Trying to explain his taste for writing “problem” stories built around a pressing moral dilemma (“Will he or won’t he do the right thing?”), George Saunders once pointed an interviewer to the impact of his Catholic upbringing: “That beautiful heroic narrative of Christ sacrificing himself to save everybody, even when he didn’t want to” taught him that existence was “painful and that the purpose of an individual life was to aid other beings in trouble, which runs counter to our instinct, which is protect our own ass”.

That friction drives all of Saunders’ work. He first made his name with cartoonishly satirical American dystopias narrated by ordinary Joes struggling to do the right thing, as in the title story of his 1996 debut CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, about a put-upon employee at an ailing theme park. In The Semplica Girl Diaries, from the collection Tenth of December (2013), a striving family man frets that he’s unable to give his daughters the lifestyle enjoyed by his better-off neighbours, who are in thrall to a craze for importing poor young women from abroad to hang decoratively in their back gardens.

A nightmarish allegory of globalised consumerism, the story is all the more effective for initially seeming to misidentify which of its characters most requires our sympathy. At his best, Saunders enacts a moral awakening in real time: his Booker-winning novel Lincoln in the Bardo, a historical ghost story woven around the death of Abraham Lincoln’s 11-year-old son from typhoid, uses its distressing evocation of private grief as a way to explore the contemporary horror of slavery.

The possibility of an epiphany sparked by communication from beyond the grave is also at the heart of his tender new novel, Vigil, set in present-day Dallas and narrated by the soul of a young woman mistakenly blown up by a car bomb. The dilemma this time concerns global warming, and the person who has to do the right thing is KJ Boone, an elderly, cancer-riddled oil executive plagued on his deathbed by a host of apparitions – endangered wildlife, old classmates, a villager from climate-ravaged Rajasthan – each beseeching him to repent his life’s work while greedy lobbyists urge him not to. These visitations are overseen by the undead protagonist, Jill, who has plummeted to earth in order to ease Boone’s own transition to the afterlife, together with another long-passed spirit – “the Frenchman” – who is gnawed by regret at his invention of the combustion engine. “It poisons, madame... I did not know it then. But I know it now. I have been corrected. As he must be.”

Intrigue thrums everywhere you look, not least the mystery of why Jill was parted from her beloved husband, Lloyd, a cop in Indiana, to say nothing of her shock at how he lived out his widowhood. But the main focus is the testy dialogue between Jill and Boone, on whose internal psychodrama the novel’s ethical and emotional clout depends. Although now spectacularly wealthy, Boone lifted himself out of impoverished youth in Wyoming, and resents what he sees as carping from enemies of progress: “People forgot the empty larder. Forgot drought, forgot famine.” (And doesn’t everyone rely on oil? “You drove, you flew, you kombucha-making hypocrite,” he thinks, when confronted by one especially righteous critic.) Set against this reasonable argument is his tendency to lapse into boorish, politically partisan spite – but also a genuine fear of hearing too much about changes in the weather, particularly from overseas.

The novel’s drama ultimately pivots on just how much Boone knew or didn’t know when delivering an influential speech that claimed the jury was still out on the reality of climate change. Saunders keeps preachiness at bay by making sure never to lose sight of the abiding agony of an 87-year-old man dying in pain. There’s also our ever-present delight in getting to grips with the enjoyably knobbly mechanics of the novel’s spectral milieu. Saunders doesn’t gloss his terminology: Jill, who refuses the term “ghost”, referring only to “our ilk” – you never know exactly what she is – communicates with Boone via “the mind-sample delivered by my forearm-immersion”. Her estrangement from earthly life is expressed in part as a relationship to language, seemingly no longer quite hers to use: “I myself, I recalled, had, in that previous realm, driven several ‘autos’, the first of which had been ‘Chevelle’. ‘Chevelle’, packed with ‘girlfriends’, as well as my cousin, ‘Steve’, would be positioned so as to face a ‘movie-film’...”

Saunders keeps preachiness at bay by never losing sight of the abiding agony of an 87-year-old man dying in pain

Saunders keeps preachiness at bay by never losing sight of the abiding agony of an 87-year-old man dying in pain

While there’s a willed laboriousness to all this (“I emitted the shrill repetitive shrieking one of our ilk will emit if wishing to attract others of our ilk for consultation”), the reader happily accepts it as the price of portraying a world beyond ordinary perception. It helps, too, that Saunders always sees the funny side of his setup: his undead josh one another about being “entirely transparent”, and there are regular outbreaks of physical comedy based on Jill’s phantasmal interaction with the real world. Saunders’ paradoxically naturalist supernaturalism – in which his past life as a geophysical engineer seems at least as influential as his conversion in adulthood to Buddhism – feels apt in a novel that rather brilliantly uses its otherworldly plot to argue for the importance of listening to science.

Yet these are deep waters to cross in barely 200 pages, and Vigil’s peace-making reflexes in the face of contentious issues can lead the book into hazy sentimentality. Besides Boone, Jill enters the mind of her inadvertent killer – a lowly, lonely crook named Paul Bowman, born, we’re told, with “limited intelligence, crude features, an almost nonexistent sense of curiosity”. The novel asks us to consider how much circumstances dictate actions. “At what precise moment could Paul Bowman have become other-than-Paul Bowman?” Jill wonders.

Caught between empathy and determinism, such moments are queasy, even sinister, and our unease is hardly assuaged by the sense that the narrator – a paragon of understanding – might stand in for Saunders’ conception of the writer’s task. Vigil’s microscopic attention to physics strikes us partly as a way for Saunders to work out his long-held scepticism about omniscient narration (Boone’s consciousness is relayed to us only via Jill’s entering “the orb of his thoughts”).

But Saunders’ deployment of the supernatural also seems a vehicle for wider consideration of the ways and means of fiction – not least in the current political moment, which is liable to assail any writer with self-doubt. Jill can’t change Boone, still less the planet, but she can at least offer consolation, a gift courtesy of her dematerialised state. Lamenting her prior “limited view, her nominal ability to comprehend, her constrained love”, she thinks: “No: this, this now, was me: vast, unlimited in the range and delicacy of my voice, unrestrained in love, rapid in apprehension, skilful in motion, capable, equally, of traversing, within a few seconds’ time, a mile or 10,000 miles.”

Disembodied, able to enter the lives of others through concentrated application of a superpower gained through self-sacrifice... now who does that sound like? So entertaining on the page, Vigil’s bravura dramatisation of the capacities and limits of sympathy also leaves you wondering about its motivations – and what separates the craft of fiction from a God complex.

Vigil by George Saunders is published by Bloomsbury (£18.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £17.09. Delivery charges may apply

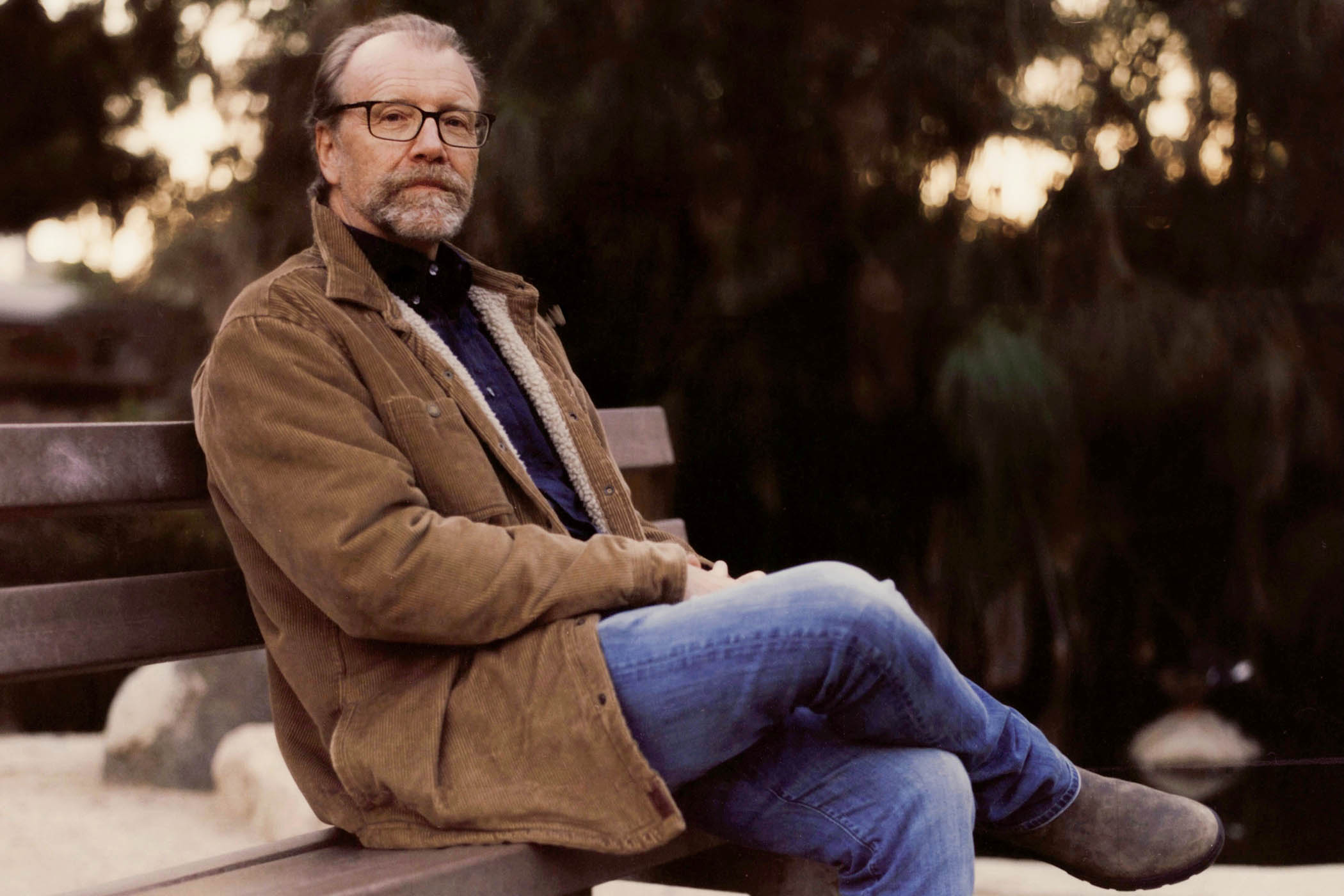

Photograph by Pat Martin

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy