Since this century began, Elizabeth Kolbert has been a necessary voice on the environment. She has been a staff writer on the New Yorker since 1999, and her 2014 book The Sixth Extinction won the Pulitzer prize for general nonfiction. The present volume, Life on a Little-Known Planet, is a compendium of some 16 of her New Yorker essays, each with a short note to bring it up to date. Though energetic and hugely informative, these are rarely optimistic. On climate matters, the essays often report the stalling, greed and downright suppression of truth that will appal future generations. In her 2015 piece The Siege of Miami, she reports that Florida’s then governor Rick Scott, a Republican, “had tried to ban talk of sea-level rise”. In the island city of Miami Beach, streets are regularly submerged by salt water issuing from storm drains, but “state employees were supposed to speak only of ‘nuisance flooding’”. Geologists in Florida predict this “nuisance flooding” means “much of the region may have less than half a century to go”.

Elsewhere, as some are fretting about AI and its implications, others are wondering about whale-speak. Talk to Me, the opening essay, published in 2023, is subtitled: “Can artificial intelligence allow us to speak to other species?” Given enough human words and sentences to train upon, large language model AI can predict what words come next. Sperm whales communicate with clicks that occur in patterned units called codas. “Even by human standards,” Kolbert writes, “sperm whale chatter is insistent and repetitive.” The theory is that if one could record enough of these whale exchanges, a ChatGPT-type program might eventually amass sufficient data to predict whale talk, albeit without understanding. Because there are no whale libraries to plunder, live recordings must be done at sea. A team is working in the waters off Dominica to do just that. “Trying to attach a recording device to a sperm whale is like trying to joust while racing on a jetski,” Kolbert points out. And then, as one of the team says, “the next step would be to push beyond prediction and into comprehension”.

Above: ‘nuisance flooding’ or further evidence of our climate emergency? A residential area in Florida following Hurricane Ian, 2022; main picture: a sperm whale shepherds her calves.

It would be revolutionary, but can we wait that long? If we wanted to speak with other species, we’d have to make sure they survived. One day, out on a sperm whale recording mission, the team witnessed a bloom of blood on the water. It was not an attack as first supposed, but the birth of a calf. Almost immediately, a pod of pilot whales – which are predators – arrived, then a pod of Fraser’s dolphins. As the biologists on their boat witnessed this extraordinary melee, and noted that no violence seemed to be taking place, a different theory began to arise. Perhaps the pilot whales were not on the hunt after all – perhaps they and the dolphins were actually milling around to protect the newborn calf. But from what? Sharks, attracted by the blood. Perhaps it was a mammalian evolutionary adaptation. But one sadly unnecessary. Sharks would have been much more numerous in the past, before humans began killing them off in huge numbers. And what would the whales say to that? What would the sharks?

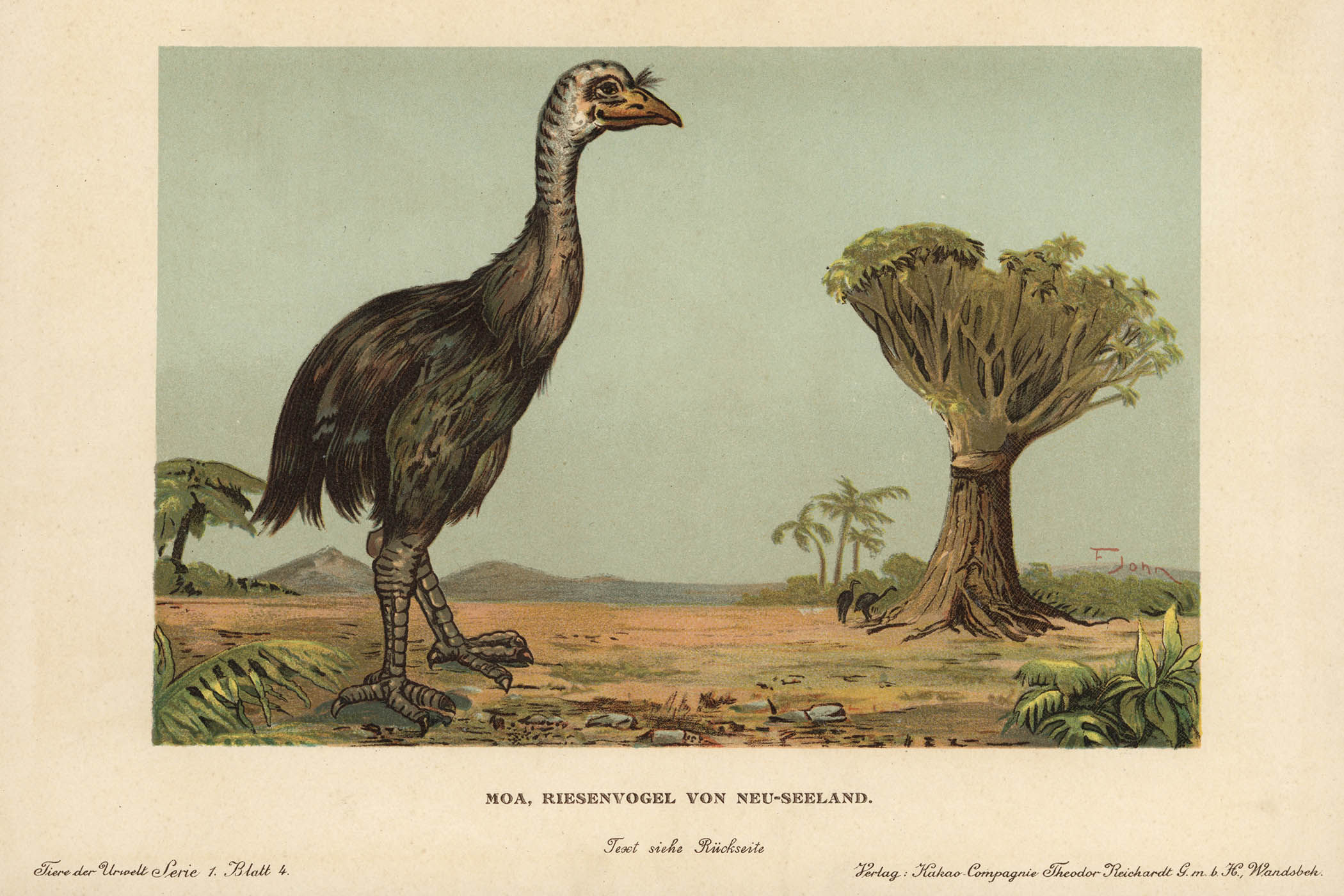

While, in one part of the world, humans are striving to talk to mammals, in another, the project is to eradicate them. In Killing Mrs Tiggy-Winkle, Kolbert travels to New Zealand to describe that country’s collective effort to rid itself of its huge numbers of invasive predators. Aside from two species of bat, the New Zealand archipelago has no native land mammals. Instead it developed its own birdlife, which is now in dire straits. The moa are already gone: 12ft tall and flightless, they were consumed by the first Maori settlers, who also unwittingly brought rats. It took Europeans to deliberately introduce the possums, stoats, ferrets and, yes, hedgehogs, which are presently feasting their way through the remaining native birdlife. But the attitude has turned. Intense trapping and aerial poisoning programmes aim to have NZ predator-free by 2050, perhaps in time to save the kakapo, a nocturnal flightless parrot now critically endangered, and even the kiwi itself. It’s a tall order, but the public is involved – even schoolchildren – in a community-level, nation-building effort. In fact, species eradication has become one of New Zealand’s exports (as well as wool spun partly from possum fur). It’s well known that if you want to rid your town of rats, or more likely your island, hire New Zealanders.

It ought to be frightening – and it is – but we keep reading. Kolbert’s writing is serious but adroit, with just enough wry humour

It ought to be frightening – and it is – but we keep reading. Kolbert’s writing is serious but adroit, with just enough wry humour

However, there is little point in saving species, never mind speaking with them, if their habitats are unusable. Again and inevitably, Kolbert’s work circles back to CO2 emissions, which have now reached a record 425 parts per million. How are we to prevent unconscionable degrees of warming, and catastrophic “nuisance flooding”, given the lack of will to reduce emissions? Her fascinating essay Going Negative is about the efforts to develop technologies that would pull carbon from the atmosphere, known as direct air capture. At her time of writing, 2017, such technologies were underdeveloped. They had become “vital without being viable”. Vital, because the computer models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) rely on such technologies to keep atmospheric CO2 at sub-disaster levels. As Kolbert says, the attitude is: “There has to be an answer out there somewhere, since the contrary is too horrible to contemplate.”

Kolbert visits some researchers who are attempting to develop direct air capture. (One wonders why there isn’t a state effort on the scale of the Manhattan project.) But having captured the carbon, what is to be done with it? Theoretically, carbon capture machines could be installed anywhere: they could be as suddenly ubiquitous as the iPhone. It is an enormous wager. As she writes: “Depending on how you look at things, the technology represents either the ultimate insurance policy or the ultimate moral hazard.”

The giant moa bird, once native to New Zealand but now extinct.

So we go on. It all ought to be frightening – and it is – but we keep reading. Kolbert’s writing is serious but adroit, even sassy: there is just enough wry humour. The necessity of fitting huge subjects into 20 clear pages suits her style. Each essay is pacy, with energising turns, and each belies the amount of research required, by phone, Zoom, email and a considerable amount of actual travel. Especially interesting are the people she engages with, whom she is careful to acknowledge. At species level, we seem clueless at times: we elect appalling figures to high office, or carelessly allow them to assume power and vast wealth; our statesmen and women fail us at every turn. But also, as individuals, we can be brilliant, visionary, eccentric, committed. Each of Kolbert’s essays is populated with such figures, mostly but not all scientists. (One essay concerns an island community of self-styled “normal people” in Denmark who simply decided to eliminate their use of fossil fuels.)

Kolbert is adept at seeking out these people. She devotes one essay entirely to Christiana Figueres, the Costa Rican who was one of the architects of the 2016 Paris Agreement; another is dedicated to conservation biologist Sam Wasser, who uses DNA to fight elephant poaching. Aside from her dexterity as a writer, it is the presence everywhere in her work of such people that leaves readers with a feeling not of hopelessness but of brinkmanship. What will happen over the next 50 years or the next 100 years? As Figureres herself said: “It’s actually very exciting … to be alive right now!”

Related articles:

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert is published by Bodley Head (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50 Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photography by Mike Korostelev/Getty Images, Universal Images Group