This is now the 10th year I’ve been writing this look-ahead, and the first where my fiction column hasn’t been twinned with the nonfiction of the late and greatly missed Rachel Cooke (Erica Wagner has taken up the mantle, overleaf).

One thing that always strikes me is the way that fiction seems to surface the repressed and unsaid of the moment. With that in mind, and having read dozens of novels over the past six weeks, I can say that our collective subconscious is chewing over several themes. The first is the legacy of Covid: how we memorialise something that the culture has been so eager to forget, and how we mourn the dead and appease their ghosts. Then there’s war: Israel-Palestine, certainly, but also other episodes of historical violence. Finally, there’s the political moment: polarisation, the place of technology within our lives and the looming climate crisis.

Here are the books to look out for this year (with first novels left to The Observer’s annual debut-fiction feature, published later this month).

January brings Ali Smith’s Glyph (Hamish Hamilton). Two estranged sisters are reunited when a book – in a typically Smithian move, her own previous novel, the dystopian Gliff – reawakens “glyph”, the childhood “spirit game” they invented to survive their mother’s death and their father’s brutality; a playful, melancholy story of sibling bonds, unreliable memory and the tales we use to keep the dead close. It’s also a powerful anti-war novel, with Palestine firmly in its sights.

Vigil (Bloomsbury) – the second novel by Booker winner George Saunders, the American master of the short story – follows Jill “Doll” Blaine, part angel, part ghost, as she shepherds the dying into the next world; her latest charge is KJ Boone, a climate-denying oil tycoon whose life’s work has helped conjure a planet of lethal weather. A chorus of the dead clamours for justice as Jill wrestles with what mercy may still mean for such a fallen man.

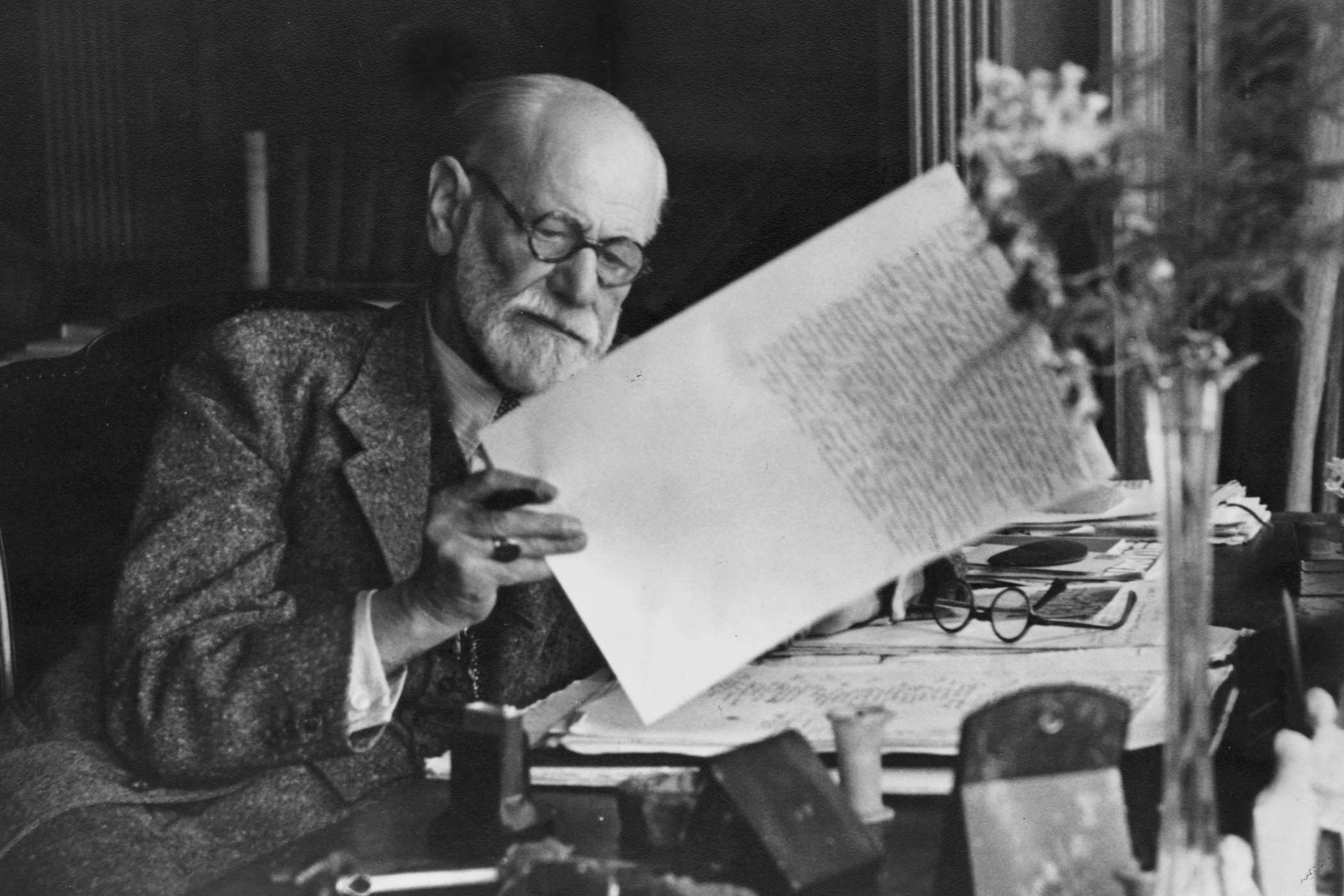

At the start of Departure(s) (Jonathan Cape), Julian Barnes announces: “This will be my last book.” Is it fiction? Is it memoir? On the occasion of his 80th birthday, reckoning with the blood disorder he’s lived with since 2020, he delivers a playful, profound meditation on memory and the writer’s endgame.

There’s a story – or a story within the story – about two university friends whose 40-year relationship Barnes narrates, breaking his promise never to write about them. But, really, it’s about what remains when time runs out: unreliable memories, lost opportunities, the gap between what we remember and what happened. Metafictional, moving, unmistakably Barnes.

In February, James Meek’s Your Life Without Me (Canongate) sees Mr Burman, a widowed teacher estranged from his daughter, summoned to London after his former pupil Raf commits a spectacular act of terrorism. Unsettling and boasting a haunting twist, this is one of our great prose writers on guilt, complicity and forgiveness.

Francis Spufford’s Nonesuch (Faber) returns to the wartime London of his superb Light Perpetual for a very different counterfactual tale. Spufford has written about how children’s books shape adult minds, and here he gives us those pleasures – secret worlds, impossible quests, magic – in their most sophisticated form. Iris Hawkins, a working-class girl in a City brokerage, navigates 1939 London, where the occult and ordinary occupy the same space. She conjures stone giants, crosses bridges through twisted time and races a fascist to safeguard history itself. It’s His Dark Materials meets the blitz: the deep satisfactions of children’s literature reclaimed for adults who still want stories in which the world is wondrous.

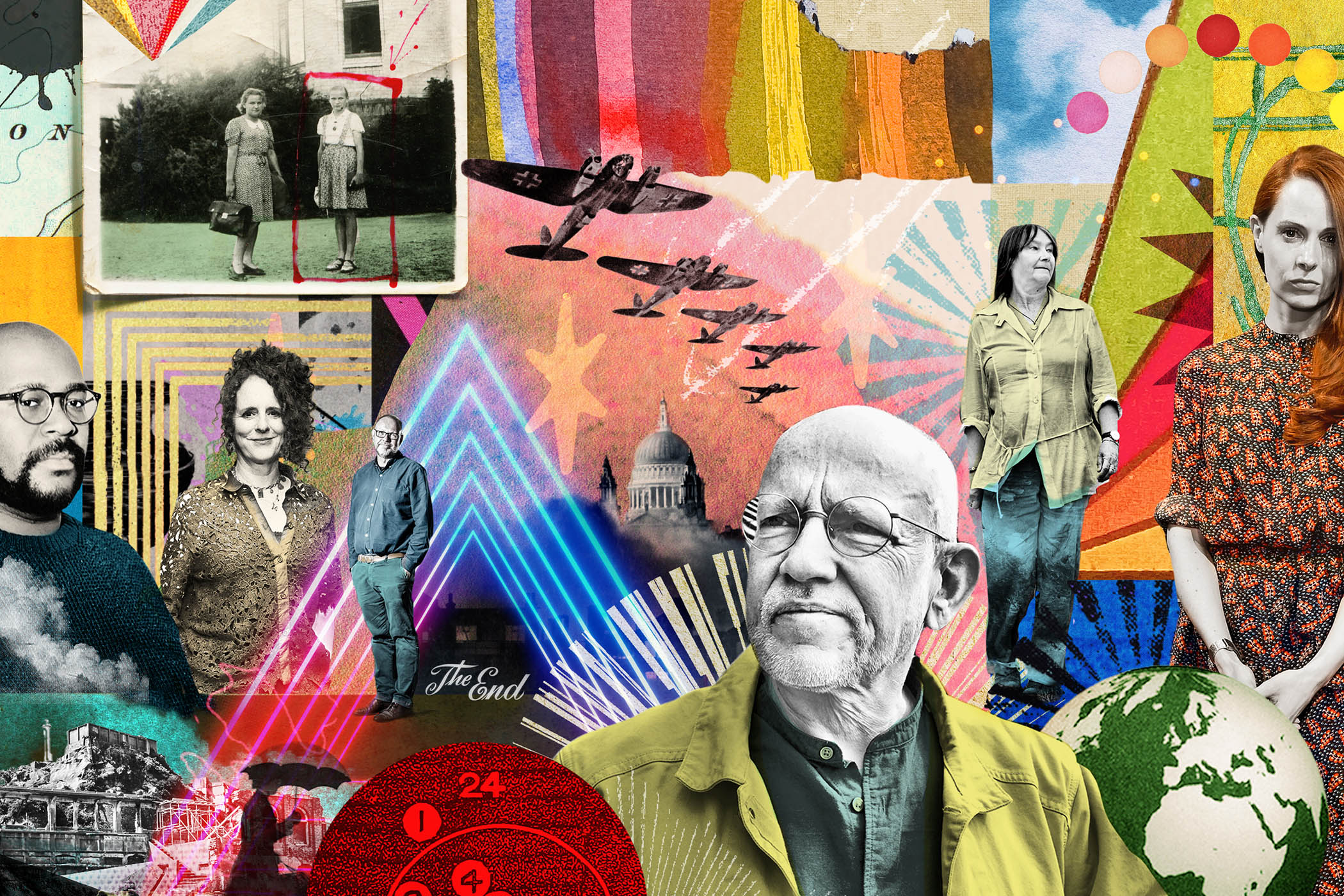

From left, Brandon Taylor, Maggie O’Farrell, Francis Spufford, James Meek, Ali Smith and Gwendoline Riley

Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s Almost Life (Picador) arrives in March. Her third adult novel traces the decades-long love story between Erica, an English tourist, and Laure, the Parisian she meets on the Sacré-Cœur steps in 1978. It’s a beautifully written exploration of desire, freedom and the roads we do and don’t take. John Lanchester’s Look What You Made Me Do (Faber) is an absolute riot. It’s both a black comedy of revenge and entitlement, and a complex portrait of millennial/boomer conflict. When Kate recognises intimate details of her marriage in a hit TV series written by younger screenwriter Phoebe, an intergenerational battle over blame and ownership begins: sharp, queasy, totally compulsive.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In Brandon Taylor’s stunning third novel, Minor Black Figures (Jonathan Cape), Wyeth, a young Black painter, falls for Keating, a doubting priest, in a sweltering post-Covid New York. Taylor writes magnificently about art in a Künstlerroman that doubles as an inquiry into desire, faith and what it costs to create beauty in a world that would rather not see you.

April has Yann Martel’s Son of Nobody (Canongate), the first novel in a decade from the author of Life of Pi. A fictional Homeric epic about an overlooked Trojan hero is interspersed with footnotes from failing academic Harlow Donne, who translates the poem for the daughter he has left behind. Published the same month is The Palm House by Gwendoline Riley, one of our finest novelists of constrained fury: nobody writes better about the emotional labour of enduring difficult men. When Edmund Putnam leaves Sequence magazine after 25 years, driven out by a new editor, he performs his humiliation with operatic self-pity. But this is really the narrator’s story: her exhausting friendship with Edmund; his demands, self-absorption, and the way he treats kindness as prey. Riley’s prose is sharp, her dialogue pitch-perfect, her exasperation channelled into devastating comedy.

Ben Lerner’s intricate novels are always about more than their surface subject. In Transcription (Granta), an unnamed author travels to interview Thomas, his 90-year-old mentor in the still-masked post-Covid days. He drops his phone in the sink and is both left without a device to record the interview and stranded in a world in which the phone is a universal key. Later, in the wake of Thomas’s death, he gives a speech at a conference in Spain. Then, in a section that is in complex dialogue with the opening of the book, we meet Max, Thomas’s son. It’s a short, smart novel about parenthood and influence; about how much of our lives we have ceded to the black rectangles in our pockets.

Writers are grappling with the political moment: polarisation, technology, the climate crisis

Writers are grappling with the political moment: polarisation, technology, the climate crisis

May is ushered in by the great British nature writer and novelist Melissa Harrison. The Given World (Hutchinson Heinemann) is a dark pastoral set in the Welm Valley, where the river misbehaves and villagers share a recurring, uncanny dream. Through multiple voices, Harrison conjures a community sensing that something has shifted, writing about the English countryside and its people with her customary distilled intensity in a book about change and belonging in an apparently unchanged landscape.

John of John (Picador) by Douglas Stuart sees John, AKA Cal, return broke from art school to the family croft on the Hebridean Isle of Harris. Trapped between his father, John – sheep farmer and Presbyterian pillar – and his profanity-loving Glaswegian grandmother, Ella, Cal hides his sexuality while John Snr prays he will be saved. This is a tender yet fierce story of fathers and sons, secrets and silence, from the author of Shuggie Bain.

Erica Wagner of this parish has a novel out in May; the luminous Wash (Salt Publishing) reimagines the life of Washington Roebling, who oversaw the building of the Brooklyn Bridge while bedridden and in crushing pain with the bends. What’s special about this book is the magical way that Wagner summons the past and, in particular, the characters around Wash: his formidable wife, Emily, his brutal father, his friendships and rivals. A memorable work of historical fiction.

June sees Tahmima Anam’s Uprising (Canongate), inspired by the sex workers of Banishanta in Bangladesh. On this desolate, sinking brothel island, children watch their mothers suffer cruelty and servitude under Amma, the sadistic madam. Then Kusum Khan washes ashore and refuses to yield, transforming the mood of resigned acceptance into defiance in an urgent, collective-voice novel. It’s vastly different from, and more experimental than, her previous novel, The Startup Wife. I loved it.

Also in June comes Maggie O’Farrell’s Land (Tinder Press), a sweepingly ambitious novel from the author of Hamnet. On a windswept Irish peninsula in 1865, Tomás makes maps for the Ordnance Survey in the wake of the great hunger, aware he’s recording a catastrophe. An unmapped woodland sets him off on a quest that echoes through the lives of his descendants.

In July, we have Charles Cumming’s Icarus 17 (Hemlock), the fourth in his Box 88 series – and the best yet. If there was any question as to who is the rightful inheritor of John le Carré’s crown as the king of elegant spy fiction, this proves that it’s Cumming beyond any doubt. A thriller about ageing, guilt and the long shadow of past choices, it opens with the Jamal Khashoggi murder, then hurtles to Sweden, where a gunman targets hero Lachlan Kite’s family in Djursholm; meanwhile, the intelligence agent’s ex-girlfriend Martha resurfaces after 20 years, desperate to find her son who has gone missing in Greece.

September delivers two Sebastians. The 17th novel by Sebastian Faulks, Farewell to Eden (Hutchinson Heinemann), introduces Philip Deval, who arrives at Witchelm House girls’ boarding school in 1951 with forged references, fleeing a past that involves a woman called Alice, a monastery in Palestine and the last chaotic years of the British mandate. A dual narrative twines a tender love story with a devastating historical strand haunted by grief and the impossibility of starting again.

Sebastian Barry’s The Newer World (Faber) reunites us with Thomas McNulty and John Cole from Days Without End, only this time seeing 19th-century America through the eyes of Tennyson Bouguereau, mixed-race son of a creole blacksmith hanged while trying to buy Tennyson’s enslaved mother’s freedom. From Tennyson’s childhood in 1840s Tennessee through the civil war and Wounded Knee to a desperate trek towards Alaska’s goldfields, Barry records a life between worlds, in tender, elegiac prose. This is the novelist at his best: a masterly work of historical witness and moral reckoning.

I try only to include books I’ve actually read in this look-ahead, but I’ll make an exception for the great William Boyd’s Cold Sunset (Viking). I’ve loved his novels about Gabriel Dax, the reluctant spy, and this third outing sends Dax to cold war Moscow to deliver a drawing to the Kim Philby-ish defector Kit Caldwell. Boyd does shadowy worlds and moral complexity better than anyone. I can’t wait.

To browse all books included in What to read in 2026, visit observershop.co.uk. Delivery charges may apply.