as “the Typhoid Mary of prose style”? In her introduction to her new biography, Wade admits that she came to her first through her legend: as a woman whose portrait was painted by Picasso; who with her brother, Leo, collected Matisse et al at a time when such artists could barely give their work away; and who shared her life with the irredeemably strange Alice B Toklas, whose “autobiography” she ventriloquised in order to make herself its principal star. Unlike many of those who knew Stein, Wade admits to liking her unabashed self-mythologising, an impulse born of her conviction that her genius far exceeded that of her contemporaries, James Joyce and TS Eliot.

However, there was something else, too. In 2019, Wade visited the Beinecke Library at Yale University, where Stein’s voluminous archive resides, and there she became the first researcher to look at the papers of Leon Katz. Out in the world, Katz’s name is unknown. But in the weird realm that is Steinland, he’s a key figure. Having come upon some of Stein’s early notebooks as a doctoral student, in the early 50s Katz somehow persuaded Toklas to spend four months helping him untangle their scribbled contents – an unprecedented coup (Toklas was a gatekeeper like no other, as obstructive as a cobra). The material he gathered was supposedly revelatory, but he never published, choosing instead to hoard it. Even wily Janet Malcolm couldn’t make him spill, a story she recounts in Two Lives, her own compelling book about Stein and Toklas. Katz’s papers only became available to readers after his death in 2017, when they joined Stein’s at the Beinecke.

Access to them seemingly gave Wade the idea for her book’s structure, which comprises two parts. The first is a straightforward biography of Stein, a tale that begins in Oakland, California, where she grew up the youngest of five children of a Jewish businessman, and ends in Paris, where she died of cancer aged 72, her celebrity by then considerable, but her reputation as a writer mostly in the mud. The second is devoted to what Wade calls her afterlife, an account that embraces not only the efforts of scholars and biographers to pin her to the page, but which also recounts the last years of her devoted companion, Toklas, whom Stein had instructed to get all her books posthumously into print – a task that was unlikely to prove easy. In her lifetime, the work of her own that Stein took most seriously was that which publishers inevitably most fiercely disdained. Only The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas (1933) was anything like a real success – which was a grand irony. As Wade writes, its readability (“as clear as comic strip”, cheered Newsweek) rendered it the most un-Steinish book she’d ever written. Many critics – though not her friend Ernest Hemingway, who thought it “pitiful” – read it with more of a sense of relief than admiration.

Wade has clearly laboured over this bifold form, and the result is a feat; I admire it much more than her first book, Square Haunting, about five women writers who lived in the same London square. Deeply researched and elegantly written, it is born of good, feminist instincts – a determination, perhaps, to see beyond cliches – and it comes with a certain glamour, thanks to its cast. Stein collected famous friends as assiduously as she did art. Those with star cameos include not only Picasso and Matisse, but also Guillaume Apollinaire, Thornton Wilder and Pierre Balmain.

Ultimately, Katz’s insights may not be as exciting as billed, but they do suggest that Toklas’s devoted long service was perhaps more complex – more sadomasochistic – than we knew. “Sometimes I look at that machine and hate every key on it,” she said to him of the typewriter on which she’d banged out every word Stein ever wrote.

And yet I cannot say that I really enjoyed this book. Wade takes Stein seriously at all times, and this is silly. She may not have been an out-and-out charlatan, even if her sandals and corduroy get-ups are suggestive of a certain kind of intellectual grift. But when Wade refers sombrely to Stein’s “writing practice”, it’s hard not to laugh. Surely she was making it up as she went along! As she said herself: “I write to write.” Her apparent desire to shed language of all its associations so her own words mean something entirely new is batty as well as egomaniacal, mere gibberish next to her rival, Eliot (“Why is a feel oyster an egg stir?”).

In the end, for all Wade’s determination, you find yourself with Virginia Woolf, whom she tried to persuade to publish her modernist saga, The Making of Americans, under the auspices of the Hogarth Press. “We are lying crushed under a great manuscript of Gertrude Stein’s,” Woolf wrote to a friend. “I cannot brisk myself up to deal with it.”

Order Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife at observershop.co.uk for a special 20% launch offer. Delivery charges may apply

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

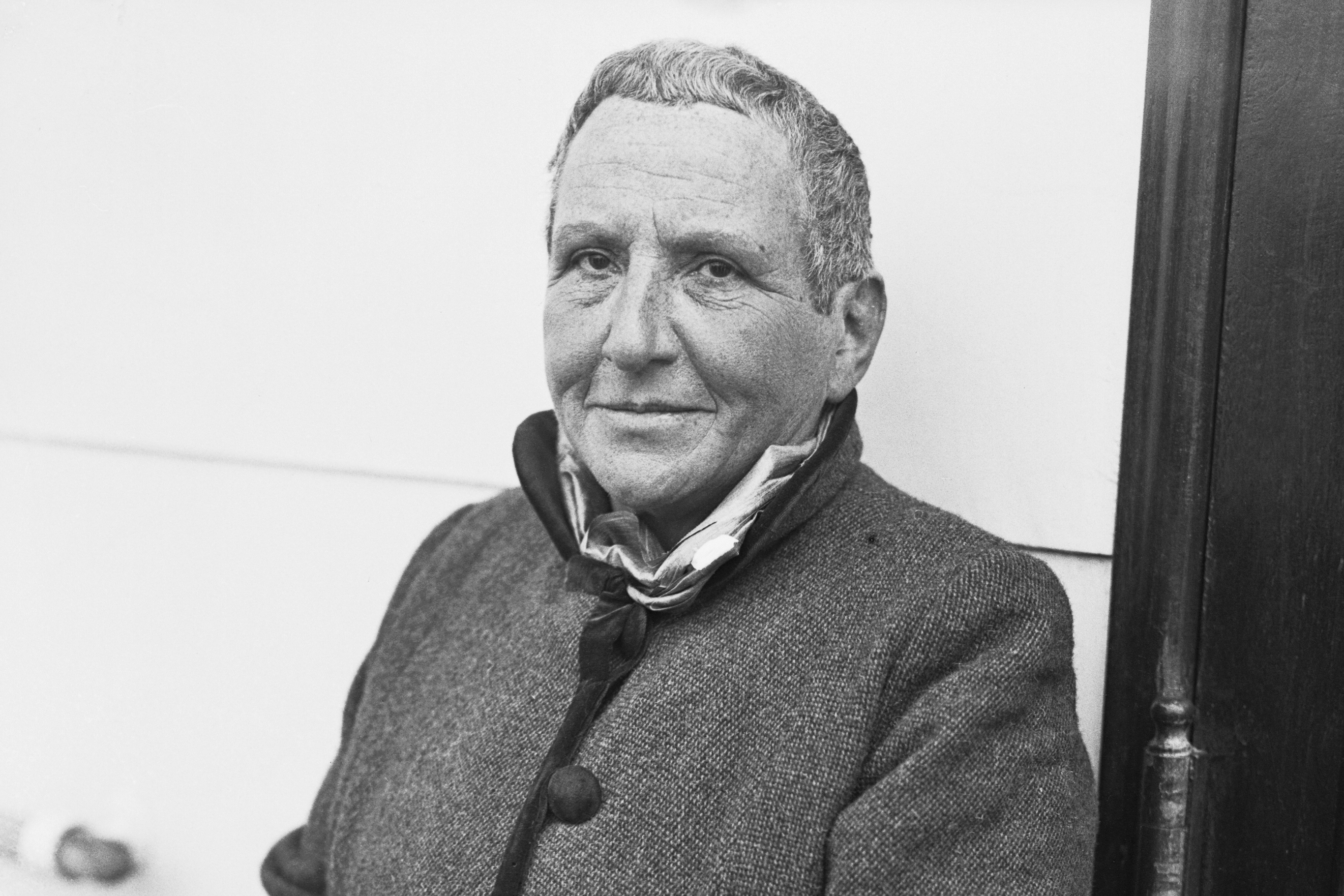

Photographs by Bettmann Archive/Getty